Stop Chasing Ghosts: Why Policing AI Won’t Stop Students from Using ChatGPT — and What Will Focus SEO keyword: prevent ChatGPT cheating

Published

Modified

AI use in schools is widespread, and surveillance alone will not prevent ChatGPT cheating Redesigning assessments to reward process and reasoning makes shortcutting less attractive Policy must shift from detection to incentive design to reduce reliance on ChatGPT effectively

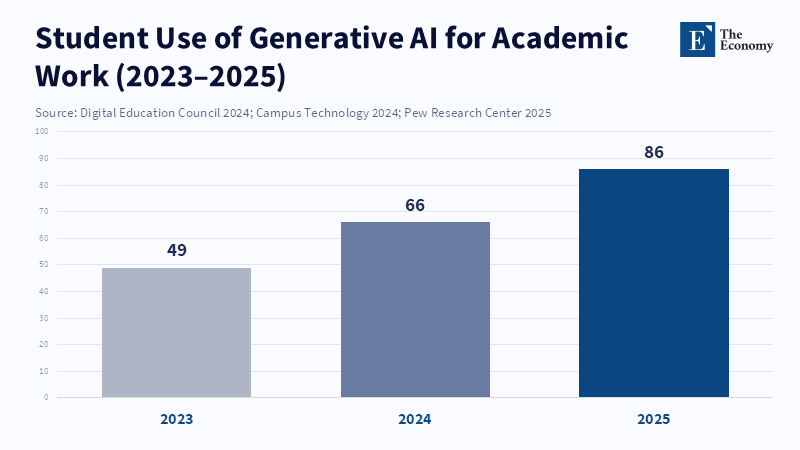

By the academic year 2024–2025, a considerable number of students, exceeding half, report the routine use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools within their academic practices. This trend isn't a temporary phenomenon but signifies a fundamental change in how students approach drafting, conducting research, and polishing their academic work. To frame the issue as simply how to stop students from using tools like ChatGPT is to misinterpret the problem, focusing on a symptom rather than the underlying cause. Such a frame directs educational institutions toward methods of detection, surveillance, and punitive measures, all of which are expensive to implement, easily circumvented, and potentially detrimental to fairness and equality.

If the goal is to reduce the inappropriate reliance on AI tools like ChatGPT, the focus needs to shift away from surveillance as a primary strategy. Instead, there should be a reformation of the incentives and the fundamental design of both assessment and instruction. This analysis asserts that focusing on policing the use of AI in education will, at best, only slow down its adoption. At worst, it could distract educators from more valuable pedagogical endeavors. In response, there is a need for a policy framework that makes the misuse of AI more difficult while simultaneously promoting its ethical and intelligent implementation in education. Practical design modifications are needed to increase the effort required for academic dishonesty and to properly reward students for skillful and transparent AI use.

The Misinterpretation: Technology Policing Instead of Incentive Restructuring

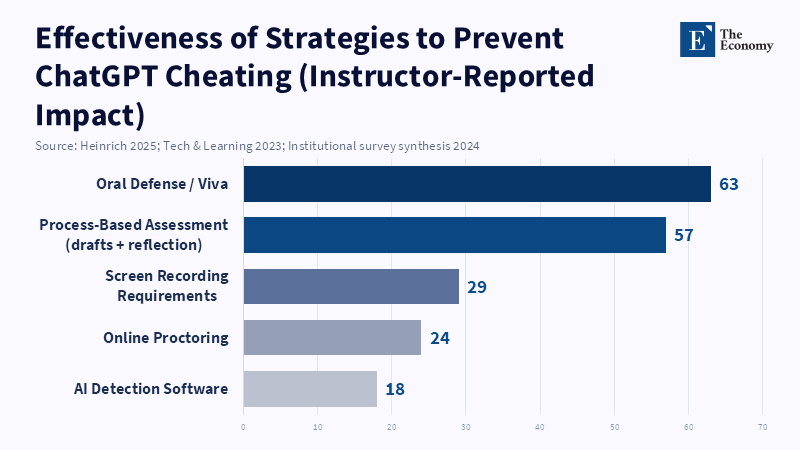

Educational institutions have reacted to AI primarily as a tool for rule-breakers, leading to the creation of systems to detect and punish its use. For example, while some academic departments have adopted stricter assessment measures, such as requiring students to record their computer screens during tests or returning to handwritten exams, others are reviewing their use of AI-detection software. According to Diplo, Vanderbilt University recently decided to disable Turnitin’s AI detection tool due to worries over its reliability and transparency. These measures represent the ongoing effort to tackle potential loopholes as new technologies emerge. What these reactions fail to recognize is that any new technology changes behavior by altering the perceived costs and benefits of various actions.

When students can generate a passable first draft in mere minutes using AI, the cost of cheating, measured in time and effort, decreases significantly. If educators respond by increasing surveillance, the emotional and privacy costs for students rise, which shifts the classroom environment from one of trust to one of suspicion. These surveillance tactics also disproportionately affect certain students. Students who have access to dependable internet and quiet study spaces, and who are already familiar with proctoring technologies, are less burdened by augmented surveillance. However, students with caregiving responsibilities, unstable internet connections, or privacy matters face greater challenges. Therefore, the consequence is not necessarily a reduction in dishonest behavior, but rather a reduction in impartial opportunities for all students. To decrease the misuse of AI tools like ChatGPT for dishonest purposes, policy should aim to make academic dishonesty less appealing and make academic honesty more accessible.

Policing the use of AI also leads to a misallocation of teacher effort. The time educators spend interpreting AI-detection reports, managing proctoring applications, or reviewing screen recordings is time not available for formulating engaging tasks or providing detailed coaching on argumentation. Initial information and institutional feedback suggest educators are saving time by using AI for lesson preparation and grading; however, the focus on surveillance causes teachers to revert to manual review, negating those efficiency gains. It would be more useful for teachers to spend their time on tasks that develop students’ AI skills. They could teach them how to write effective prompts, check sources, and use progressive feedback. Shifting educators' focus to these higher-value activities will assist students more than policing AI use. The central policy question should not be how AI use can be stopped. But rather, how can reward structures be changed so that students get more out of legitimate learning than from simply gaming the system using technology?

Evidence: Common Usage, Flawed Detection, and Costly Controls

Current information provides clear insight for policy creation. A number of surveys done between 2023 and 2025 show a high rate of AI adoption among students. Both global and national surveys show that many students, from around two-thirds to over 80 percent, routinely use AI tools for study-related work, with many using them weekly or daily. AI use isn't an occasional experiment; it's a regular activity for students. Current detection tools continue to improve, but they still have flaws. Major vendors acknowledge that their tools produce false positives and need calibration. Detection scores in certain ranges are unreliable, so colleges must interpret them carefully. Institutional data shows that policing AI use produces varied results. According to a recent article, universities have adopted AI detection tools at varying rates, and many institutions still lack guidelines or enforcement procedures for their use, making it difficult to determine whether surveillance actually reduces general misconduct. Proctoring and screen recording also involve expenses to student privacy, equality, and well-being, which many institutions only start to measure. Accepting these three things—common usage, flawed detection, and costly controls—should reorient how policy is discussed, moving it away from competitive tactics and toward system reform.

A Practical Reformulation: Increasing the Educational Cost of Shortcutting and Decreasing the Cost of Authentic Work

If the core of the problem is incentives, the key is to redesign them. There are five interconnected methods that can make the appeal of academic dishonesty less attractive. They can increase the rewards of legitimate academic work. The first is to change assessments so they require evidence of the process that generated them. This includes drafts, revision logs, annotated source notes, and short videos. These additions make a single AI-generated final product less useful because students have to show their chain of thought. Second, break split tasks into smaller activities that require on-the-spot knowledge. These could include class debates, quick low-stakes writing assignments, and short presentations. Constant learning across multiple formats can't be replaced by a single prompt elsewhere. Third, give students specific training in writing effective prompts. They'll learn how to use AI to repeat tasks, to critique results, and to check evidence. In this setting, AI transforms from a shortcut into a tutor. Fourth, set aside high-trust, in-person time for assessments. This might be via oral exams, project defenses, and supervised labs. Students could then use AI-enabled tasks for practice. Fifth, have grades reflect process and thinking instead of just polished writing. Together, these actions shift the calculation. They reduce the reward of depending on an outside source and increase the value of doing the work.

There is no need for a fancy method of putting things into action. A basic system of a quick in-class warm-up, a take-home draft with annotated sources, and a five-minute video makes it harder for a student to simply use AI to get an easy grade. The study by Mazaheriyan and Nourbakhsh does not provide specific findings on whether teachers consider the system manageable or whether it shifts the balance between assignment management and students' incentives to use AI. The system also keeps things fair. If students have limited time, they can be given flexible time frames to demonstrate their knowledge, rather than being forced into high-tech surveillance that punishes them based on their home situation. To put it briefly, this plan will make cheating take more work than simply learning and make learning easier and clearer.

Anticipating and Dealing with Concerns

A common rebuttal is a practical one: We don't have time to change every assignment. That's a valid point, but it also shows a failure in management when large budgets are spent on investigating misconduct while there is no time for teachers to improve their teaching. Small design changes, like having two required drafts, a class presentation, and a short discussion, are inexpensive but have a big impact. Another concern is that those who are determined to cheat will still find ways to manipulate the system. That's true because no system is totally workable. Plans should aim to reduce misconduct and detect high-stakes fraud, not to achieve the impossible. A more important point is that using AI pedagogically can make its misuse feel normal. That's why prompt writing skills are important. Students need to learn both how to use AI and how to judge, cite, and critique its work. Banning AI won't stop people from gaining access to it. It is better to teach students useful skills than to ban convenience. Last, there are worries about what regulators and employers will expect. Will graduates be trusted if AI use is allowed? The answer is that skills must be certified. Students must demonstrate clear thinking in professional situations through portfolios, presentations, and tasks that showcase their abilities. That sends a stronger signal than policing ever would.

Studies show concerns about proctoring and monitoring are valid. Some controlled studies show that proctoring decreases some types of violations. Even so, the rewards are varied and come at the cost of student stress and privacy. Reports also display that flags from detection software often need to be followed up manually, which is hard to manage. Considering this information, focusing heavily on monitoring yields lower rewards than the effort required to redo assessments.

Policy Actions for Directors and Policy Makers

Directors should move resources from punishments to teaching-related work. Small groups should be funded whose specific job is to change courses to show learning and to create templates for project steps with short discussion scripts. To encourage change, give teachers time to try out changed assessments and measure results by demonstrated skills, not just detected misconduct. Policy makers should avoid wide bans on AI or strong requirements for invasive monitoring. Instead, they can fund research on low-cost ways to verify learning, such as short oral defenses and portfolio verification. Accreditation groups should update their rules to accept process evidence and tests as valid signals of ability. These steps shift the system from punishments to active education.

For classrooms, coaching programs can prepare every teacher to require two definite steps. Students must show how they do their work and explain their choices. When students know they'll be questioned and need to defend their work, shortcuts become less useful. That's the action policy that must be followed.

AI is widely used, and policing is not a good long-term choice. Policy makers must make a straight choice. They can increase surveillance at a great cost and low returns, or change systems so that honest work is safer, more accessible, and more valuable than a quick AI draft. The second choice needs to focus on teaching-related design, clearer grading to reward process and thinking, and a course that teaches students to review AI in detail. It will be difficult and will require organization. AI can then change from a shortcut to a tool. Responsibility and confidence can then be restored, and students will be discouraged from cheating.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Heinrich, E., 2025. A systematic-narrative review of online proctoring: Unpacking effectiveness, equity and student experience. Open Praxis, 17(3).

Sullivan, S., 2024. Yes, you can stop students from using ChatGPT: Rethinking assumptions about trust and assessment design. Substack Newsletter.

Tech & Learning Editorial Team, 2023. I asked ChatGPT how to stop AI cheating—here’s what it said. Tech & Learning.

Turnitin, 2023. Understanding false positives within AI writing detection capabilities. Turnitin Guidance Report.

Turnitin, 2026. AI writing detection in the enhanced similarity report: Product overview and technical note. Turnitin Technical Documentation.

Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching, 2023. Guidance on AI detection and instructional implications. Vanderbilt University Teaching Resources.

Vox Editorial Staff, 2024. AI, cheating and the future of classroom trust. Vox.

Wong, A., 2023. A veteran teacher explains how to use AI in the classroom the right way. Scientific American.

Comment