Northern Europe AI Adoption and Productivity

Published

Modified

Northern Europe AI adoption shows human capital drives early productivity gains Digital skills and English proficiency speed AI integration Policy should prioritise adoption capacity over sovereign model-building

Here's a fact that should change how we think about bringing AI into the real world: Countries where people already have strong computer skills and speak English well are the ones seeing the biggest benefits from AI right now. And guess what? They're not necessarily building their own AI systems from scratch. Basically, the countries that are best at using AI to improve education, accelerate research, and make government work better aren't always the ones with the largest AI labs. Instead, they're the places where people can actually use these tools every day – reading about them, testing them out, changing them to fit their needs, and making them better over time. This is super important because if we focus only on building AI models in our own country and ignore things like teaching people to use them, training teachers, and making sure everyone has basic computer skills, we'll miss out on a much faster, cheaper way to make a difference. The smart move is to spend money on helping people learn and use AI, not just on building our own AI systems.

Northern Europe: Where People Give Them An Advantage

Let's change the way we talk about this. We need to stop acting like building AI and using AI are the same thing. Building AI models is important for a country's place in the world and for business. But being able to use those models well is what really makes a difference for how productive we are, how well our kids learn, and how good our government services are.

Countries in Northern Europe have shown that you don't need to have national companies develop every component of an AI system to benefit from the models being developed worldwide. The key is having people who know how to use them. Their schools train folks to think in abstract ways, solve problems that require different skills, and use English to understand and work with technology. This makes tasks such as learning to use AI tools, testing them, and integrating them into daily work easier for many people.

This isn't just some vague idea about culture. It's a concrete point about how we design our school programs, how we train our teachers, and how much we invest in basic computer skills for everyone. These things pay off big time when there's a good AI model available anywhere in the world.

For example, recent surveys indicate that more than 80% of adults in countries such as the Netherlands, Finland, and Denmark possess strong computer skills. That's way higher than the average across Europe. These countries also score highly in English, which makes it easier for their people to use AI tools, as most instructions, examples, and online communities are in English. This means they can take research or instructions and quickly turn them into something useful for their own work. Because they can do it faster, Firms and schools can test AI, learn from their mistakes, and improve their use of it in weeks rather than months. These time savings accumulate across many areas and explain why these countries can adopt AI as quickly as countries with major AI developers.

We're not saying that having skilled people solves everything. People are important, but they're not the only factor. Factors such as company size, access to cloud computing, and clear rules also play a role. But when people have good computer skills and speak English well, these other problems become easier to solve. We can implement policies, provide financial support, and develop joint projects between the government and businesses to address them. In short, the best way to get real benefits from AI is to have people who can use those models as soon as they become available.

What the Numbers Say

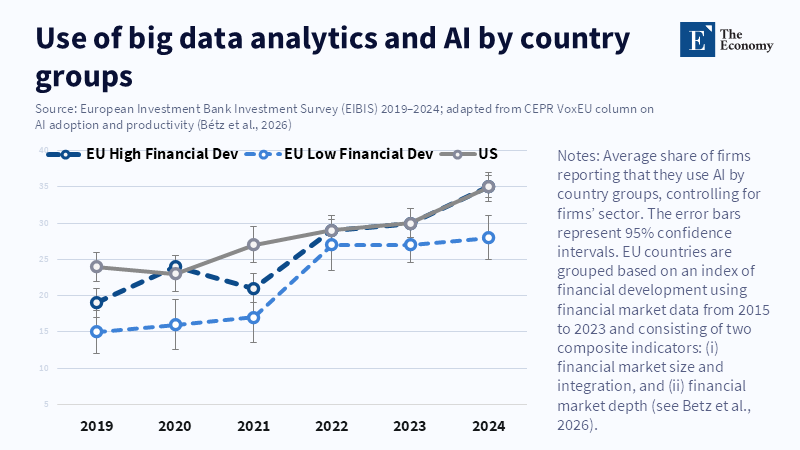

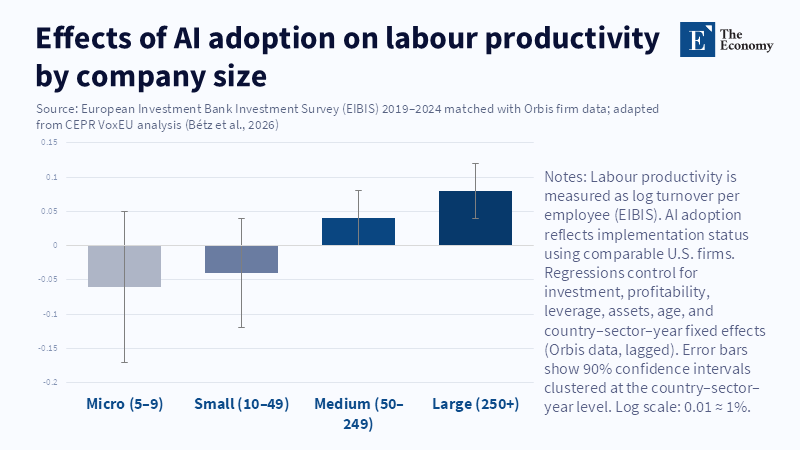

The data supports this: when people have the right skills, using AI leads to greater productivity. Surveys of companies across Europe have found that, on average, worker productivity increases by approximately 4% after they adopt AI. That may not sound like a lot, but it adds up when you consider all the different industries. According to McKinsey & Company, their findings are based on surveys of more than 12,000 companies, and these patterns stay consistent even after accounting for differences in company size, industry, and past growth. The 4 percent figure is not fixed and may vary by country and company type. However, it provides a general idea of the short-term benefits.

So, how do Northern European countries do it? Several sources point to the same points. First, European statistics show that a group of countries in Northern and Western Europe has had much higher rates of basic computer skills than the rest of Europe in recent years. Second, surveys indicate that companies are adopting AI more rapidly in regions where large companies and government services already have robust computer systems. Third, several Nordic countries have government programs that train teachers, retrain adult workers, and make data publicly available, thereby reducing the costs of adopting AI. We examined survey results from companies, national statistics on computer skills, and English language proficiency scores. We also confirmed these trends using data from individual companies whenever possible.

Another important factor is language. Studies show that people who must wait for materials to be translated into their own language experience considerable delays. In some countries where English is less widely spoken, the use of AI in occupational contexts is noticeably lower. This isn't about a lack of talent in those countries. It concerns the additional time and effort required to translate and verify everything. When individuals can read examples and instructions in English, they can experiment and learn more quickly. If they can't, they need someone to translate for them, which slows things down.

What Should We Do?

If getting people to use AI is the key, we need to act quickly. First, we need to invest in training more people to read, think, and use AI tools that are primarily in English. This includes computer classes for adults, short courses on using AI tools effectively, and teacher training that connects AI to what they teach in the classroom. These are smart investments because they make it cheaper for a country to use any AI model that comes from anywhere in the world. Second, governments can create programs that incentivize companies that show they can successfully implement AI and train their staff, rather than just favoring companies that claim to have the best AI technology. For example, they can set up contests that require companies to demonstrate real improvements in areas such as how quickly students are assessed or how well government services are delivered, rather than insisting that companies use AI models developed domestically first. The goal is to encourage faster adoption, not to protect domestic technology.

Third, when language is a real barrier, we should both translate materials into local languages and improve people's English skills. Investing in better machine translation is a good idea. But translation is only a temporary fix. The real goal should be to have users who don't need translations. This means starting English education earlier, improving digital skills, and creating workplace programs where experts work with people learning to use AI. Fourth, don't think that building AI within our own country is a substitute for having skilled people. Building a national AI model is slow and expensive. By the time it's ready, the rest of the world may have moved on. Building domestic AI is important for specific reasons, like protecting privacy in healthcare or creating datasets in local languages. But it shouldn't replace investing in people.

Some will worry that relying on foreign AI models will make countries vulnerable to political pressure or biased AI. This is a valid concern. The solution is to do both: use high-quality AI models from other countries to improve overall productivity and learning, and fund our own AI efforts for specific public-interest projects where control is critical. At the same time, we need to establish standards and verification processes for all AI models in use, and implement governance mechanisms that allow teachers, government workers, and everyday people to raise concerns without halting the use of those models. Combining adoption with careful domestic development is cheaper and faster than building everything ourselves.

What Should Educators, Administrators, and Politicians Do?

- For teachers: Update teacher training to involve short, regular lessons on how to use AI which include how to write prompts, how to spot biases, and how to evaluate them. Combine these lessons alongside small projects in the classroom that demonstrate real improvements in how quickly students are graded or how personalized their feedback is. These projects should use easily accessible tools to make them easier to implement.

- For administrators: Create guidelines for purchasing and evaluating AI tools that value the ability to and train staff to use them

- For politicians: Support programs that give financial vouchers to small and medium schools and local governments to help them experiment with AI. Make these vouchers conditional on teacher training and open reporting of how well the tools are working.

An additional step is measurement. Governments need to use consistent methods to assess how AI is being adopted. It's not enough to know whether a tool is being used; we need to know how and by whom. Surveys of companies and schools already exist; adapting them to a country's context will enable rapid adjustments. Finally, adjust immigration policies to attract the skilled talent needed to drive AI adoption in lagging regions. An influx of teachers, trainers, and AI-savvy government officials can sow local capacity and accelerate diffusion if paired with clear knowledge-transfer conditions.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Bétz, M., Criscuolo, C., Gal, P. and Timmis, J., 2026. How AI is affecting productivity and jobs in Europe. VoxEU, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

EF Education First, 2023. EF English Proficiency Index 2023. Zurich: EF Education First.

European Investment Bank (EIB), 2019–2024. EIB Investment Survey (EIBIS). Luxembourg: European Investment Bank.

European Investment Bank (EIB), 2025. How are EU firms faring with digital AI and big data? Luxembourg: European Investment Bank.

European Commission, 2024. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2024. Brussels: European Commission.

Eurostat, 2024. Individuals’ level of digital skills. Luxembourg: European Commission.

McKinsey & Company, 2025. Accelerating Europe’s AI adoption: The role of sovereign AI. Brussels: McKinsey Global Institute.

OECD, 2025. AI and the global productivity divide. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

OECD, 2026. AI use by individuals surges across the OECD as adoption by firms continues to expand. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Reddit, 2025. Data from 12,000 firms in EU and US finds that AI increases productivity by around 4%. r/science discussion thread.

Van Roy, V., Vértesy, D. and Vivarelli, M., 2023. AI adoption and firm productivity in Europe. Luxembourg: European Commission Joint Research Centre.

Comment