When Work Disappears, Life Paths Shift: AI and the New Life Trajectory

Published

Modified

AI is reshaping the life trajectory of young adults, not just their jobs Economic insecurity linked to automation delays marriage, housing, and family formation Without structural policy reform, AI will redefine adulthood itself

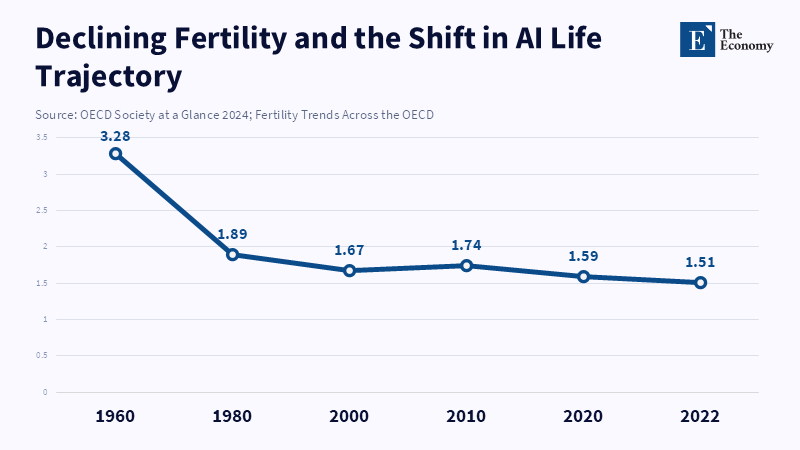

Across the world's richest countries, the traditional path from school to employment to family is no longer working as it once did. Birth rates in developed countries have fallen below the level required to maintain population stability. In 2022, the average was about 1.5 kids per woman, a big drop from the 3.3 average in 1960. People are waiting longer to have their first child, at around age 31. These changes in population were already underway, but now they're encountering significant shifts in the job market due to AI and automation taking over some jobs. AI is changing the nature of work and making it harder for young people to obtain stable employment early in their careers, resulting in greater uncertainty. These aren't merely financial issues; they affect where people live, whom they marry, their relationships, and how they plan for the future. When work isn't a reliable foundation for life, people reconsider when to marry, whether to have children, and even where to live and how to contribute to their communities. So, the challenge for governments isn't just about jobs anymore. It concerns the overall structure of adult life.

How Job Market Changes Are Messing With Life Plans

Work and life milestones have always been linked. Having a steady job, especially when you're just starting out, used to be the basis for major life events like moving out, finding a partner, getting married, and having kids. But there's growing evidence that an unstable job market and changing job structures are having a major impact on how young people plan their lives. When it's hard to find good entry-level jobs or to start a career, young adults don't just face unemployment – they also postpone or scale back on important life decisions.

Researchers have examined birth rates and family trends in high-income countries and have found that each successive generation of young adults is more likely to be childless at every age than older generations. Lower birth rates are part of a broader trend of people waiting longer to marry, have children, or form permanent households – or deciding not to do those things at all. These changes are occurring alongside shifting social views, economic challenges, and other lifestyle changes. However, they also reflect the job insecurity created by major economic changes. When people start their careers in their twenties with uncertain incomes, limited opportunities for promotion, and frequent job changes, it's harder to follow the traditional path of settling down and starting a family.

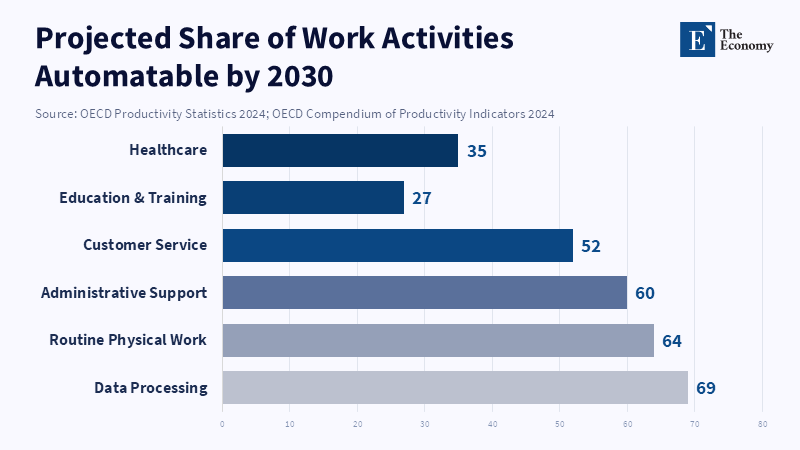

AI plays a big role in all of this. Machines aren't just replacing simple tasks. They're changing what work is like and how opportunities are spread out. In the past, machines mostly replaced routine, physical labor. But today's AI systems are starting to affect jobs that require cognitive and problem-solving skills. According to the OECD, many young people in developed countries are increasingly taking on part-time and temporary work because full-time or permanent employment opportunities are less available, making stable employment harder to find than in the past. When employment is perceived as uncertain and temporary, people's life choices reflect that uncertainty.

Together, these trends indicate both a weakening of upward mobility and a narrowing of the first step into stable careers. This leads to a chain reaction. When people earn less income, they postpone decisions about housing, saving, and family planning. Housing costs are rising faster than wages in many places, which is unsustainable if incomes aren't keeping up. Young adults find it more difficult to achieve traditional milestones of adulthood. The combination of an unstable job market and these economic barriers can affect when people decide to get married, have children, or even whether to commit to long-term relationships.

Delayed Marriage, Lower Birth Rates, and Money Worries

Research from developed countries shows a clear pattern: people are getting married later, or not at all, and they expect to have fewer children over their lifetimes. Data from recentcades show that birth rates in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development have fallen to record lows, and more young adults are choosing not to have children. This decline in birth rates and delays in starting families isn't just a matter of personal preference. They're also caused by a mixture of social and economic pressures, including the challenges young people face in the job market.

When making decisions about having children and starting a family, people consider not just their personal desires, but also their financial security, social norms, and available options. Having children has become just one of many lifestyle options, and as there are more choices and greater financial risks, some young adults delay childbearing or make it a lower priority. This change appears to be influenced by factors specific to this generation, such as longer education, high housing costs, and less predictable career earnings.

Recent data also suggest that young adults in some areas are less interested in marrying and having children. Surveys conducted through 2024 indicate significant declines in expectations for both marriage and birth rates among young people, even as governments have sought to encourage higher birth rates through incentives. According to the OECD, fertility rates in developed countries have declined by half over the past 60 years, altering traditional life milestones, market unpredictability, and the desire for independence, which influence people’s choices. The OECD does not identify artificial intelligence as a direct factor in determining birth rates. Instead, by making it harder to start a career and making stable employment less certain, AI-related changes in the job market increasemonetary uncertaintyy at key ages. And that financial uncertainty is strongly linked to delays in marriage and starting a family. Without predictable incomes and clear career paths, young adults postpone making major life decisions that depend on each other – and this pattern is becoming more common with each new generation.

Housing, Money Problems, and the Future of Adulthood

Financial insecurity does more than just delay family formation. It changes people's lives completely. Housing markets in many developed countries have become less affordable for young adults, with housing prices substantially higher than incomes relative to historical levels. When stable income paths are disrupted by machines taking over jobs or by uneven job growth, it's harder for young people entering the job market to buy homes. This changes how people define adulthood and what they aim for.

There's a cycle between job market uncertainty and housing affordability. When young workers have unstable jobs or experience income fluctuations, they save less, postpone home purchases, and delay long-term commitments such as marriage and children. This, in turn, might lead to lower birth rates and long-term changes in population. In countries where birth rates are already too low to sustain the population, this can have major consequences for future economic growth, social security systems, and intergenerational support.

AI's influence here is fundamental and indirect, but it's strong. By increasing inequality in job markets and concentrating high-paying jobs in specific areas, it leaves generations with fewer opportunities, without the financial foundation needed to make long-term life commitments. This is part of a broader trend of life-stage insecurity, in which the traditional path of work → housing → family is no longer as reliable as it once was.

When the future fefeels doubtfulyoung adults also change their goals. Some put off having children indefinitely. Others focus on flexible lifestyles, starting their own businesses, or doing temporary work that doesn't provide stable, long-term income. The choices individuals make accumulate to create patterns that reshape societies, including older populations, delayed fertility, and changing household structures.

Rethinking Society's Approach: From Job Markets to Life

If machines taking over jobs aren't just replacing tasks but are also changing the structure of adult life, then the government's response must go beyond just job training or unemployment benefits. This is a wider social shift that requires a coordinated approach involving job markets, housing, family support, and financial security – not just simple isolated solutions.

First, job market policies need to recognize that having a stable job early in your career is important for shaping your life. Policies that encourage and support structured early work experiences – even as machines change what those jobs involve – can provide the financial foundation young adults need to make major life decisions.

Second, housing and financial support systems require redesign. Affordable starter homes, rent assistance for young adults entering the workforce, and financial safety nets associated with starting a family could reduce the financial burden of transitioning to adulthood. Without these measures, the demographic consequences of persistently low birth rates and a growing elderly population will strain pension systems, healthcare funding, and social cohesion.

Third, families need to adapt to the changing realities of life courses and life paths. Universal childcare support, flexible work policies, and direct financial incentives linked to starting a family may help reduce the delay effect and align with the realities of the job market. Government aid that helps parents maintain income while raising children can make a difference for those considering having children.

Finally, education and lifelong learning systems should teach not just workplace skills but also skills for adapting to different stages of life. When workers can move between careers without economic insecurity or instability, the link between job uncertainty and delayed life decisions weakens.

These policies recognize that technological change andlife coursess are connected. When economic paths become unstable, life plans change. Government policy needs to be comprehensive rather than reactive, connecting employment, housing, family support, and population trends into a coherent social strategy for the age of machines.

The transformation brought about by AI and automation is not merely an economic issue or about machines performing human tasks. It's about the timing and shape of people's lives, especially for future generations. When stable early careers are replaced by unstable work, the traditional path of home, partnership, and children becomes harder to achieve and more like a choice. This change doesn't affect everyone equally, and its consequences are long-lasting and affect institutions. To address it, policymakers need to think beyond only jobs and wages. They need to recognize that life life trajectoriesincreasingldetermined byby economic forces that are changing the definition of adulthood itself. By rethinking job markets, housing policy, family support, and social security together, societies can help make sure that life goals remain achievable rather than being postponed indefinitely. The stakes are high, as it will determine whether young adults can build families, homes, and futures in the age of AI.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Autor, D., Dorn, D. and Hanson, G. (2015) ‘Untangling trade and technology: Evidence from local labour markets’, Economic Journal, 125(584), pp. 621–646.

Burning Glass Institute (2024) The Emerging Degree Reset: How the Shift to Skills-Based Hiring Holds the Keys to Growing the U.S. Workforce at a Time of Talent Shortage. Boston: Burning Glass Institute.

CEPR VoxEU (2026) ‘Cohort changes in fertility patterns and the role of shifting priorities’. VoxEU Column, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Indeed Hiring Lab (2024) Labour Market Trends Report 2018–2024. Austin: Indeed.

McKinsey Global Institute (2023) Generative AI and the Future of Work in America. New York: McKinsey & Company.

Petrova, B., Sabelhaus, J. and others (2024) ‘Robotization and occupational mobility’. Brookings Institution Report, Center on Regulation and Markets.

Rest of World (2025) ‘Engineering graduates and AI job losses’. Rest of World.

Forbes (2026) ‘As AI erases entry-level jobs, colleges must rethink their purpose’. Forbes, 30 January.

Employer Branding News (2025) ‘The vanishing first rung: How AI is dismantling the graduate job market’. Employer Branding News.

OECD (2024) Society at a Glance 2024: Fertility trends across the OECD. Paris: OECD Publishing.

International Monetary Fund (2024) Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work. Washington, DC: IMF.

World Bank (2023) World Development Report 2023: Migrants, Refugees, and Societies. Washington, DC: World Bank.