Korea’s Silence, China’s Surge: Will OLED Replay the LCD Nightmare?

Input

Modified

Backed by state subsidies, BOE and TCL expand aggressively

“Technology gap is narrowing,” say industry insiders

Japan’s lesson: productivity without innovation leads to decline

As the organic light-emitting diode (OLED) market rapidly expands around IT devices, the competition for dominance between Korea and China is intensifying. While Korean firms have scaled back investment to catch their breath, China is moving to replicate the same strategy that once dethroned Korea in the liquid crystal display (LCD) market—using massive state support and profits from its LCD monopoly to finance new OLED production lines. Experts warn that leadership in OLED “will hinge more on the speed of decision-making than on technology itself,” cautioning that continued investment stagnation could push Korea down the same path of decline once taken by Japan.

China accelerates expansion despite oversupply concerns

According to market researcher Omdia, China appears intent on replaying its LCD playbook in the OLED sector. Presenting at the Korea Display Conference in Seoul, Omdia said China’s aggressive investment in IT-use OLED, fueled by huge government subsidies and LCD profits, could again lead to market domination. With smartphone OLEDs nearing maturity and TV OLED growth slowing, the next battleground has become OLEDs for laptops and tablets.

China has zeroed in on eighth-and-a-half-generation (Gen 8.6) production lines, which use 2,250×2,600 mm glass substrates offering far greater efficiency than Gen 6 panels. In Korea, only Samsung Display is investing—targeting mass production of 15,000 sheets per month early next year. In contrast, four Chinese firms—BOE, CSOT, Visionox, and Tianma—have all announced Gen 8.6 lines. Omdia forecasts that China will hold 64 percent of global Gen 8.6 IT OLED capacity by 2028 and 70 percent by 2030, signaling that production capacity may soon determine market control.

This advantage stems from the combination of LCD-generated cash flow and government support. China already dominates 70 percent of global TV panel and 68 percent of monitor panel output. Profits from that near-monopoly are being recycled into OLED, while subsidies further fuel expansion. This “low price + high volume” model allows companies to keep building even while operating at a loss—receiving additional subsidies for maintaining certain utilization rates. As a result, even if technical gaps remain, cost and scale advantages quickly close the distance.

Market forecasts also tilt in China’s favor. Omdia projects the global display market will grow about 4 percent in sales by 2026, with OLEDs up 8 percent. However, with BOE, Visionox, and CSOT leading Gen 8.6 investments, oversupply could hit as early as 2029, just four years after market expansion begins. In that cycle, price pressure will intensify, giving China further incentive to use subsidies and scale to boost its share. BOE already has Gen 8.5 TV experience, and CSOT has produced 65-inch inkjet samples. Korean firms now face pressure on both IT and TV fronts.

Investment pause leaves Korea exposed

China’s technology catch-up is also accelerating. Omdia’s Park Jin-han said, “China is on track to overtake Korea in Gen 8.6 IT OLED by 2028.” While Korea still holds 69 percent of the overall OLED market, the fast-growing 8.6G segment tells a different story. At a National Assembly policy forum last month, experts warned that the current investment gap could translate into an apparent technology gap within two to three years. The message: success depends not only on technical prowess but on mass-production timing, capacity, and demand alignment.

The numbers are revealing. In Korea, Samsung Display alone runs a Gen 8.6 line at its Asan plant, producing about 15,000 sheets monthly. It plans to begin mass production this year, supplying OLED panels for Apple’s MacBook Pro. Meanwhile, BOE is building a Gen 8.6 OLED plant in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, and is pushing to advance its mass-production schedule to early next year—despite delayed orders—accepting initial yield risks to narrow the technology gap. Such a move could quickly erode Korea’s early lead and accelerate China’s capacity dominance.

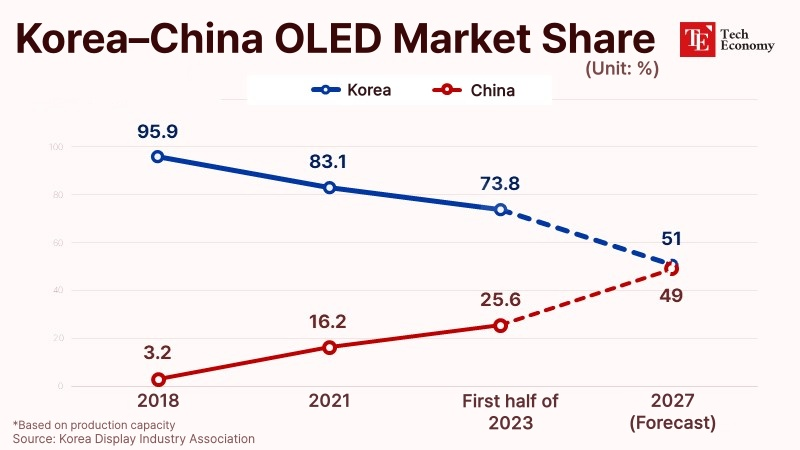

The shift is already visible in market share data. According to the Korea Display Industry Association, China’s OLED market share is expected to surge to 49 percent by 2027, nearly matching Korea’s 51 percent. The gap, once nearly 50 percentage points in early 2023, is closing at a remarkable pace. Meanwhile, Chinese smartphone makers such as Huawei, Oppo, and Vivo have slashed their use of Korean OLED panels—from 78 percent in 2021 to just 16 percent in 2024. Many analysts now warn that Korea’s OLED industry is slipping into the same structural disadvantage it faced during the LCD era.

Japan’s fall offers a sobering warning

Experts emphasize that industry leadership depends on speed of execution, not technology alone—pointing to Japan’s downfall as a cautionary tale. In the late 1990s, Japan still led global display technology but lost ground to Korea by lagging in production efficiency and investment timing. Sharp built a 10th-generation LCD line early, but Sony, seeking to cut costs, sourced panels from Samsung instead. Samsung, in turn, adopted LED backlighting over CCFL, pioneering the “LED TV” category just as high energy prices and efficiency trends swept the world—propelling Korea to the center of the market.

From there, Japan’s industrial collapse was rapid. As LCD demand shifted to Korea, Japanese component and materials suppliers saw their ecosystems crumble. Companies like Japan Display (JDI) attempted to pivot to OLED but failed to secure mass-production footing, effectively exiting the business. Despite recognizing OLED as the next frontier, Japan’s government and private investment were out of sync, while Korea, China, and Taiwan poured in massive capital and captured the market’s growth.

Today, Korea’s display industry faces similar conditions. China leverages subsidies and lower labor costs to cut production expenses by more than half, while Korean firms, burdened by profitability concerns, delay new investment. The same structural pattern that once doomed Japan—falling behind not in technology but in market timing—is reemerging. Experts agree that technological sophistication alone cannot sustain industrial leadership; only a coordinated strategy linking investment, production, and demand can prevent Korea from repeating Japan’s fate.