[Physical AI] AI Begins to Acquire a Body — The Starting Point of Innovation or a Collection of Challenges

Input

Modified

Nvidia’s next core challenge: physical AI

Actual executable tasks remain limited

Labor resistance and workplace anxiety surface

Jensen Huang’s recent remarks have pushed “physical artificial intelligence (AI)” to the center of the technology discourse. Declaring that AI has entered a stage in which it understands and actively acts in the real world, Huang clearly positioned the transition to robotics as the next inflection point. The prevailing interpretation, however, is that this shift represents not the immediate replacement of human labor, but rather AI’s expansion into the physical domain. A wide range of challenges remain unresolved, spanning technological maturity, cost structures, supply chains, and social acceptance. The era of robots may be at the threshold, but the speed and direction of its spread remain undecided.

AI enters the physical world

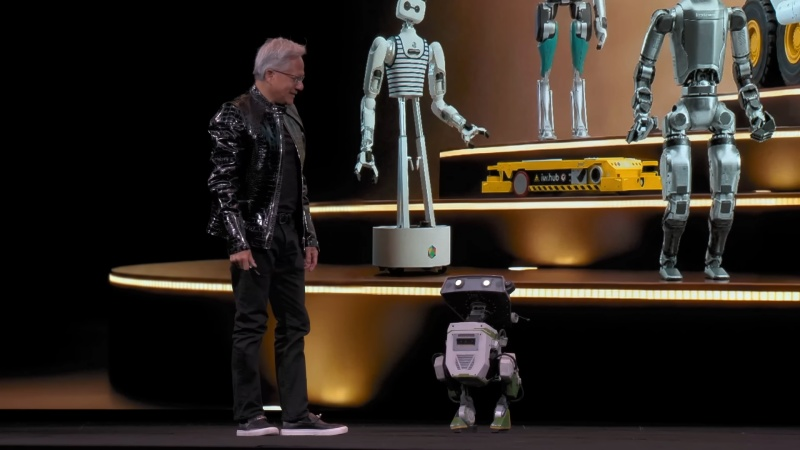

Debate across the global tech industry over the potential of physical AI has intensified in recent weeks. The catalyst was a statement by Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang. Appearing as a keynote speaker at CES 2026, the world’s largest electronics trade show held early last month, Huang stated that “machines have begun to understand, reason about, and act in the real world.” The message was that AI has moved beyond software to exert tangible influence in the hardware domain. Through this statement, Huang made clear that the next stage of AI development lies in automating judgment and action grounded in the physical world.

Building on this view, Huang unveiled a suite of new open physical AI models and frameworks, along with an infrastructure strategy designed to support them. “The ‘ChatGPT moment’ has arrived for robotics as well,” he said, emphasizing that the emergence of physical AI models enables entirely new applications. He pointed in particular to Nvidia’s full-stack approach—combining Jetson robotics processors, CUDA, Omniverse, and open physical AI models—and argued that, through a global partner ecosystem, this stack could significantly raise automation levels across industries. The move signals Nvidia’s intent to position physical AI as a general-purpose platform integrating semiconductors, software, and simulation.

A number of on-site examples underscored this perception. Samsung Electronics presented robots as a future core growth engine, outlining application pathways from manufacturing floors to households. Hyundai Motor showcased the humanoid robot Atlas and the quadruped robot Spot, developed in collaboration with Boston Dynamics. LG Electronics, meanwhile, introduced integrated usage scenarios combining AI appliances and robotics through its home robot “Cloid.” All of these cases pointed toward an evolution into comprehensive platforms that merge sensors, AI, and control systems.

World-model-based technologies unveiled by Nvidia—including Isaac GR00T, Cosmos Reason, and Cosmos Transfer—were presented in the same context. These technologies were introduced as core components that allow robots to learn the physical laws of the real world and plan actions through simulation. Within the industry, this has fueled the view that the center of AI competition is shifting from large language model (LLM)-based services to physical AI capable of understanding the physical world. Huang’s remarks are thus seen less as a claim about technical completeness in a specific field and more as a signal indicating where the center of gravity in the AI industry is moving.

Technology still “in progress,” mass adoption uncertain

Even so, it would be premature to interpret these discussions as evidence that physical AI has reached technological maturity. Huang’s message is widely viewed as a presentation of the next challenge for AI development rather than an announcement of robots ready to immediately replace human labor. In practice, most currently unveiled humanoid and industrial robots perform reliably only in controlled environments and repetitive tasks, while still requiring human intervention in complex judgment or exception handling. Across the industry, physical AI is regarded as a high-difficulty domain that simultaneously demands advances in sensing, control, mechanical design, and data accumulation.

Technical limitations are also evident in practical use cases. Many robots approaching commercial deployment are optimized for specific processes, and their performance often degrades sharply when operating conditions change. World-model-based reasoning has been proposed as a countermeasure, but fully reproducing the physical laws and variables of the real world through simulation alone remains difficult. What industrial sites actually require—robust safety across diverse situations and continuous learning capability—remains an unresolved challenge.

High prices represent another major barrier to commercialization. At the current stage, humanoid robots and high-performance industrial robots carry high component and system integration costs, making investment decisions aimed at large-scale deployment difficult. Key components such as actuators, sensors, and control modules remain expensive, and limited production volumes constrain cost reductions. As a result, the focus of the global robotics industry is increasingly shifting from “who can build the most sophisticated robot” to “who can mass-produce robots more cheaply and reliably.”

In this context, the mass adoption of physical AI is unlikely to be determined by technological achievement alone. Analysts note that widespread deployment requires the simultaneous alignment of technological maturity, cost structures, supply-chain stability, and the pace at which industries and societies can absorb change. At present, physical AI presents clear expectations for industry, while also exposing equally clear real-world barriers. This is why forecasts increasingly suggest that, rather than radically transforming workplaces in the short term, the technology will expand its application gradually within limited domains.

Labor, institutions, and the challenge of social consensus

Resistance from the labor front is another critical issue. In Korea, the case of Hyundai Motor’s labor union stands out. The humanoid robot Atlas unveiled at CES 2026 and the unmanned autonomous factory project “DF247” based on it have become focal points of controversy. The union has expressed concern that production could be shifted to overseas plants where robot deployment is feasible, potentially leaving domestic facilities idle, and has stated that “robot deployment without labor–management agreement is unacceptable.” The lack of clear provisions regarding the roles and protections of existing workers after automation has been cited as a key problem.

Some observers have likened these developments to a “21st-century Luddite movement.” The comparison recalls historical resistance by workers to mechanization during the early Industrial Revolution, which ultimately led to institutional reform and social compromise. At the time, workers forcefully expressed fears that rapid changes in production methods threatened their livelihoods. In this sense, today’s debates over robots and AI extend beyond questions of technological merit to the issue of who bears the cost of transition. Resistance from labor is increasingly viewed less as an attempt to reverse technological progress than as a challenge to how that transition is managed.

This has also highlighted the role of policymakers and society at large. President Lee Jae-myung addressed the issue directly on the 30th of last month at a National Startup Era Strategy Meeting held at the presidential office, referencing the conflict between Hyundai Motor and its union. He stated that “there are clear limits to creating ‘ordinary, good jobs’ through traditional methods,” adding that “there is no answer in trying to roll back robot adoption.” He further observed that “the era in which acquiring ordinary skills and securing an ordinary job naturally guaranteed retirement and livelihood has come to an end.” His remarks underscore the idea that how organizations and society respond to change will shape the future structure of industry and the labor market.

Comment