New Rare Earth Supply Technologies Are Emerging — U.S.–China Tensions Could Accelerate the Research

Input

Modified

Chinese researchers propose plant-based method for extracting rare earth elements U.S. seeks to strengthen its own supply chain as sourcing options expand — from coal-ash extraction to electronics recycling — amid China’s weaponization of rare earths

Chinese scientists have discovered naturally formed minerals containing rare earth elements in an edible fern. As rare earths solidify their role as essential inputs for advanced industries, new sourcing methods are emerging across the field. With the rivalry between the United States and China intensifying, analysts expect research on alternative rare-earth supplies to accelerate.

Researchers confirm monazite formation in ferns

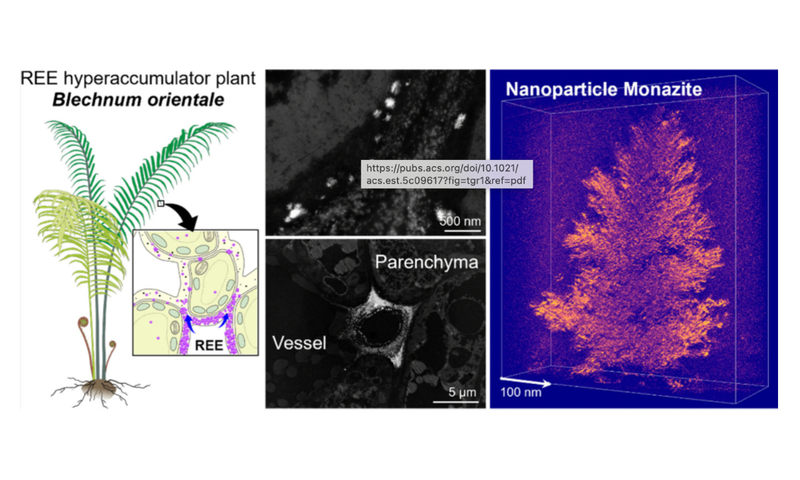

According to the South China Morning Post on the 12th, a team led by Professor Zhu Jianxi at the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, presented new evidence in the online edition of Environmental Science & Technology showing that phytomining—an eco-friendly method that uses hyperaccumulator plants to extract metals from soil—could be applied to rare earth elements. The team found that Blechnum orientale, an edible fern, contains rare earth elements at high concentrations and observed these elements crystallizing in extracellular tissues to form nanoscale monazite.

Monazite is a phosphate mineral that contains rare earth elements. In nature, it often includes radioactive uranium and thorium, making extraction and processing more difficult. But the biogenic monazite formed naturally in Blechnum orientale is considered pure and non-radioactive, suggesting a cleaner path for rare-earth recovery.

The researchers noted that cultivating hyperaccumulator plants such as ferns could both remediate contaminated soil and restore abandoned mines while recovering valuable rare earths—“a true green cycle of restoration and recovery.” He Liuqing, the paper’s lead author, added that while mineral formation is known to occur in microbes, mollusks, and corals, the mineral-forming ability of plants has long been underestimated. The discovery of rare earths in an edible fern, he said, expands scientific understanding of plant mineralization and opens a new avenue for studying more than 1,000 known hyperaccumulator species worldwide.

Diversifying pathways for rare-earth supply

A wave of new technologies for extracting and processing rare earth elements has been emerging across academia. In 2021, researchers at Cornell University published a study titled “Generation of a Gluconobacter oxydans Knockout Collection to Improve Rare-Earth Extraction,” proposing a sustainable and cost-efficient method that uses genetically engineered microbes. The team focused on Gluconobacter oxydans, a bacterium that produces organic acids capable of dissolving rock. These acids help separate phosphates from rare earth elements. By modifying the bacterium’s genes, the researchers created mutants that no longer suppress acid production. Several of these mutants accumulated rare earth elements at notably high concentrations.

In December of last year, a research team at the University of Texas at Austin reported that large volumes of rare earth elements could be extracted from toxic coal waste. Their analysis suggested that coal ash produced by power plants across the United States may contain as much as 11 million tons of rare earth elements—roughly eight times the country’s known reserves. Although the concentration of rare earths in coal ash is relatively low, the researchers noted that the U.S. generates nearly 70 million tons of coal ash annually, providing meaningful supply potential.

Technologies that recover neodymium, praseodymium, terbium, dysprosium, and other rare metals from discarded electronics are also gaining traction in the United States. Recycling companies now extract key metals not only from computers, laptops, smartphones, and servers, but also from spent electric-vehicle batteries and decommissioned wind and solar equipment. According to IBISWorld, the U.S. electronic-waste recycling industry generated $28.1 billion in revenue last year and continues to grow at an annual rate of about 8%.

Tensions between the U.S. and China may accelerate research

Analysts expect competition in rare-earth technologies to intensify. Signs of change are emerging in a supply chain long centered on China. According to the International Energy Agency, China accounts for roughly 70% of global rare-earth mining. It also controls about 90% of refining and separation capacity, and 93% of the permanent-magnet manufacturing market.

Many trace China’s dominance to years of U.S. inaction. In the mid-1990s, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States approved General Motors’ sale of Magnequench—a rare-earth magnet producer in Indiana—to Chinese buyers. Magnequench supplied magnets for computer hard-drive systems and military guidance technology. Although the buyers promised to keep the plant in Indiana, it was fully shut down a few years later. The equipment and production lines were moved to China. In 2005, the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission warned that the transaction had helped China tighten its grip on the rare-earth market, but no corrective measures followed.

The lack of support for the Mountain Pass mine is also viewed as a major misstep. The United States was the world’s top rare-earth producer through the late 20th century, led by the Mountain Pass mine in California, which opened in 1952. But stricter environmental regulations and the absence of industrial policy support forced a shutdown in 2002. When mining resumed in 2012, the U.S. processing industry had already collapsed, leaving the country reliant on China to process its own ore.

Washington is now trying to correct course. The government is making large investments in domestic rare-earth companies and strengthening partnerships with countries that have resources or processing capabilities. U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Besant said in an interview with the Financial Times last month that the United States could secure alternative supply sources within the next 12–24 months.

Still, many experts doubt the U.S. can reach self-sufficiency anytime soon. Tim Fuco, director for commodities at Eurasia Group, called Washington’s timeline “naive or overstated,” arguing that the United States lacks a realistic pathway to build an independent supply chain within one to two years. David Merriman, research director at Project Blue, which tracks the rare-earth and magnet markets, also noted that ending reliance on Chinese rare-earths within 24 months is “extremely ambitious,” requiring massive investment, permits, and workforce development.

Comment