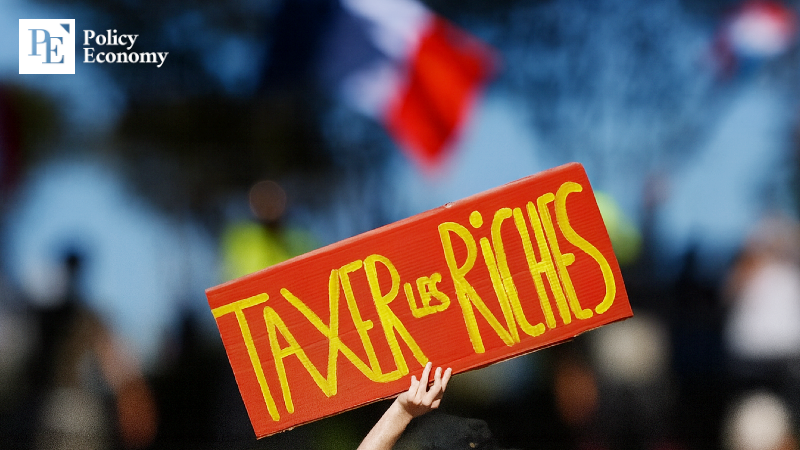

“Time for the Richest to Pay Up” — France Engulfed by Self-Serving Economics

Input

Modified

Fiscal Addiction Triggers Nationwide Protests Citizens Oppose Austerity Despite Soaring Deficits Public Unites Behind Wealth Tax on the Super-Rich

French society is once again ablaze with an age-old debate over taxing the rich, after Bernard Arnault, the chairman and chief executive of LVMH, the world’s largest luxury conglomerate, amassed an additional $19 billion in a single day — a surge equivalent to $26 billion. The company’s surprise earnings report sent its share price soaring, causing Arnault’s net worth to balloon to astronomical levels and igniting France’s renewed discussion over a wealth tax. The proposal, championed by French economist Gabriel Zucman, seeks to fill the fiscal gap created by soaring public debt and widening deficits through a so-called “Zucman Tax.” The plan would impose a 2% levy on assets exceeding $110 million, ostensibly to correct inequality. Critics, however, warn that such a tax would cripple business incentives and drive capital out of the country.

Arnault’s $19 Billion Wealth Surge Rekindles Wealth-Tax Debate

According to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index on the 15th (local time), Arnault’s personal fortune jumped $19 billion in a single day, reaching $192 billion in total — his second-largest daily gain ever. The spike was fueled by LVMH’s stock rally, which soared 12% after the group reported third-quarter earnings that far exceeded market expectations. Its flagship fashion and leather goods division posted robust growth, driving the surge.

LVMH’s strong performance sparked fresh optimism across the industry, propelling shares of other French luxury houses such as Hermès International (+7.35%) and Kering, the parent company of Gucci (+4.77%). The rally marked the strongest growth since the pandemic era, underscoring how a small circle of French dynasties continues to dominate the global luxury sector.

But this prosperity has collided head-on with mounting political tensions at home. France is grappling with delayed budget approvals, widespread protests against labor reforms, and plummeting approval ratings for the government. Compounding the turmoil is a worsening fiscal crisis: by the end of the second quarter, France’s public debt reached $3.7 trillion, equivalent to 115.6% of GDP — far exceeding the EU average of 81%, and trailing only Greece and Italy among eurozone economies.

The government’s attempt to rein in the ballooning debt through austerity measures quickly collapsed under massive strikes and demonstrations. To a populace convinced that reckless spending and tax cuts for the wealthy caused the debt crisis, austerity represents an unfair imposition of sacrifice. Outrage deepened when the government proposed curbing public holidays of religious and historical significance. France soon ground to a halt: on September 10 and 18, major unions and civic groups staged nationwide strikes that paralyzed the country. On the 18th alone, over one million protesters flooded the streets, occupying roads, ports, airports, and railways. Schools, hospitals, and factories shut down, and in some areas, fires and violence erupted, plunging France into chaos.

Zucman Calls on “Super-Rich to Pay More Taxes”

Amid the deadlock between austerity and resistance, the “super-rich wealth tax” has emerged as an alternative. The idea was proposed by Gabriel Zucman, a professor at the Paris School of Economics and former adviser to U.S. Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. His plan would impose a 2% levy on individuals with net assets exceeding $110 million. Taxpayers would be required to contribute at least 2% of their net worth in combined income and social contributions; those falling short of that threshold would pay an additional top-up tax.

Following the resignation of Prime Minister François Bayrou, who failed to push through a spending-cut budget, Zucman declared that it was time for France’s wealthy to “open their wallets.” According to his estimates, about 1,800 French households would fall under the new tax, generating an additional $22 billion in annual revenue. The “Zucman Tax” cleared the lower house in February but was blocked by the conservative-controlled Senate. Arnault’s wealth explosion, however, has revived hopes of its eventual passage.

With France facing an urgent need to slash $48 billion from next year’s budget, Zucman’s proposal has captured overwhelming public support. Recent polls show that 86% of French citizens favor the tax — including 92% of Renaissance Party supporters and 89% of Republicans. The rare near-unanimity spans both left and right. “We must stop making the poor, workers, and retirees bear all the sacrifices of austerity,” said Fabien Villedieu, head of the SUD-Rail union. “It’s time for the wealthiest people in this country to pay their share.”

The newly formed cabinet under Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu is reportedly eager to secure left-wing cooperation, making adoption of Zucman’s proposal increasingly plausible. President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist Renaissance Party is also said to be considering endorsing the measure — a tax that affects only 0.01% of citizens and thus offers substantial political gain at minimal cost.

Critics Denounce “Self-Interest Disguised as Morality”

Just months ago, Macron and his centrist allies dismissed the wealth tax as a relic of socialist France. Former President François Hollande, a member of the Socialist Party, had introduced a similar measure in 2013 after campaigning on promises to use wealth taxation to overcome the economic crisis. His government imposed a 75% levy on annual salaries exceeding $1.1 million.

The results, however, were negligible. With only 2,000–3,000 taxpayers subject to the tax, the fiscal gains were modest. According to France’s finance ministry, the tax raised just $290 million in 2013 and $180 million in 2014 — a combined total of $470 million, less than 1% of the $76 billion collected in overall income taxes.

Unintended consequences soon followed. In 2013, celebrated French actor Gérard Depardieu renounced his French citizenship for Russian nationality to escape the tax, while Arnault, under public fire, temporarily applied for Belgian citizenship before withdrawing the request. The finance ministry estimated that losses from emigration and tax flight reached $9 billion annually, with as much as $256 billion in French capital leaving the country during that period — a phenomenon economists dubbed the “Paradox of Taxation.” The government ultimately scrapped the wealth tax in 2015, just two years after its introduction.

Opponents argue that reviving the measure would again drive the wealthy out of France. No other country has yet implemented a similar policy, and critics warn it could trigger capital flight, destabilize financial markets, and undermine job creation if business assets are included in the tax base.

Arnault himself has been outspoken in opposition. In a statement to The Sunday Times last month, he called the proposal “not an economic or technical debate, but a deliberate attempt to destroy the French economy.” He accused Zucman of “weaponizing pseudo-academic theories to advance an ideology intent on dismantling the only system that truly serves the common good — a free-market economy.”

Some experts argue that France’s tax debate transcends economics, reflecting a deeper crisis of perception. “French society speaks of communal justice,” said one economist, “but in reality, it is dominated by self-serving logic — a worldview where one’s own class interests are moralized. Self-interest is wrapped in the language of virtue, suppressing the very engine of national productivity under the guise of equality.”

Neither higher taxes nor spending cuts appear viable. France’s tax-to-GDP ratio stood at 45.6% in 2023 — the highest in the EU — while social spending accounted for 32% of GDP, well above the EU average of 26%. Analysts warn that the nation’s fiscal crisis could deepen further with upcoming credit ratings from Moody’s and S&P due this month and in November. Any downgrade would raise bond yields and exacerbate debt-service burdens, fueling a vicious cycle. Economists describe France as “too big to fail, yet too big to save” — once a pillar of eurozone stability, it is now increasingly seen as a systemic risk at the heart of Europe.

Comment