The Trump G20 agenda: shrinking the forum to project U.S. power

Input

Modified

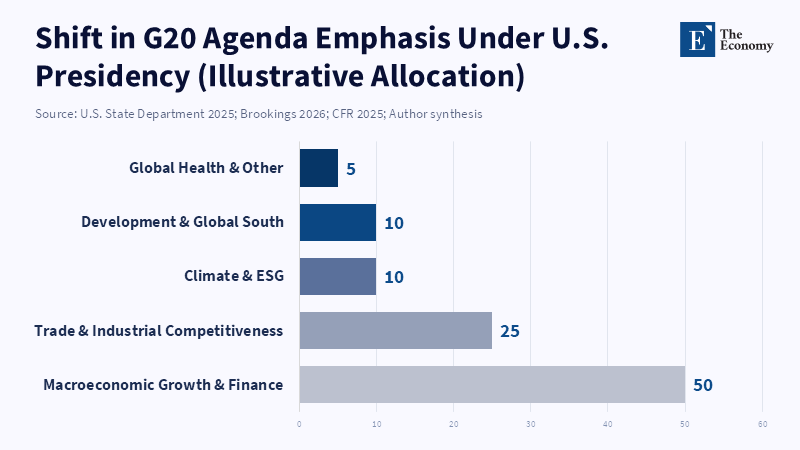

The Trump G20 agenda narrows the forum to economic power projection It shifts focus from ESG cooperation to U.S.–China competition Institutions must adapt to a more fragmented global order

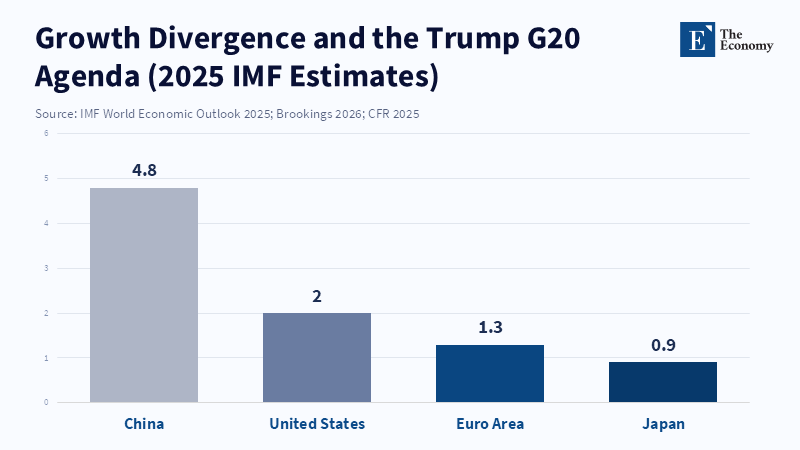

When the U.S. decided to skip the Johannesburg leaders' meeting in late 2025, it was more than a simple oversight; it was a calculated move to send a strategic message. This act signals a major shift: at a time when China's economy is growing about twice as fast as the U.S. economy (around 4.8–5.0% compared to about 1.8–2.4% in 2025), international meetings increasingly focus on showcasing national strength rather than fostering cooperation. The main argument is that the G20—once a forum for joint solutions—is being repurposed as an arena for major economies, particularly the U.S. and China, to compete. The Trump G20 plan embraces this shift, intentionally reducing meeting size and excluding topics such as environmental and social issues, as well as broader climate or development commitments. In doing so, it leverages the G20 presidency to signal that the U.S. prioritizes economic competition with China over global problem-solving. This deliberate redefinition changes who makes the rules, what is measured as success, and which government departments lead. The central argument is that for those in education and public policy, this refocusing compels new strategies: how do we teach and govern when the G20 shifts from solving global challenges to a stage for power competition?

Trump's G20 Plan: Focusing Only on Finance

This is a structural change. The U.S. Treasury says the U.S. worked with the G20 to address economic issues such as food insecurity, resulting in a 60 percent increase in annual financing for food and agriculture—now totaling $15 billion. This achievement is concrete. The State Department and White House confirm the U.S. wants a narrow agenda for its 2026 presidency. Major policy groups describe this as an intentional reduction of the prior broader G20 scope. This is not a minor tweak; it signals which problems deserve global cooperation and which do not.

The real effects are measurable. The World Resources Institute reports that when G20 leaders focus on finance and a just transition, they help ensure that the benefits of a low-carbon future are broadly shared and that those most affected have a say. This approach does not end cross-sector work but spotlights green jobs, reskilling, and climate action. Countries that depended on these groups must now negotiate deals alone or in smaller groups. This shift adds complexity, benefits powerful countries, and puts pressure on the treasury and trade departments. UNESCO states that cooperation remains crucial for global education. If international collaboration wanes, its reach and impact decline as well—especially for educational goals. Those working in education and policy need to reassess programs and priorities that assumed ongoing global cooperation. If the G20 ceases to develop joint policies on investment, energy, or training, countries must act. Universities, trade schools, and departments must create their own networks to share knowledge. The Global Governance Project notes that the 2023 New Delhi Summit produced the shortest G20 macroeconomic statement to date, underscoring the need for countries to shape their own economic policies. This narrower focus reduces opportunities for broader learning.

Trump's G20 Plan: From Cutting Environmental Rules to Economic Competition with China

The second change is about priorities. The Trump G20 plan shifts away from environmental, social, and climate issues to focus on the U.S. demonstrating economic power relative to China. Policy papers and experts say the U.S. is returning to finance-first topics and pushing industrial competitiveness. This aligns with other moves: tariffs, trade pressure, promises to bring jobs home, and efforts to achieve industrial independence. The message is clear: deliver economic wins like jobs, investment, and trade advantages to voters. Internationally, this transforms the G20 into a contest of economic strength, not a place for collaboration.

The economic logic is straightforward: when a major country sees a rival growing faster, it can cooperate internationally or use its own tools to compete. The U.S. is choosing the second. Since 2023, it has employed tariffs, exceptions, and targeted incentives, and has treated global meetings as stages for U.S. resolve. IMF data for 2024–25 indicate faster growth in China, highlighting U.S.- China competition. Weak U.S. growth reduces its bargaining power, making short, visible policies more appealing domestically. With a finance-focused G20, the U.S. finds partners for deals that support its supply chains and target threats, rather than agreeing on rules for sustainability or labor.

This plan will face criticism: it ignores global issues such as climate, health, and inequality; it favors powerful economies; and it could fracture global partnerships. There are two counterarguments. First, when growth differences rise, the urge to compete grows, not just as policy but as a response to risk. Second, countries that continue cooperation under limited agendas do so using small, effective solutions, not big statements. The lesson: if the G20 becomes about competition, the work to protect common rules must move into technical groups and national organizations ready to lead.

What Teachers, Leaders, and Policymakers Have to Do About Trump's G20 Plan

If the G20 becomes primarily a platform for countries to display economic strength—and not for collaboration—the impact will extend to education and public institutions. This core argument means education departments and universities must treat G20 developments as tests of relevance for their programs, job training, and research. National groups should (1) focus job training on industrial resilience plus supply chains, (2) expand international research partnerships as global ones become scarce, and (3) ensure trade and investment results are integrated into education. These responses stem directly from the shift in the G20’s role described above: if the group narrows, those affected must act accordingly.

Take these three steps. First, governments should stress-test school and apprenticeship plans for both cooperation and competition scenarios. Second, universities and trade schools should secure industry partnerships to guarantee jobs in sectors such as semiconductors, green tech, and manufacturing, ensuring that promised investments and jobs become real opportunities. Third, use regional organizations to set rules even if G20 collaboration weakens. These steps protect long-term policy learning and job alignment.

Some might say this is too alarmist, or that the U.S. can achieve specific goals without exacerbating global problems. That may be true, but history shows that when major powers focus on short-term economic gains, international cooperation suffers. Economic constraints—rising deficits and financial pressure—limit U.S. international spending and home subsidies in 2025–26. The solution: match budget and economic numbers to what organizations can do. When resources shrink and groups shrink, make cooperation part of decentralized systems that last beyond any one president.

The difference in economic growth between China and the U.S. is more than a figure—it reflects a strategic shift, as U.S. leaders use the G20 as a platform to showcase America's economic direction rather than emphasizing broad worldwide cooperation. According to AP News, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa stated that the G20 has built-in "shock absorbers" to manage disruptions if the U.S. pursues a renewed "America First" approach under a Trump administration. This environment will challenge the adaptability of national education systems, the effectiveness of job training, and the strength of regional partnerships. For teachers and legislators, the advice is clear: stop treating global groups as the only forum for setting rules. Instead, change school programs to focus on supply chains, lock in deals between industry and training groups, and pursue regional technical groups that keep rule-setting alive. If the G20 narrows, we need to expand, not with words, but with organizations that turn summit signals into permanent public benefits.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Brookings Institution. “America’s G20 Opportunity.” Brookings, Jan. 13, 2026.

CFR (Council on Foreign Relations). “The U.S. G20 Presidency: A Narrow Agenda in 2026.” CFR, Dec. 19, 2025.

International Monetary Fund. “World Economic Outlook (October 2025).” IMF Publications, Oct. 14, 2025.

Reuters. “G20 summit in South Africa adopts declaration despite US boycott.” Reuters, Nov. 23, 2025.

U.S. Department of State. “United States Assumes Presidency of the Group of 20.” U.S. State Department release, Dec. 1, 2025.