Crowded Out: How Trade Diversion Rewires Education and Opportunity

Input

Modified

Tariffs do not just redirect trade; they quietly reroute skills, students, and institutions Trade diversion reshapes education and jobs Policy must treat trade shocks as human-capital shocks, not only as economic ones.

When the U.S. decided to increase tariffs on a range of Indian goods to roughly 50% in 2025, it didn't just make those products more expensive. It caused a ripple effect, changing where businesses and people put their money and energy. This is trade diversion – when trade and investment shift away from one country towards others. We saw this happen quickly in trade talks, company hiring plans, and even what students chose to study. Businesses that used to sell mainly to American customers started looking to Europe and other big markets instead. Universities noticed that the demand for specific skills was changing. Training programs either lost their relevance or found new areas to focus on. So, tariffs stopped being just a simple tax issue and turned into a constant influence, reshaping where talent develops and which schools and organizations succeed. The key takeaway for educators and government officials is that trade diversion harms human capital. If we see it only as a tariff problem, we miss how it changes who learns what, who gets hired, and where career opportunities arise.

Trade Diversion Reshapes Who Works With Whom

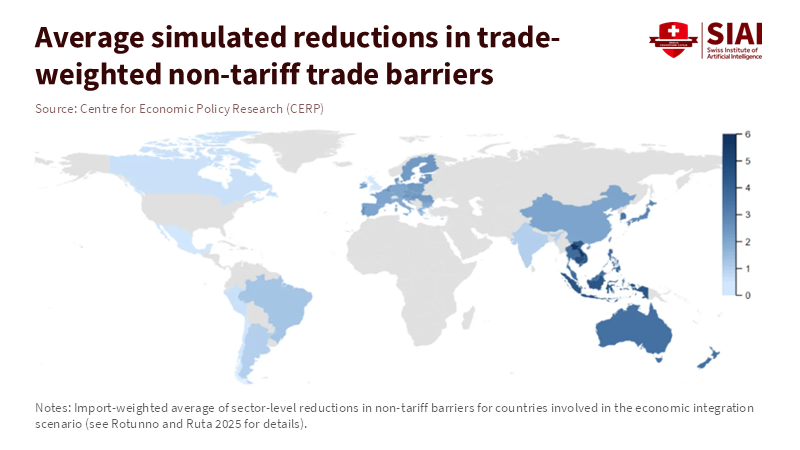

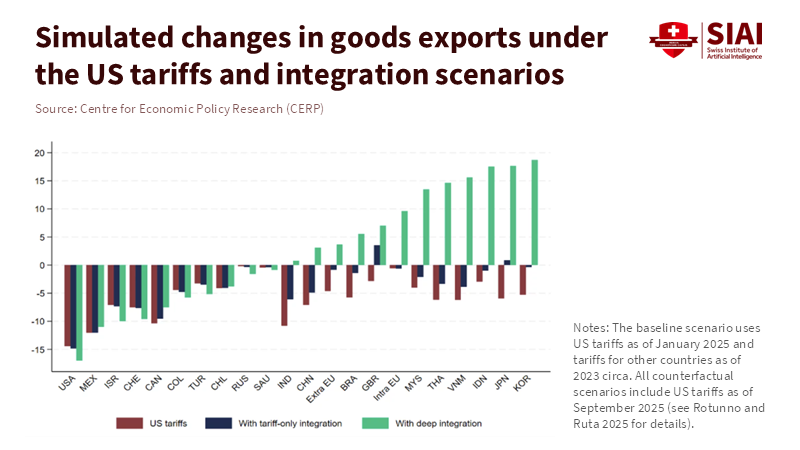

When a major buyer like the U.S. significantly raises its trade costs, sellers naturally look for new customers. This simple market reaction has a domino effect on international partnerships. As U.S. trade barriers rose between 2024 and 2026, India began working more closely with the European Union and its neighbors. Stalled negotiations suddenly became urgent, and new agreements unlocked opportunities not just for goods but also for services, people movement, and investment. These new pathways are important for students and educational institutions. Companies that moved their sales to the EU needed staff who understood European standards, procurement rules, and regulatory requirements. They started posting different internships and changing their hiring preferences for graduates. Career services offices felt the change right away, as the number of jobs aimed at the old market decreased and new jobs appeared for the new markets.

These changes even affect where research and development, labs, and apprenticeships are located. When companies move their purchasing and some of their assembly operations, they often move training and internships closer to their new customers or to areas with the relevant standards. Local industries built to serve U.S. customers can lose business and the private funding that supports graduate students and lab technicians. Universities then face two challenges: maintaining their core research capabilities, which are funded by long-term partnerships, and building flexible connections with new buyers. The best response is to combine short-term solutions with long-term strategies that make skills transferable – things like certificates that can be used in different situations, international internships, and agreements between countries that allow students to transfer their qualifications between markets.

Politically, this shift changes who has the upper hand in negotiations. State and national governments compete to attract redirected orders. This competition can attract new investment and new branches from multinational companies. It can also create incentives that trap a region into relying on just one set of partners. To manage this risk, government policy should support people through the transition while ensuring that incentives promote skills that can be used across different jobs and locations. In practice, this means funding short retraining programs, setting job placement goals for public funding, and negotiating trade deals that include practical provisions on mobility and training. Think of diplomacy as the first step, and education as the bridge that turns new market access into stable jobs.

Trade Diversion Pushes Out People, Businesses, and Countries

Trade diversion works through a simple chain of events: buyers switch orders, producers move resources or finishing operations, capital follows contracts, and workers chase the jobs. This chain leads to crowding out. Countries and regions that lose buyers see businesses shrink or move away. Small suppliers that depended on a single buyer find their opportunities disappearing. Students who trained for the old needs see fewer job openings. Research on major tariff events consistently shows this pattern. Studies of company exports show a quick shift of shipments to other countries. Central banks and international organizations that model the effects of recent tariffs report significant trade diversion and some losses in global production. The scale varies by industry, but the impact on people is consistent: where the markets go, people follow.

For education systems, the crowding out is immediate and easy to see. Course programs that are closely tied to a specific buyer's technology or standards suddenly become less valuable. Specialized labs that train students using equipment specific to one employer see fewer job placements. Partnerships that offer internships and co-op positions may disappear when companies move their purchasing networks. These shifts aren't just economic; they change people's life choices. A graduate who expected to find a local job with a stable employer must now decide whether to retrain, move, or accept a lower salary. Government responses that only support struggling industries risk protecting outdated skills and slowing necessary mobility.

Small and medium-sized businesses face the most significant challenges. Large international companies can relocate and rebrand relatively easily, but smaller suppliers can't. They lose access to informal training opportunities and the valuable on-the-job learning that comes with long-term contracts. This weakens regional training systems. policy must be collective and practical: shared apprenticeship funds, shared technical facilities, and regional career centers that connect displaced learners with the new customer base. These actions reduce the crowding-out effect and protect the skills that support future growth.

Trade Diversion Can Be Reversed: Policy Tools for Education and Labor

If trade diversion pushes people and businesses out, policy can lessen and reverse those effects. Three tools are important for educators and government officials. First, diversify partnerships. Don't rely on just one market or a few buyers. Create pathways to multiple markets, so students have alternative job options. Second, make qualifications transferable. Certificates that can be used across different situations, short diplomas, and precise skill mappings accelerate transitions and enable learners to demonstrate their skills to new customers. Third, include protections for human capital in trade talks. Mobility, reciprocal recognition of certificates, and joint training programs must be part of the negotiations, not an afterthought.

These tools are practical. A university can issue a certificate that can be used in various situations with employers within six months. Governments can negotiate side agreements to mutually accept short-term certificates. Rapid retraining funds can help cover wages while graduates retrain for industries connected to new buyers. Research shows that active labor-market programs reduce long-term earnings losses when workers are retrained quickly and connected to job openings. To make this work, design funding to be performance-based. Connect grants to job placement results. Require data sharing between companies and training providers so that courses reflect real hiring needs.

Governance and the private sector are also important. Research grants may depend on local hiring commitments. Industry groups can pool funds for shared labs and regional apprenticeships. Trade associations can promote international recognition of short-term qualifications. These steps make the system strong. They turn trade deals into ongoing learning partnerships and ensure that new market access leads to jobs, not just tariff reductions.

A simple checklist for institutions helps turn these ideas into action. Review employer demand every three months. Begin a certificate program that can be used in different situations within six months. Negotiate one recognition agreement in the next round of trade talks. Fund a pilot program to rapidly retrain displaced groups. Create a regional career center that shares job placement data with local companies. Set measurable job placement goals and publish the results. These items don't cost much, but they have a significant impact.

Treat Tariffs as a Human Capital Issue

A 50% tariff is more than simply a tax shock. It's a force that reassigns customers, shifts capital, and changes which skills are important. Educators, along with policymakers, should change their strategy accordingly. Tariffs should be seen as much a part of human capital policy as they are of trade policy. Create qualifications that can be used in different situations and locations. Partnership employer relationships. Add mobility and recognition clauses to trade agreements—fund rapid retraining for groups affected by market changes. Connect research support to local hiring outcomes. These actions keep students connected to opportunities and reduce the social cost of trade adjustments.

The last point is essential. When markets change, people go through that change. A policy that treats those people as inactive spectators will fail. A policy that treats learning and trade as two sides of the same strategy will protect jobs, maintain research capacity, and keep regions strong. Trade diversion can serve as a force for renewal if it's combined with an education policy that is quick, transferable, and measurable. If not, it will quietly push entire groups of people out of the markets that the world needs.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

CEPR. 2026. US tariffs may deepen integration, elsewhere. Centre for Economic Policy Research (VoxEU) column.

Chatham House. 2025. Trump’s tariffs put strain on US–India ties, but relations will endure in the long run. Expert comment.

Indian Express. 2026. Trump’s 50% India tariffs: Full timeline of trade tensions and US–India relations. News article.

LSE CEP. 2025. Trade diversion and labor market outcomes. Centre for Economic Performance, Discussion Paper.

Reuters. 2026. Trump’s tariff cut sparks relief in India despite scant details; and India to sign trade deal with United States in March, minister says. News reports on tariff adjustments and trade negotiations.

RIETI. 2025. Economic impact of U.S. tariff hikes: Significance of trade diversion. Research report.

Comment