“A Market Out of Orbit, A System Stuck in Limbo” — South Korea’s Elusive Stablecoin Framework

Input

Modified

Regulatory vacuum stalls institutional adoption

Illegal trading and manipulation cloud the market

Global peers build rails for the digital dollar era

While major economies are racing to integrate stablecoins into their financial systems to strengthen trust and control, South Korea remains mired in endless debate. Recent parliamentary audits reignited discussions on regulatory frameworks, yet key issues such as issuers, supervisory structures, and reserve management remain unresolved. As speculative capital continues to distort the market, both the Bank of Korea (BOK) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) have warned of growing foreign-exchange volatility in the event of mass redemptions or reverse remittances.

Stalemate over who should issue

According to industry sources, the Financial Services Commission (FSC) plans to release a draft framework for stablecoin regulation as early as this month. The draft is expected to take center stage at the upcoming parliamentary audit on October 20, likely triggering an intense debate over requirements for issuance, supervisory authority, and qualifications for potential issuers.

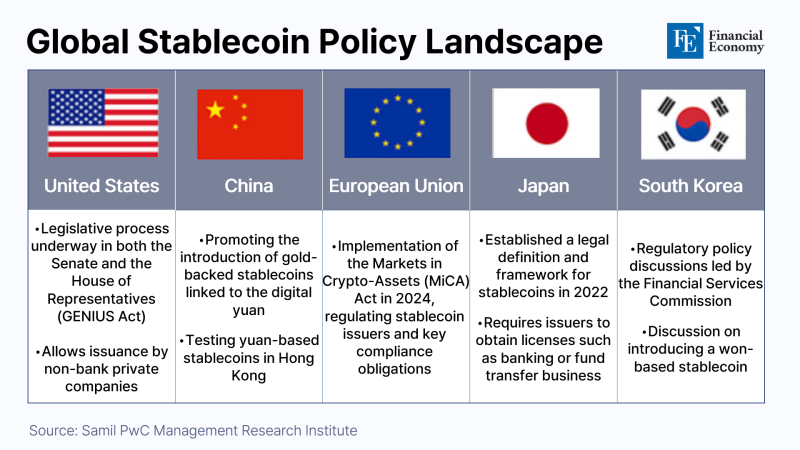

While South Korea remains stuck at the “legislative review” stage, other major economies are already expanding ecosystems under finalized frameworks. In July, President Donald Trump signed the GENIUS Act, allowing private entities to issue stablecoins on the condition that they hold reserves equal to 100 percent of the issuance in either U.S. dollars or short-term Treasury bills. Issuers must be licensed by the Federal Reserve, and all reserves fall under Fed supervision.

The European Union has similarly moved ahead with its Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation, classifying digital assets as either payment or investment instruments and differentiating capital requirements by issuance structure. Japan, through amendments to its Payment Services Act in 2023, has limited issuance to banks and trust institutions.

By contrast, at least six bills related to digital-asset regulation are still pending in South Korea’s National Assembly. Overlapping drafts—such as the Act on Value-Stabilized Digital Assets and the Basic Act on Digital Assets—have left unclear which authority should hold ultimate oversight: the FSC, the Financial Supervisory Service, or the BOK. The FSC favours allowing private innovation, while the BOK insists that monetary stability must take precedence. Unless the two sides bridge their divide, the upcoming draft may amount to little more than a political gesture.

The government continues inter-agency consultations over core issues, including full reserve backing, capital adequacy for issuers, and the potential overlap between stablecoins and central-bank digital currency (CBDC). Yet even working-level talks remain inconclusive, deepening market uncertainty. Industry experts warn that “stablecoins should be viewed as part of payment infrastructure, not just as virtual assets,” adding that “continued regulatory hesitation will cost South Korea its position in global settlement and clearing markets.”

A speculative market overshadows monetary sovereignty

Recently, abnormal price movements in dollar-denominated stablecoins such as USDT and USDC have alarmed local exchanges. On October 14, USDT traded around $1.05 on Upbit and Bithumb—well above the prevailing dollar exchange rate of $0.95—and at one point briefly spiked to nearly $4.00, signaling extreme short-term overheating. The basic “1 coin = 1 dollar” peg had collapsed. As automated repayment systems kicked in on certain lending platforms, investors were forced into liquidations.

Observers attribute this instability to the absence of market-maker systems. The surge in stablecoin prices, they argue, reflects thin retail-driven liquidity and structural inefficiency in domestic trading venues—underscoring the need for institutional market-making. Market makers quote continuous bid-ask spreads, inject liquidity, and cushion abrupt price swings. Ironically, the very need for such measures exposes the extent to which normal price-formation mechanisms have already broken down.

The Bank of Korea views this volatility through the lens of weakened monetary sovereignty. The spread of stablecoins, it warns, could undermine control over foreign-exchange flows and fuel illegal remittances or money-laundering. The industry counters that existing virtual-asset laws fail to reflect market realities: current rules prohibit exchanges from handling tokens issued by related entities, effectively severing the chain from issuance to payment and distorting real demand.

In addition, rigid enforcement of real-name account and remittance regulations at banks has widened the price gap between local and global markets. Flawed laws and inflexible oversight have thus become both the root cause and the consequence of the instability.

The BIS has also sounded alarms about systemic risk in stablecoin reserves. While short-term government securities can dampen rates under normal conditions, they amplify shocks when redemptions surge and capital outflows accelerate. In a recent report, the BIS noted that “large-scale redemptions or reverse remittances in South Korea could heighten foreign-exchange volatility,” and recommended at least minimal safeguards—full reserve backing, bank custody, designated market makers, and mandatory disclosure by issuers—to integrate stablecoins safely into the regulated system.

A risk to financial-market stability

As South Korea remains bogged down in regulatory wrangling, global peers are already constructing institutional infrastructure based on trust and interoperability. Following the GENIUS Act, the U.S. has advanced the Clarity Act, which clearly delineates supervisory powers between the SEC and the CFTC and establishes a comprehensive legal framework for issuance, trading, and custody of digital assets. The EU’s MiCA regime explicitly details issuer licensing, reserve management, and redemption procedures.

The focus of global discourse has shifted from whether to adopt stablecoins to how to design systems that balance financial stability with innovation. Market infrastructure, too, is evolving around what officials call the “rails of trust.” Regulatory models now emphasize reserves held in cash or short-term Treasuries and permanent redemption windows for consumers.

The global payments network SWIFT is testing interoperability between traditional bank rails and blockchain-based systems—linking next-day (T+1) settlement cycles in banking with real-time blockchain transactions. In this structure, dollars move through traditional bank channels while tokenized assets are processed on-chain simultaneously, ensuring that digital-asset payments complement rather than disrupt conventional finance.

Against this backdrop, South Korea’s legislative delay reflects more than a simple lack of urgency. At its core lies a deeper conflict over the boundaries of monetary control. While financial regulators champion private-sector participation under the banner of innovation, the BOK resists private issuance on grounds of monetary order. Both sides have defended their positions without defining a division of roles, leaving the industry trapped in an endless loop of pilot programs within a legal vacuum.

As institutional design continues to lag, the market risks hardening into a “no-rules zone,” where price distortions, illicit transfers, and capital reflux accumulate. Ultimately, South Korea’s challenge comes down to building a balanced model that can reconcile monetary policy with industrial policy—anchoring innovation to stability before the gap with the rest of the world becomes irreversible.

Comment