Amid Power Shortages, Future Data Centers Head for Orbit in the Race for AI Dominance

Input

Modified

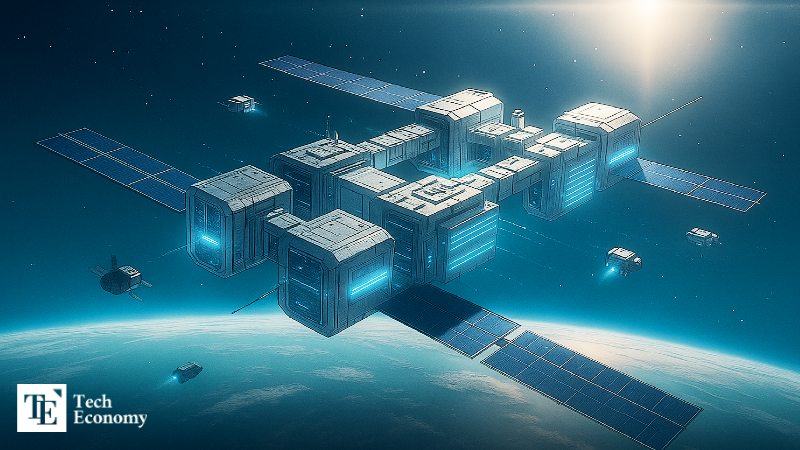

Data Center Wars Move to Space Soaring AI Computation Demands Exceed Earth’s Power and Land Capacity Solar Energy Beyond the Atmosphere Offers a Path Past Resource Constraints

The explosive expansion of artificial intelligence (AI) has driven the data center industry into uncharted territory. As computing power required for AI training and inference skyrockets, global demand for data centers has surged accordingly. Yet their massive energy consumption and heat generation have made cooling efficiency and power optimization decisive competitive factors. In this context, outer space is emerging as the next frontier. With access to uninterrupted solar energy and minimal carbon emissions—and without the need for dedicated cooling systems—space-based facilities are being hailed as the data centers of the future.

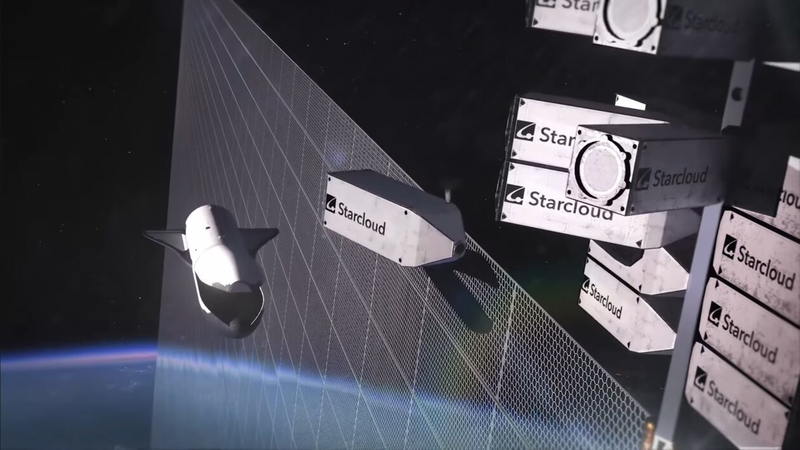

Starcloud, Google, and Lonestar Launch Orbital Projects

According to the IT and AI industries on November 11, competition to establish gigawatt-scale space data centers is heating up. The first mover is the space startup Starcloud, which earlier this month deployed its Starcloud-1 satellite equipped with NVIDIA’s high-performance H100 GPU. As the first orbital satellite to carry the H100, Starcloud-1 will provide powerful inference and fine-tuning capabilities for other satellites. Starcloud plans to follow up by launching additional satellites equipped with NVIDIA’s next-generation Blackwell platform.

Among major tech companies, Google has taken the lead. On November 4, it announced Project Suncatcher, an initiative to build data centers in orbit powered directly by solar energy. The plan involves deploying multiple small satellites, each equipped with Google’s proprietary Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) and large solar panels, into low Earth orbit. These satellites will exchange data via optical communication links, enabling large-scale AI models to operate independently of terrestrial infrastructure. Placing the satellites in a dawn-dusk sun-synchronous orbit allows them to follow Earth’s day-night boundary, maintaining near-constant exposure to sunlight. Google expects the system to achieve up to eight times the energy efficiency of ground-based solar farms.

Another contender, Lonestar Data Holdings, aims even higher—with plans to build a physical data center on the lunar surface. The company recently launched a book-sized prototype data center into orbit to validate system reliability and announced plans to construct a full-scale facility on the Moon. Its envisioned network consists of 13 satellites, each approximately 200 meters long and 80 meters wide, offering a processing capacity of 10 megawatts (MW)—comparable to a mid-sized terrestrial data center housing around 5,000 servers.

Solar Power and Radiative Cooling Slash Operating Costs

The drive toward orbital data centers stems from the urgent need to overcome the “power bottleneck” throttling AI infrastructure growth. Conventional data centers are voracious energy consumers: millions of servers run nonstop year-round, and nearly 40% of total power use goes to cooling.

Even companies like Microsoft, despite securing enough GPUs, have struggled to operate at full capacity due to local power shortages, while electricity costs have soared nationwide. Firms are experimenting with small modular reactors (SMRs) and jet-engine-based generators, but these measures have proven insufficient to offset the power demands of large-scale AI workloads.

In orbit, however, both energy and cooling constraints could be largely eliminated. The vacuum of space, averaging –270°C, provides a natural, zero-energy cooling environment—obviating the need for electric chillers or coolant loops. Meanwhile, uninterrupted solar radiation enables the generation of clean, carbon-free power around the clock. Terrestrial solar plants typically operate at only 10–24% efficiency due to weather and diurnal cycles, but orbital systems could sustain over 95% uptime. The Sun emits energy more than 100 trillion times the world’s total electricity production, offering an effectively limitless source.

Unlike ground-based facilities, orbital data centers also face no land constraints—they can simply float in orbit. Processed data would be transmitted wirelessly back to Earth, and signal latency could even be lower than fiber-optic transmission. For instance, time-sensitive financial data between New York and London could travel up to 50% faster via an orbital data relay than through undersea cables.

Crucially, current satellite design and manufacturing technologies are already advanced enough to make such facilities feasible. Existing systems for large-scale solar power generation, thermal radiation via heat pipes and radiators, and laser-based inter-satellite communication can be readily adapted. The European Union (EU) has already invested $2.1 million in a “Space Cloud for Carbon Neutrality and Data Sovereignty” initiative. A study conducted through Thales Alenia Space—a joint venture between France’s Thales and Italy’s Finmeccanica—concluded that orbital data centers can reduce carbon emissions and are technically operable.

Undersea, Polar, and Subterranean Alternatives Emerge

Beyond space, underwater data centers are also being explored as an energy-efficient alternative. The concept leverages cold seawater for passive cooling. In 2018, Microsoft deployed 864 servers in an underwater capsule near Scotland’s Orkney Islands as part of Project Natick. Over 25 months of unmanned operation, the system achieved a Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) rating of 1.07, outperforming modern land-based data centers with a PUE of around 1.12, demonstrating the superior stability of the marine environment.

While Microsoft did not commercialize the technology, China’s Highlander launched the world’s first commercial underwater data center off Hainan in 2023. The design closely mirrors Microsoft’s, using nitrogen-filled chambers and circulating seawater pipes to dissipate heat. This natural cooling method cuts power use by over 30%, eliminates the need for cooling towers, and reduces both space and water consumption. Prefabricated underwater modules can be built, deployed, and operational within 90 days, with virtually unlimited scalability.

A related approach—immersion cooling—submerges entire servers in electrically non-conductive fluid. This eliminates fans and air circulation, reducing power consumption by over 30%. The technique is especially suitable for high-density GPU clusters, positioning it as the next-generation cooling solution for AI data centers.

Cold, arid regions are another focus. Meta’s Luleå Data Center in northern Sweden, established in 2013 as its first facility outside the U.S., capitalizes on Arctic air for natural cooling. The center is powered entirely by hydroelectric energy and has operated exclusively on renewable sources since 2020.

Meanwhile, decommissioned mines are being repurposed for data storage. With stable underground temperatures and thick rock insulation, such sites offer both cooling efficiency and physical security. Norway’s Lefdal Mine Data Center exemplifies this model, utilizing 120,000 square meters of former mine tunnels and seawater cooling, while sourcing 98.5% of its power from hydroelectricity—cutting costs by roughly half compared to standard facilities. Similar projects include Bluebird Data Center in Missouri and LightEdge Data Center in Kansas, both located 20–30 meters underground where temperatures remain between 18°C and 20°C year-round—ideal for server stability and energy savings.