Fed Cuts Rates by 0.25% Amid Labor Market Slump, but December Move Remains Unclear

Input

Modified

ed Cuts Rates at October FOMC Amid Internal Divisions Weakening U.S. Job Data Sparks Fears of a “Stall Speed” Slowdown “Labor Demand and Supply Are Both Declining,” Fed Warns

The U.S. Federal Reserve decided to cut its benchmark interest rate at the October Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting. The move is seen as a preemptive step to counter an economic downturn amid clear signs of weakening in the U.S. labor market.

Further Rate Cuts This Year Remain Uncertain

On the 29th (local time), the Federal Reserve announced after its FOMC meeting that it would lower the federal funds rate target range by 0.25 percentage points to 3.75–4.00%. The Fed also said it would end its balance sheet reduction program (quantitative tightening) effective December 1.

At a press conference, Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted, “There was significant divergence of views among committee members,” adding, “While markets appear to be pricing in another rate cut in December, that is not a given.” During the meeting, Kansas City Fed President Jeffrey Schmid argued for holding rates steady, while Governor Steven Miran called for a larger 0.5-point cut — underscoring internal divisions within the Fed.

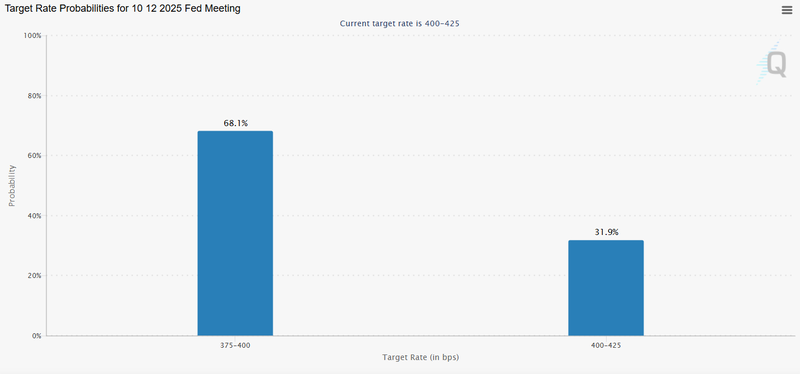

Powell’s remarks were interpreted as a hawkish signal, heightening market caution. According to CME’s FedWatch tool, the probability of another rate cut in December dropped from 91% to 68.1% following Powell’s comments, while the likelihood of holding rates steady rose to 31.9%. Expectations for a 0.5-point cut fell to zero. The FedWatch tool reflects market expectations for future U.S. interest rates based on federal funds futures trading in New York.

U.S. Employment Risks Surge

The Federal Reserve’s rate cut this month was aimed at countering a slowing economy and growing labor market risks. Over the past six months, core nonfarm employment growth in the U.S.—excluding government and healthcare sectors—has effectively flattened to zero. This indicator is considered one of the key gauges of the U.S. business cycle; historically, every time it bottomed out over the past 60 years, a recession followed.

Dario Perkins, a macroeconomist at U.K.-based research firm TS Lombard, posted a chart of core nonfarm job growth on X (formerly Twitter) on the 1st, writing, “This is the chart that terrifies the Fed. They firmly believe in the ‘stall speed’ theory.” The term “stall speed,” borrowed from aviation, describes the point at which an aircraft loses lift and begins to descend without power. In economic terms, it refers to an economy slowing so sharply that it enters a powerless descent—approaching recession without sufficient policy “thrust” to maintain growth.

Peter Berezin, chief global strategist at BCA Research, echoed this concern in an interview with Business Insider last month, saying, “The U.S. labor market is on the verge of stall speed. It’s becoming too weak, and consumers are now cutting back on spending.” He explained, “When people grow anxious, they spend less. When they see friends or family members losing jobs, they pull back even more. This cycle reinforces itself.” Berezin estimated that if the U.S. economy enters a stall-speed phase, the unemployment rate—currently at 4.2%—could surge to as high as 6%.

What’s Behind the Weakening U.S. Labor Data?

Some analysts argue that the deterioration in employment indicators stems more from a decline in labor supply—driven by reduced immigration—than from weakening labor demand by businesses. In other words, the labor market may not yet be facing a full-scale downturn. According to a report released on the 24th by the Bank of Korea’s U.S.–Europe Economic Team, titled “Causes of the U.S. Employment Slowdown and Assessment of the Current Labor Market,” about 45% of this year’s employment decline in the U.S. resulted from reduced labor supply due to falling immigration. The report also noted that with net immigration currently hovering around 60,000, the likelihood of a further sharp drop in immigrant labor is low.

The Federal Reserve, however, believes that both slowing demand and reduced supply are weighing on the job market. In his opening remarks at the FOMC meeting on the 29th, Chair Jerome Powell stated, “While the unemployment rate remained relatively low through August, job growth has slowed noticeably since early this year.”

He added, “Much of this slowdown appears to reflect reduced labor supply due to lower immigration and participation, but labor demand has also clearly weakened.” Powell continued, “Even though the release of September’s official employment data has been delayed by the government shutdown, available information shows both layoffs and hiring remain subdued. Households are sensing fewer job opportunities, and businesses report that hiring difficulties have eased.” He emphasized that “labor market dynamism has declined somewhat and weakened recently, with downside risks to employment increasing in recent months,” noting that these developments “have shifted the balance of risks.”

Comment