The First-Rung Collapse: How AI Career Displacement Will Reshape Lifetimes and Education

Published

Modified

AI is eroding the first rung of professional careers Upward mobility is weakening as entry-level roles disappear Education and policy must rebuild structured career pathways

By 2030, tens of millions of early-career roles that once taught judgment, responsibility, and craft could vanish or be radically redefined — and with them, the ordinary pathway that turned young workers into mid-career professionals. This is not merely speculation: companies are already automating the “first rung” tasks that allow graduates to learn on the job, and entire cohorts are reporting far fewer entry-level openings. The result will be more than temporary unemployment. It will be a rerouting of whole career trajectories and life plans: what students choose to study, when they leave home, whether they can afford housing, when they start families, and how social mobility functions across generations. If policymakers and educators treat automation as a one-off productivity story, they will miss how technology is bending lifetimes. We must reframe the question from “how many jobs will be lost” to “how will careers be forged — or fail to form — across a life?”

AI career displacement and the reframing we need

This isn't just about people being out of work for a short time. It's about how people plan their whole lives. It will affect what students decide to study, when they leave home, whether they can afford to live, when they start a family, and how easy it is for people to move up in society. If those who make the rules and teachers see automation as just a way to make things more efficient, they'll miss the bigger picture. Technology is changing people's lives. We need to stop asking How many jobs will disappear? and start asking How will people start their careers, or not be able to start them at all?

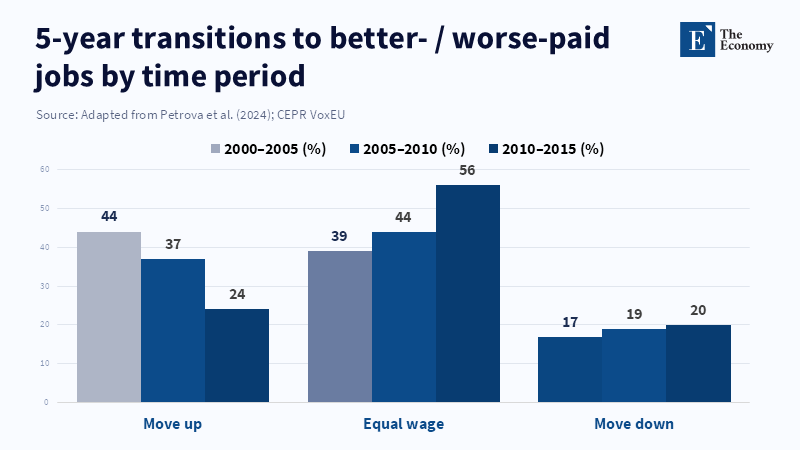

The main thing to understand is a change in how we think. Most discussions focus on numbers: how many jobs are lost, how many tasks are different. This way of thinking sees labor as just a resource. But thinking about a person's whole life means seeing labor as a journey. When the first step of a career is missing, it impacts everything that follows. Learning on the job early in a career helps people develop skills that can't be learned in a classroom. These skills are important for promotions, sound judgment as a manager, and confidence in your job. If entry-level jobs are replaced by machines, fewer people will ever get to those middle-level positions. This could create a situation where some people do really well, while others are left behind in terms of money, experience, skills, and life stability.

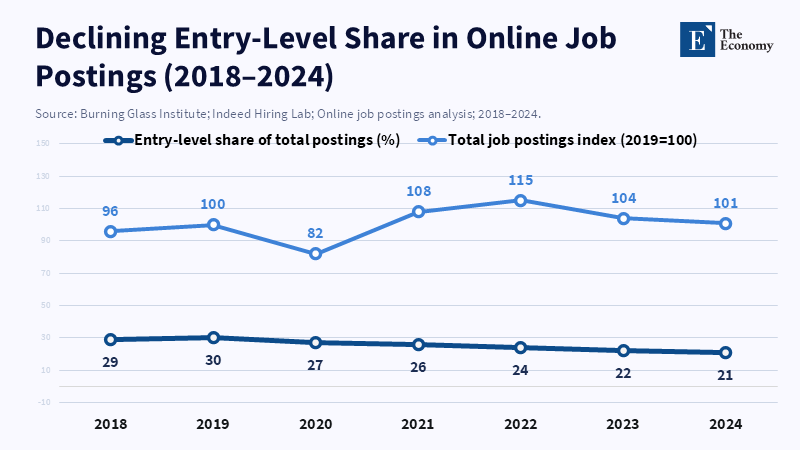

There's already evidence of fewer entry-level jobs. Recent reports from the engineering field show that new graduates are finding fewer internships and junior positions. This is because computers can now handle routine tasks such as identifying problems, maintaining records, and performing basic coding. Companies now seek new employees with better judgment and an understanding of complex systems. This makes it more difficult for people to be hired. According to a recent OECD report, more than half of companies in high-income countries still provide some form of training for their employees, indicating that although access to early-career training varies, it remains a widespread practice.

If early learning opportunities disappear, it affects every stage of a person's career. A young worker who doesn't get to learn basic tasks will have a weaker resume and less guidance. This makes it harder to get promoted, which means lower earnings, less money saved for retirement, and fewer assets. The usual path of college, then job, then family starts to break down. A degree without a good internship can leave some people with more credentials than they need, while others end up with no opportunities. This leads to predictable social problems, such as people starting families later, fewer people buying homes, and an even bigger gap between the rich and the poor. To fix this, we need to protect and rebuild those entry-level opportunities, not just retrain people at the last minute.

The education system isn't keeping up, and here's what we need to change:

Universities and training programs are reacting differently. Some are changing their courses to concentrate on more complex thinking skills. However, others are maintaining traditional methods of teaching. Just adding more technical skills isn't enough. The major issue is that early-career learning typically occurs in the real world. Companies used to transition new graduates into professionals through on-the-job training, such as apprenticeships. As companies use machines to handle routine entry-level work, they need to find new ways to recreate those learning experiences, or they'll end up with a less skilled workforce.

We're already seeing students change their behavior. Reports from 2024-2025 show that some students are choosing vocational trades and practical skills that are harder to automate. Others are focusing on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) skills and computer literacy as a contingency plan. This split could harm the liberal arts and other fields in which students rely on on-the-job learning to secure employment. Schools that promise the same results as before are seeing fewer students enroll in programs that don't lead to good jobs.

Practical changes are needed in three interconnected areas. First, include practical experience and supervised practice in degree programs. This way, students can develop good judgment before they start working. Second, require partnerships between schools and companies to create paid, structured early-career jobs with coaching. These shouldn't be unpaid internships. Third, measure success by how people progress in their careers over time, not just by where they get a job right after graduation. These changes require funding as well as regulatory adjustments. Governments can use matching grants, tax breaks, or preferential treatment for companies that offer these early-career opportunities. It's vital to act quickly, as the job market won't resolve this problem fast enough for everyone.

Some might resist these ideas. Companies will say that automated training is cheaper. Colleges will say that adding more hands-on training costs money. The cost of not having good career opportunities is real and affects generations. If we don't address this, we'll see more high-paying, high-skill jobs for a few, and more unstable, dead-end jobs for many. Government policies must encourage companies to rebuild these early-career opportunities, because the market won't do it in time.

How career problems affect important life decisions

The trouble in people's careers isn't just about economics; it changes how they live their lives. Recent studies show that many high-income countries have rising rates of childlessness, that people are becoming parents later in life, and that they have fewer children overall. These trends are due to changing priorities and to young people's financial insecurity. When people's careers stall, they also delay starting a family. Lacking stable income and experience early in their careers, many young adults can't afford housing, weddings, childcare, or the long-term costs of raising children.

Predictions about automation exacerbate these concerns. Large-scale studies suggest that computers could handle a substantial amount of routine office and factory work by 2030 if companies adopt these technologies quickly. Even if adoption is slow, there will still be significant changes in employment. Constant changes in the job market will create groups of people with interrupted work histories. These interruptions will lead to lower rates of homeownership, fewer children, and a bigger wealth gap between generations. Countries with weak social safety nets and not enough affordable housing will be the hardest hit.

We're already seeing signs of a dividing line. A small group is benefiting from new technologies and high-skill jobs, while a bigger group faces falling wages and stalled careers. To fix this, we need to connect job market policies with support for families and housing. This means re-evaluating social safety nets to cushion the impact of early-career setbacks, expanding rental and starter-home programs to make them more accessible to young adults in unstable jobs, and ensuring that vocational and higher education both lead to stable, promotable careers. If education is seen only as a way to earn credentials, the next generation will view higher education as expensive and risky. Instead, we should see education and early employment as a connected system for life, not just steps on a resume.

The connections among having children, housing, and a person's career are derived from recent analyses of fertility rates and labor market projections. While it's not always clear how much one factor causes another, conclusions are drawn from trends and from observations of how employers are hiring.

What educators, employers, and governments should do

Three main things should guide our actions. First, make early-career learning a public benefit that companies cannot fully take away. This could mean providing financial support for apprenticeships linked to mentoring programs. Second, demand that employers be clear about the career paths available for entry-level jobs. They should indicate whether the positions can lead to promotions, the coaching provided, and the skills people will learn. Third, reform financial aid programs to enable young workers to access structured early-career opportunities. This includes housing assistance, transferable benefits, and income credits that enable paid early-career learning.

For universities, the next step is to include these ideas in the curriculum. Degrees must include supervised practice, and results must be verified. This will decrease the value of credentials and provide clearer signals for employers. For employers, creating structured two-year junior programs with clear promotion guidelines will be cost-effective in the long term. Companies that invest in developing their people will have a better-trained, more loyal workforce in the future.

Governments must act on two fronts: provide incentives and create safety nets. Incentives include wage subsidies for companies that run accredited early-career programs. Safety nets include unemployment insurance that can be transferred from job to job and that counts apprenticeship time toward eligibility for benefits and retirement. Without these factors, the job market will create a situation in which people born into the right networks or who receive the right education will have more opportunities than those with talent. That result jeopardizes social unity and economic progress.

Some might assert that these ideas are too expensive or unrealistic. They'll say that governments can't fund every training program and that companies will try to take advantage of the system. These are genuine concerns. The details of how these programs are designed are important. Subsidies should be based on results and monitored, and accreditation must be strict. Though letting the first step disappear has major social costs. Investing now in creating formative job opportunities will reduce future dependency, expand the tax base, and stabilize trends in housing and family formation.

These policy proposals are based on studies of employer behavior and examples of apprenticeship programs. The reasoning is based on models of how people build skills over the long term, rather than focusing solely on short-term costs.

Reports tell a clear story: the first step is shaky, and people are paying the cost. This isn't just about jobs; it's about people's lives. We can treat automation as a tool to make things more efficient and ignore how it's changing careers. Or, we can recognize that when early-career learning is lost, society loses the support system needed to turn potential into a stable, successful adult life. The policy solutions aren't easy or cheap. They don't mean stopping progress. They mean reorganizing how we train workers: rebuilding structured, paid early-career opportunities; changing education to include supervised practice; and connecting housing and family support to career development. That's how we protect the chance to move up in society, support families, and keep economies from breaking into areas of privilege and leaving large swaths of people in stalled lives. The choice is up to us.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Autor, D., Dorn, D. and Hanson, G. (2015) ‘Untangling trade and technology: Evidence from local labour markets’, Economic Journal, 125(584), pp. 621–646.

Burning Glass Institute (2024) The Emerging Degree Reset: How the Shift to Skills-Based Hiring Holds the Keys to Growing the U.S. Workforce at a Time of Talent Shortage. Boston: Burning Glass Institute.

Employer Branding News (2025) ‘The vanishing first rung: How AI is dismantling the graduate job market’, Employer Branding News.

Forbes (2026) ‘As AI erases entry-level jobs, colleges must rethink their purpose’, Forbes, 30 January.

Indeed Hiring Lab (2024) Labour Market Trends Report 2018–2024. Austin: Indeed.

International Monetary Fund (2024) Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work. Washington, DC: IMF.

McKinsey Global Institute (2023) Generative AI and the Future of Work in America. New York: McKinsey & Company.

Petrova, B., Sabelhaus, J. and others (2024) ‘Robotization and occupational mobility’, Brookings Institution Report, Center on Regulation and Markets.

Rest of World (2025) ‘Engineering graduates and AI job losses’, Rest of World.

World Economic Forum (2023) The Future of Jobs Report 2023. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Comment