When Probable Words Mislead: Reframing LLM Limitations as a Decision Risk

Published

Modified

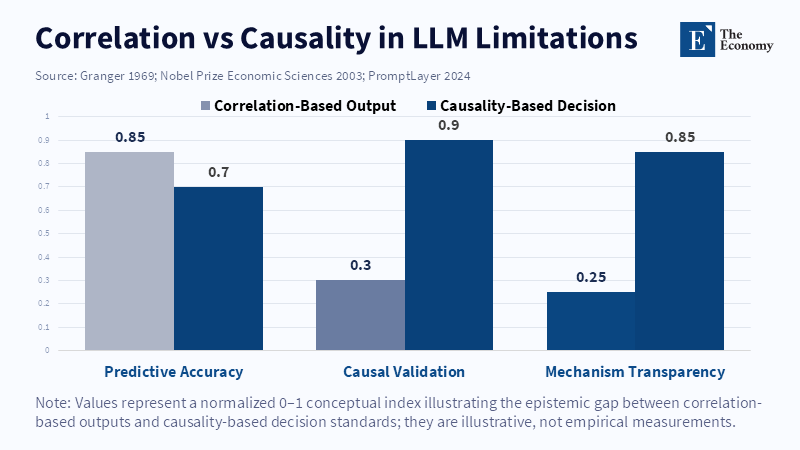

LLM limitations stem from confusing probabilistic fluency with real causal reasoning Hallucination and poor judgment arise because models generate a linguistic silhouette of reasoning, not true intelligence High-stakes decisions require causal validation, not correlation masked as confidence

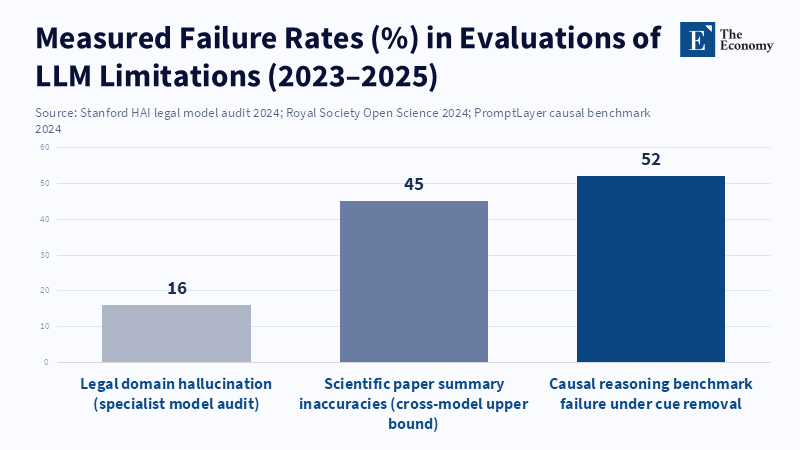

Large language models (LLMs) aren't merely facing minor problems; their shortcomings can seriously mess up the decisions we make. Recent checks on legal LLMs showed they made up stuff—called hallucinations—in about one out of six questions. When these LLMs tried to summarize information in science, they gave the wrong answer more than a third of the time. And it's not just old LLMs that are the issue; even the newest ones with better language skills sometimes confidently spout nonsense. We can't think of LLMs as having brains like us. They're basically just really good at spotting patterns and making lines that sound like they make sense. They can create a convincing picture of reasoning, but they don't actually understand why things happen. So if teachers, managers, and politicians treat these LLM-generated sentences as actual reasoning, they might confuse a guess for a fact. This mistake could cause them to change policies, school budgets, and how students learn in ways that are difficult to reverse. The major concern isn't just that LLMs sometimes lie; it's that they seem trustworthy while giving us no real way to check whether what they say is based on evidence, a random pattern, or simply echoes from their training data.

LLM Problems: False Info and Bad Decisions

One major problem with LLMs is pretty obvious: they make up stuff. They can invent facts, quotes, or stories that never happened. This isn't just stretching the truth; it's LLMs creating complete lies when they don't know the answer or get a confusing question.

The other problem is more complex: poor judgment. An LLM might give an answer that appears correct because it has identified a strong pattern in its training data. But it doesn't really understand why that answer makes sense. The answer appears to be based on reasoning, but it's really just a superficial match of patterns from large amounts of text. This can obscure major errors in how LLMs infer cause and effect and assess risk. This is risky for teachers and politicians who must consider different options. An LLM might suggest a textbook, change the order of classes, or try out a new teaching method just because those things often appear together in texts with certain results. That's just spotting a pattern, not understanding the real cause. If decisions are made like that, money could be wasted and students could be harmed.

The difference between these two problems is important because we need different solutions for each. We can reduce made-up information by having LLMs rely on verified sources, check quotes, and warn us when they're unsure about something. But bad judgment needs way more work: experiments, tests to find the real cause, and checks by real people. But many places just insert a quote or a disclaimer to the LLM's answer and think they've fixed both problems. That only deals with the surface issue, not the deeper problem. Giving LLMs access to more info will reduce made-up stuff, but it won't turn a pattern into real understanding.

Proof, Estimates, and a Quick Note on How This Was Studied

The real numbers indicate that this is a serious problem. Checks from 2023 to 2025 show the same things: LLMs that specialize in certain topics make up stuff at a noticeable rate when asked questions about those topics; LLMs that sum up info frequently exaggerate or get the sources wrong; and LLMs that are tested on cause-and-effect reasoning show some progress, but it's not consistent and easily falls apart.

If you want to know how big the problem is, here are three examples from public checks: one study found that legal LLMs made up stuff in about one out of six questions in realistic legal situations; another study found that LLMs summarizing science papers had mistakes in about 30–70% of the summaries, depending on the LLM and the question; and experiments on LLMs' ability to reason about cause and result show that they can learn to copy patterns when given examples, but they fail when the examples are changed.

It's important to be careful when interpreting these numbers. Different checks have different ways of defining what counts as incorrect or fabricated. Some count any invented quote as made up, while others only count factual errors. For cause-and-effect tests, researchers often create tricky questions that remove clues; LLMs that appeared capable then fail. These choices about how to test LLMs are important because they distinguish between merely sounding good and actually understanding something. When we say one in six or one in three, we're not saying that every LLM will make that mistake every time. We report the rates of errors observed under specific, realistic situations designed to replicate how these LLMs are used in real decision-making. Those are the situations that matter to managers deciding whether to trust a recommendation from an LLM.

What This All Means for Teachers, Managers, and Policy Makers

First, don't treat LLM answers as the final truth. Whether it's a transcript, a policy suggestion, or a lesson plan, don't accept it without a human double-checking it, especially if the decision is important. This means adopting a simple rule: for decisions with a big impact, have someone review the reasoning behind them, not just the facts.

Second, invest in simple ways to validate LLM answers. For example, require that any program suggested by an LLM include: (a) a clear statement of the cause-and-effect relationship; (b) at least two independent sources or a list of where the info came from; and (c) a plan to test it out, even if it's just a small trial. These steps prompt a human expert to consider the reasoning rather than simply trusting the LLM's smooth-sounding answer.

Third, change how you buy and manage LLM services. Contracts for LLMs should require companies to be transparent about where the training data came from, how often the LLM makes up content in similar situations, and what they will do if the LLM causes harm. Policy makers should require independent checks for critical uses of LLMs in education, similar to financial audits, but focused on how LLMs can fail.

Fourth, update training for professionals. Teachers need to learn how to distinguish between a cause-and-effect story that sounds good and one that's backed by evidence. Teachers should be trained to design simple checks: basic before-and-after analyses, quick checks for other factors that could be involved, and quick tests with small groups. These are low-cost ways to test whether an LLM's recommendation holds up when inputs change.

Some might say that these checks slow down innovation or that human validation is too expensive. But the cost of making decisions without checking is already high: wasted money, poor teaching plans, and policies that must be reversed harm schools and students. Also, validation can be adjusted based on the situation. Big changes that affect many students or cost a lot of money should undergo full experimental checks, while smaller suggestions might just need a simple check of the source. The point isn't to stop innovation, but to shift trust away from smooth-sounding language and toward real understanding of cause and result.

Changing How We Think About Responsibility: From Illusion to Trust

LLM designers and sellers need to stop acting like smooth language means understanding. Marketing that claims to be more reliable is harmful. Instead, companies should provide clear signals of how confident they are in an answer and where the information came from, and explain the tests they ran to measure how often the LLM makes up information and how well it reasons about cause and effect in realistic situations. Regulators can require standardized reports on education-specific LLM issues. These reports should include how often the LLM makes up stuff when asked about educational topics, examples of how the LLM fails, and details on how the LLM handles questions about cause and result.

Schools that use LLMs need to create clear roles and responsibilities. Who checks the LLM's answers? Who is responsible when an LLM-powered decision harms a student or wastes money? These questions can't be left to the LLM vendor. One practical step is to establish internal review boards—groups that include teachers, statisticians, and experts—to review key applications of LLMs. These boards should publish examples of times when LLMs failed and how those failures were corrected so that everyone can learn from them. The value of these boards isn't just about regulation; it's about learning. They force us to question cause-and-effect claims and assess whether an LLM's picture of reasoning aligns with what we can test.

Finally, we need to change how we measure success. Too often, we focus on smooth language, user satisfaction, or test scores that reward LLMs for sounding human. For education, success should mean being truthful under testable conditions and helping people understand cause and result. That means funding research to make LLMs more grounded in reality, improve their information retrieval, and create interfaces that show how uncertain an LLM is in ways that are easy for non-technical users to understand.

In conclusion, we're at a turning point. LLM problems won't disappear just because LLMs get smoother and better convincing. The biggest risk is that we'll change schools to fit the illusion of intelligence rather than accept the real limits of pattern-based systems. The solution is simple and practical. Demand understanding of cause and result where decisions matter. Require companies to provide information on where the data came from and how often the LLM generates misinformation. Train people to test LLMs, not just read their answers. When teachers, managers, and policymakers do these things, we can use LLMs without putting people at risk. The linguistic picture of reasoning created by LLMs can be useful, but it shouldn't be how we decide what's true. We should use LLMs for what they're good at—generating drafts, finding patterns, and suggesting ideas—and then have humans use their judgment, backed by simple tests, to complete the process.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Aionlinecourse.com (n.d.) Granger causality. Available in AI Basics course materials.

Brundage, M., et al. (2024) Factuality of large language models in the year 2024. arXiv preprint.

Hansen, L., et al. (2024) AI on trial: benchmarking hallucinations in legal large language models. Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) report.

Nobel Prize Outreach AB (2003) The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2003: Popular information. Stockholm: Nobel Prize Outreach.

PromptLayer (2024) Can LLMs learn cause and effect? Research report.

Royal Society Open Science (2024) Accuracy and exaggeration in AI-generated summaries of scientific research. Royal Society Publishing.

Scientific American (2023) AI and human intelligence are drastically different — here’s how. Scientific American.

Smith, J., Patel, R. and Nguyen, T. (2024) Benchmarking hallucination in large language models. arXiv preprint.

Comment