When Deposits Flip: Rethinking deposit-run risk in a Rising-Rate World

Input

Modified

Deposits can hedge risk, but they can also trigger deposit-run risk Rising rates exposed how fast confidence can turn Regulation must measure deposit fragility, not just volume

In March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank experienced a massive outflow of funds—more than $40 billion in a single day. What had once been the bank's largest asset, its large deposit base, became the reason for its rapid collapse. This revealed a simple but worrisome truth: deposits can act as a buffer during normal times but can also cause problems when times are tough. The main point is this: current rules still treat deposits as a basic sign of stability rather than recognizing that they can change based on factors such as who the depositors are, how many there are, and how quickly they can withdraw their money. If regulators and bank leaders don't pay attention to these details, they might think that a bank is stable just because it has a lot of deposits when it's not. We need to stop merely counting deposits and start measuring how easily a bank could be harmed by a sudden rush of withdrawals. This is because when conditions deteriorate, even small losses can quickly escalate into a significant problem that threatens the bank's ability to remain in business.

Understanding Deposit-Run Risk

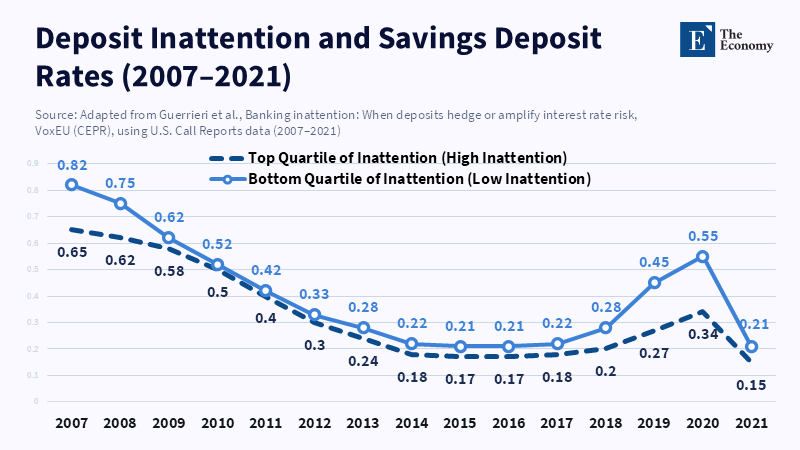

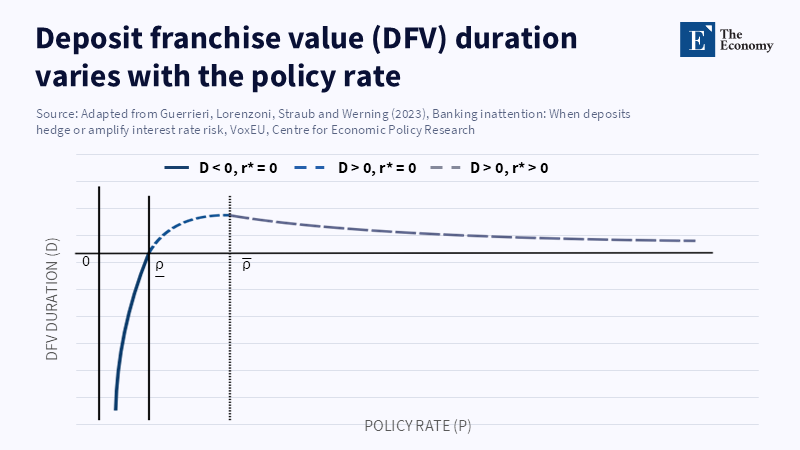

The best way to understand this is through a simple experiment that people in the field use. If deposit interest rates move in lockstep with policy rates, deposits behave like short-term debt and naturally protect a bank from interest-rate risk. But if deposit rates are slow to change, or depositors don't pay attention, then deposits act like cheap, reliable funding. This low-cost funding encourages banks to invest in longer-term assets to increase profits. As market rates rise, the bank begins to incur losses on these long-term investments. These losses aren't a problem as long as depositors leave their money in the bank, but they become apparent when depositors withdraw their money. The key lesson is that the same deposit that protects a bank in one situation can make it more vulnerable in another, depending on depositors' behavior and the details of their accounts.

This difference is important, easy to measure, and concerning. If deposits are concentrated in a few large companies, fintech accounts, or venture-backed businesses, the risk of a single event causing a lot of withdrawals is much greater. With today's fast payment systems, money can be moved out of a bank in hours instead of days or weeks. This means that what used to be a manageable problem—selling assets gradually or using credit lines—can quickly become a crisis where the bank has to sell assets at the worst possible prices. Regulators can use payment-system data and surveys to understand these risks and create plausible scenarios. It's important to treat the different types of deposits as a key element in understanding funding risk.

What Happened in 2022–23: A Shared Test

The rising interest rates in 2022–2023 acted as a real-world test of how fragile deposits can be. A study of euro-area banks found that their unrealized losses on loans and bonds were about 30 percent of their equity. These losses weren't obvious because of how accounting rules work, but they still made the banks more vulnerable. The euro-area banks were able to withstand the pressure because they had shorter-term assets, used interest-rate swaps, and had a more diverse mix of deposits compared to U.S. banks. So, the system avoided a widespread crisis not because the banks were strong but because they had different ways of protecting themselves and different types of deposits.

The U.S. situation showed how quickly things can go wrong. A bank with a concentrated depositor base, a lot of uninsured deposits, and long-term securities is at risk. If the bank's value goes down, it signals that the bank is in trouble. If this is announced publicly, or if the bank seeks to raise capital, depositors might become concerned and withdraw their money quickly. If the bank runs out of liquid assets, it can become insolvent. Silicon Valley Bank's rapid collapse shows that how a bank is managed and how it protects itself are just as important as the overall economic conditions. The risk of contagion—where one bank's failure makes others appear more fragile—is real, especially when there are many uninsured deposits and negative news spreads quickly.

Changing the Policy Discussion

If deposit fragility is a major factor, then regulations need to change. Liquidity Coverage Ratios and Net Stable Funding Ratios are still useful, but they are not precise enough. These rules group deposits into categories and set buffer levels based on size rather than on how likely depositors are to withdraw their money. A better approach is to add scenarios that consider how depositors might behave in different situations. Regulators should account for situations in which 5–10 percent of uninsured deposits are withdrawn within 24–72 hours due to realistic events, such as a fintech payout being paused, a shock to a particular industry, or companies moving their money to other banks. This would change stress tests from general exercises to specific probes that show the risk of sudden insolvency.

This change has three practical results. First, capital and liquidity requirements should be based on measured fragility indicators—like concentration ratios, the share of uninsured deposits, and platform exposure—not just on asset size. Second, banks should be required to maintain withdrawal maps that list their large depositors, their connections to the bank, and the likelihood that they will withdraw their funds in specific situations. Third, resolution plans should be designed to provide targeted, quick support for specific runs, rather than broad, system-wide guarantees that create moral hazard.

Practical Steps for Banks, Educators, and Policymakers

Bank risk teams should immediately begin mapping deposits by owner type, concentration, and behavior—such as retail, corporate, fintech, and sweep accounts—and compare this map against the bank's asset-side duration profile. They should run scenarios that combine valuation shocks with withdrawal events and measure the results at 24, 72, and 168 hours. These scenarios should be linked to governance triggers so that predefined actions—such as collateral calls, hedging adjustments, and communication procedures—are triggered automatically when thresholds are crossed. This requires allocating resources to data and staff who understand behavioral models, but the investment is small relative to the cost of a failure. International cooperation can standardize templates and reduce informational problems. Regulators often have confidential data that can be used to calibrate scenarios and identify banks with high behavioral exposures.

Educators should update their courses to teach deposit heterogeneity as a key concept. They should use recent events as case studies, run withdrawal map exercises, and emphasize how concentration interacts with payment convenience. They should also have students consider the trade-offs among deposit price, duration, and the probability of behavioral migration. Policymakers should require supervisory withdrawal mapping and set add-ons for uninsured concentration. This method avoids penalizing all deposit funding and instead focuses on the risks. It preserves the benefits of deposit funding for diversified retail banks while making fragile funding mixes more expensive.

In conclusion, deposits are not inherently safe or dangerous. Their stability depends on the identity, number, and behavior of the depositors. The events of 2022–2023 demonstrated that losses on long-dated assets can quickly translate into funding shortfalls when deposit fragility is high. The solution is to stop treating deposit amounts as a proxy for strength and to measure fragility directly. Regulators should require withdrawal maps and the conduct of behaviorally calibrated stress tests. Banks should understand fragility through funding-mix governance and scenario-triggered playbooks. According to the OECD, advancing international cooperation on data standards can improve outcomes in the financial sector, making it valuable for teachers to emphasize concepts such as deposit heterogeneity and the importance of coordinated run-scenario planning. These tools are doable, affordable, and can be used immediately by regulators and banks.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2023) Report on the 2023 banking turmoil. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2023) Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank. Washington, DC: Federal Reserve Board.

European Central Bank (2024) Keep calm, but watch the outliers: deposit flows in recent crisis episodes. Occasional Paper No. 361. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

Guerrieri, V., Lorenzoni, G., Straub, L. and Werning, I. (2023) ‘Banking inattention: When deposits hedge or amplify interest rate risk’, VoxEU Column, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Rice, J. and Guerrini, G.M. (2025) Riding the rate wave: Interest rate and run risks in euro area banks during the 2022–2023 monetary cycle. Working Paper No. 3090. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

Schnabel, I. (2023) ‘Interest rate and deposit run risk: New evidence from euro area banks during the 2022–2023 tightening cycle’, VoxEU Column, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Bank Policy Institute (2024) Nelson, W. ‘Deposit and interest-rate risk: Some simple but surprising results’. Washington, DC: Bank Policy Institute.