China Seeks Trilateral Swap with Korea, Japan to Bolster Yuan Amid U.S. Pressure

Input

Modified

SCMP: China in Talks with South Korea and Japan on Possible Trilateral Currency Swap Amid Trump-Era Tariff Threats, Beijing Seeks to Bolster Financial Stability Focus on Whether Japan, a Quasi-Reserve Currency Nation, Will Agree to China’s Proposal

China is reportedly in discussions with South Korea and Japan over the possibility of establishing a trilateral currency swap agreement. The three countries have all suffered export setbacks amid U.S. tariffs imposed under the Trump administration, and the move appears aimed at strengthening regional financial cooperation in East Asia. Markets are closely watching how Japan, a quasi-reserve currency nation, will respond and what other variables may shape the outcome.

Could East Asia’s Three Economies Turn Cooperation into Reality?

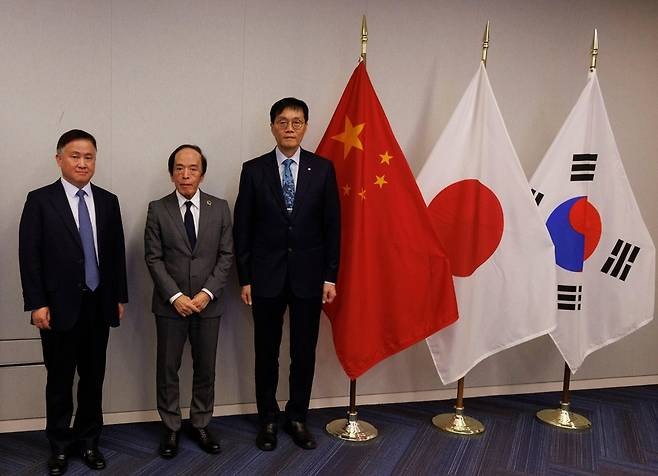

According to a report by the South China Morning Post (SCMP) on October 22 (local time), citing unnamed sources, China is in talks with South Korea and Japan on the possibility of establishing a trilateral currency swap arrangement. Pan Gongsheng, Governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), reportedly discussed the issue last week in Washington on the sidelines of the IMF–World Bank Annual Meetings with his counterparts — Rhee Chang-yong of the Bank of Korea and Kazuo Ueda of the Bank of Japan.

South Korea already has bilateral currency swap agreements with both countries. The Korea–China swap was first signed in 2002 for 2 billion dollars, later expanded to 4 billion dollars in 2005, 30 billion dollars in 2008, and 56 billion dollars in 2011. Although negotiations were strained in 2017 due to tensions over the THAAD missile defense deployment, the swap was renewed for another three years at the same scale. In 2020, the two nations expanded it again to 59 billion dollars and extended the term from three to five years. That agreement expired this month.

Meanwhile, South Korea and Japan entered into a dollar-based swap arrangement in 2023. Unlike conventional swaps involving direct currency exchanges, a dollar swap uses the U.S. dollar as an intermediary. If Korea lends won, Japan provides dollars, and vice versa if Japan lends yen. Given the continued depreciation of the yen, the move effectively served as a safeguard for Japan’s currency stability. When Japan lends yen to Korea and receives dollars in return, domestic dollar supply rises while yen liquidity contracts, helping to curb further yen depreciation against the dollar.

Why Did China Play the Currency Swap Card?

China’s outreach to both South Korea and Japan—beyond simply renewing its existing swap deal with Seoul—appears to be part of a broader strategy to expand the use of the yuan overseas and reduce dependence on the U.S. dollar. As of the end of last month, China had swap agreements with 32 central banks worldwide, with a combined total of about 4.5 trillion yuan (roughly 625 billion dollars), underscoring the currency’s growing global footprint.

Experts share a similar view. One international finance analyst noted, “With all three economies facing export headwinds from U.S. tariffs, strengthening regional financial cooperation is a natural move. It also aligns with China’s goal of promoting yuan internationalization by reducing dollar reliance and expanding local-currency settlements.”

Still, the structure of a potential China–Korea–Japan arrangement remains uncertain, as does whether it would fall under the Chiang Mai Initiative—a multilateral swap framework established in May 2000 among 10 Southeast Asian nations and their partners. Further discussions are expected at the upcoming ASEAN and APEC summits.

The Fundamental Barrier to Currency Swap Agreements

Attention is now on whether Japan, as a quasi-reserve currency nation, will readily respond to China’s proposal for a trilateral swap. Countries with currencies that already carry strong international credibility have little need to extend further credit through swap lines. This means they tend to be selective and cautious about their swap partners and terms. The same tendency was evident when the United States recently showed reluctance toward South Korea’s request for a new swap line.

In July, South Korea and the U.S. reached a verbal understanding to lower U.S. tariffs on Korean goods in exchange for Korea implementing measures such as a 350 billion–dollar investment in the U.S. However, the trade arrangement has not yet been formalized in writing, as Korea’s foreign reserves remain limited for a large cash investment. As of the end of last year, Korea’s nominal GDP stood at 1.87 trillion dollars, while its foreign exchange reserves totaled 416 billion dollars—only 22.2% of GDP, noticeably lower than that of other major Asian economies.

For that reason, Seoul proposed an “unlimited currency swap” as a prerequisite for the investment plan. Washington, however, reportedly insisted on what it described as a “blank-check commitment,” citing its previous arrangement with Japan. The gap in positions between the two countries remains wide. On October 16, National Security Advisor Wi Sung-lac stated, “There has been little progress in the swap discussions. Korea proposed it, and the U.S. reviewed it, but it was not accepted.” He added that even if a swap deal were reached, it would be only a “necessary condition,” emphasizing that additional “sufficient conditions” must be met and that the government does not place high expectations on a Treasury-led swap agreement.

Comment