Donald Trump Says He Secured “Unprecedented Funding” From South Korea and Japan for Alaska LNG

Input

Modified

Plans focus on securing LNG development funding and sales channels

Transport distance and long-term contracts remain key burdens

Energy vulnerability risks similar to Europe also present

U.S. President Donald Trump presented trade agreements with South Korea and Japan as key achievements of the past year, linking them directly to his medium- and long-term energy strategy. Against the backdrop of a global energy landscape reshaped by reduced reliance on Russian gas, Trump outlined a plan to elevate U.S.-produced liquefied natural gas (LNG) as a new export pillar.

He argued that trade deals with allies, investment commitments, and energy supply negotiations would be tightly interconnected in this process. South Korea, however, has maintained a cautious stance, raising questions about whether Trump’s vision will translate into concrete investment decisions or actual project execution.

Combining tariff pressure with security cooperation

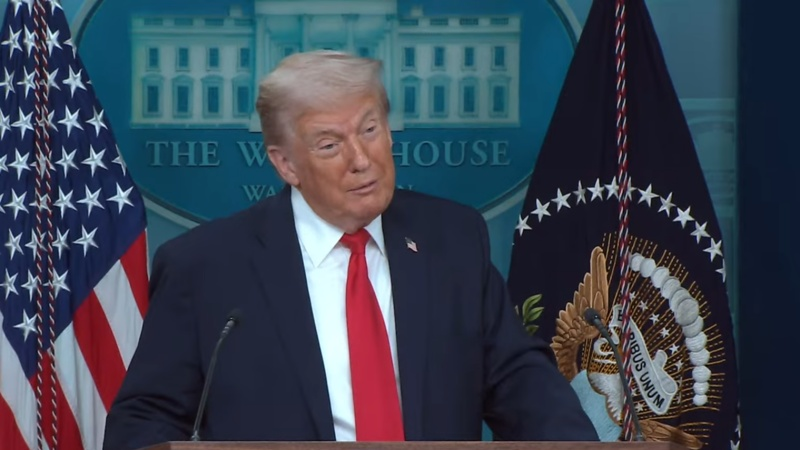

On the 20th local time, Trump said at a White House press conference marking the first anniversary of his inauguration that the United States had concluded trade agreements with South Korea and Japan, securing “unprecedented levels of funding,” and had launched the Alaska pipeline project to export natural gas to Asia. During the roughly 80-minute briefing, he bundled tariffs, foreign investment inflows, and energy development into a single narrative of policy success. The Alaska LNG project was presented as a symbolic case of reallocating large volumes of overseas capital, obtained through tariff leverage, into strategic industries within the United States.

Trump focused less on the project’s profitability or business structure and more on the financing framework. He stated that South Korea and Japan had pledged investments of $350 billion and $550 billion, respectively, and that in return, mutual tariffs were reduced from 25% to 15%. He repeatedly emphasized that these investments were made possible by tariffs, underscoring a circular logic in which tariffs attract capital that is then reinvested in core domestic industries.

The Alaska LNG project involves transporting natural gas produced in Alaska’s North Slope through a roughly 1,300-kilometer pipeline, liquefying it, and exporting it to Asian markets. Initial project costs are estimated at $45 billion, with funding allocated to pipeline construction and liquefaction facilities. Trump described the project primarily as a pipeline initiative and said it would form the foundation for long-term U.S. gas supplies to allied markets. His remarks suggested an intention to offset the project’s weaker price competitiveness compared with Russian LNG through demand anchored by allies.

This vision aligns with a broader perception of an energy and economic bloc centered on the U.S., Japan, and South Korea, contrasted with a Russia–China–North Korea axis. While Trump did not explicitly frame the Alaska LNG project in geopolitical terms, his simultaneous references to security cooperation implicitly placed it within an alliance-strengthening narrative. Domestically, however, skepticism persists over whether such a high-cost infrastructure project can be realistically executed. Federal permitting, environmental regulations, and funding disbursement procedures are expected to determine the pace of the project.

Alaska LNG as an option, not a necessity

Participation by U.S. allies remains uncertain. South Korea has consistently maintained a cautious position despite repeated U.S. requests to join the Alaska LNG project. The most immediate concern lies in commercial viability. Investments in energy infrastructure typically require long-term purchase agreements to ensure cost recovery, and the LNG market’s price volatility and demand uncertainty pose significant risks. The South Korean government has previously stated that the Alaska project is still undergoing feasibility review based on commercial rationality, with no conclusions reached.

The trajectory of the war in Ukraine and potential changes in access to Russian energy supplies also represent key variables. As the conflict moves toward its later stages, the scope for procuring Russian energy may widen, reducing the necessity of long-term commitments to high-cost Alaska LNG. Data underscore this point. As of May last year, South Korea’s imports of Russian LNG reached $135 million, the highest level since November 2024, reflecting an increase of about 80% from the previous month and roughly 25% year-on-year.

Institutionally, South Korea is not in a position where participation in the Alaska LNG project can be forced. A memorandum of understanding on strategic investment between South Korea and the United States explicitly grants Seoul discretion to refrain from investing in specific projects on grounds such as insufficient commercial viability. While an investment committee chaired by the U.S. Secretary of Commerce plays a central role in selecting investment targets, South Korea conveys its position through a consultative committee. Nonetheless, concerns remain that South Korean preferences may not be fully reflected in practice, particularly as U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick has publicly cited energy infrastructure as a priority area for joint investment.

In this context, South Korea’s distancing reflects a calculation that weighs both supply flexibility and cost structure. Even after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, Russian energy imports were not entirely cut off. Within the framework of international sanctions, South Korea has continued to apply limited exemptions in the energy sector. This suggests that while Alaska LNG may come under consideration amid political and diplomatic pressure, it is difficult to regard it as an essential or unavoidable path given prevailing economic and market conditions.

Europe’s reality of heavy reliance on the United States

Europe likewise lacks strong geographic or logistical incentives to turn to U.S. LNG. Historically, European consumption has centered on LNG from the U.S. mainland rather than Alaska. However, the sharp reduction in Russian gas imports has turned Europe’s growing reliance on U.S. LNG into a constraint. In a report released on the 19th, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis said that the EU’s promotion of U.S. LNG imports had resulted in a high-risk structure characterized by high costs and dependence on a single supplier, noting that Europe’s effort to replace Russian gas ultimately led to overconcentration on another source.

The data make this shift clear. EU imports of U.S. LNG rose from 21 billion cubic meters in 2021 to 81 billion cubic meters last year, nearly a fourfold increase. Over the same period, imports of Norwegian gas remained stable at around 90 billion cubic meters annually, while imports of Russian gas, including pipeline gas and LNG, fell by 75% over four years. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU agreed on phased measures to ban LNG imports from late 2026 and pipeline gas from autumn 2027.

U.S. LNG quickly filled the gap, and as a result, five countries—the Netherlands, France, Spain, Italy, and Germany—now account for 75% of total U.S. LNG imports into Europe. The concern is that this dependence will continue to deepen. The IEEFA projects that by 2030, the EU could source up to 80% of its LNG imports from the United States, amounting to roughly 115 billion cubic meters annually. Across Europe as a whole, the U.S. share of total gas and LNG imports could rise to 40%, up sharply from 27% last year.

This trend raises the prospect of conflict with the EU’s REPowerEU strategy, which prioritizes supply diversification, reduced gas demand, and price stability. U.S. LNG is widely regarded as the most expensive among the EU’s LNG supply sources. The IEEFA estimated that the $750 billion the EU plans to spend on U.S. energy purchases could instead fund an additional 546 gigawatts of solar and wind capacity, arguing that renewable energy investment may offer a more rational option in terms of cost and energy autonomy.

Europe’s experience offers South Korea an indirect point of comparison. The process of reducing reliance on Russian gas while rapidly increasing dependence on U.S. LNG brought both cost burdens and energy autonomy concerns to the fore. Ana Maria Jaller-Makarewicz, the IEEFA’s lead energy analyst for Europe, said that while the EU succeeded in breaking its dependence on Russian gas, that achievement came with a new vulnerability rooted in strategic reliance on U.S. LNG. The European case illustrates that prolonged dependence on a single supplier changes the form of energy insecurity but does not eliminate it.

Comment