South Korea’s Defense Industry Takes On Europe’s “Blocification,” Mounts All-Out Push for Canada Submarine Deal

Input

Modified

South Korea bets on technological edge, accelerated delivery, and whole-of-government coordination as its decisive play Germany counters with a long-horizon package tied to Norway and an industry-linked counteroffensive EU moves to harden intra-European self-sufficiency underpinned by the SAFE fund

With Canada’s Canadian Patrol Submarine Project (CPSP) estimated at up to $60 billion, South Korea’s Hanwha Ocean and Germany’s thyssenkrupp Marine Systems (TKMS) have emerged as the final contenders, elevating the competition into a litmus test for the stature and credibility of South Korea’s defense industry in the global arms market. South Korea has put forward a bid anchored in technological competitiveness, a compressed delivery timeline, and a whole-of-government industrial partnership strategy, while Germany is responding with a long-term package encompassing future development and an all-industry, fully integrated cooperation play. In particular, as Europe’s defense market sees intensifying intra-bloc consolidation, analysts say the program is likely to become not merely a contest of platforms, but a high-stakes arena of power politics and industrial order reshaping.

Canada Submarine Program: South Korea–Germany Two-Horse Race

According to military authorities and the defense industry on the 15th, the Canadian government last month confirmed South Korea and Germany as the final candidates for its submarine program and requested proposal submissions by March 2 next year. The project is a mega-program involving the acquisition of 8 to 12 submarines and is estimated at roughly $60 billion in total when long-term maintenance and operating costs are included. That is equivalent to about 10% of South Korea’s annual government budget.

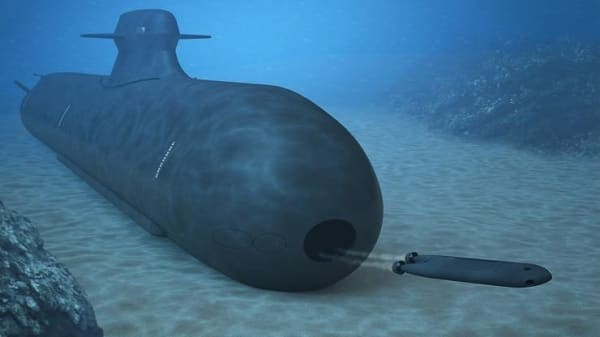

South Korea’s proposed platform is the diesel-electric KSS-III Batch-II submarine, which applies lithium-ion batteries to maximize extended submerged endurance. Given that Canada has set Arctic long-duration operational capability and emergency surfacing as mandatory requirements, the ability to sustain operations for around three weeks is expected to be a favorable factor. A faster delivery schedule is also cited as a key advantage on the South Korean side. Hanwha Ocean is said to have presented a plan under which it can deliver the lead boat within six years of contract execution. Assuming a contract is signed in 2026, the roadmap envisions delivering the first submarine in 2032 and supplying the same number by 2035, when four Victoria-class boats are to be phased out in stages. Thereafter, deliveries would proceed at a pace of one boat per year, completing the construction of 12 submarines by 2043. The proposal is assessed as focusing on minimizing the capability gap that the Royal Canadian Navy fears, while enabling a stable, long-horizon force transition.

Germany’s TKMS, the rival bidder, has offered a 40-to-50-year package—covering design, maintenance, and future development—built around a joint program with Norway. It is also advancing a government-backed, all-out cooperation strategy. The German government has already executed a cross-procurement move by spending $1 billion to adopt Canada’s CMS-330, and is expanding the perimeter of the offer by bundling cooperation on critical minerals and energy, as well as the establishment of local production facilities. Canada’s status as a NATO member and its position as Europe’s largest trading partner are also factors reinforcing that approach.

As Germany pushes an industry-wide cooperation front, the South Korean government is likewise preparing a comprehensive response that goes beyond the corporate level. At present, Seoul is working with Hanwha Ocean and other domestic defense firms to design cooperation packages across more than 10 areas—energy, space and aviation, defense industry, agriculture and livestock products, advanced technology, and infrastructure, among others—to support a CPSP win. Canada is also said to be seeking broad-based cooperation with partner countries on the back of the project. Canada has decided to 추진 economic revitalization initiatives—expanding LNG facilities, rare-earth mines and other mining assets, reactors, ports, and high-speed rail—to cushion the blow from a trade-war phase with the United States.

Poland Setback to Sweden in Submarine Contest

Industry observers say that, after South Korea fell short in Poland’s submarine program, the Canadian submarine competition could become a turning point that determines the credibility of South Korea’s defense industry in the global market. At the end of last month, Hanwha Ocean was eliminated from Poland’s Orka program for new submarines. The contest drew a full roster of major defense powers: six companies—South Korea’s Hanwha Ocean, Germany’s TKMS, Sweden’s Saab, Italy’s Fincantieri, Spain’s Navantia, and France’s Naval Group—competed, with Saab ultimately selected as the final partner.

In the wake of the Russia–Ukraine war, the Polish Navy decided to acquire three new 3,000-ton-class submarines to strengthen maritime defenses against rising military tensions in the Baltic Sea. The program is estimated at about $2.78 billion, and when sustainment and operating costs are included it approaches $5.42 billion. Saab pledged stealth and low-noise design optimized for the Baltic’s complex undersea terrain, along with technology transfer and local production with Polish defense firms. Hanwha Ocean, by contrast, was assessed as having strengths in price and delivery but lacking a robust Europe-based supply chain build-out and an industrial cooperation strategy.

Even so, the South Korean government’s strategy is to sustain bilateral defense cooperation with Poland over the long term despite the Orka setback. In this context, it is reported that Seoul proposed a free lease of a Jangbogo-class submarine to Poland. Poland currently operates only one ex-Soviet submarine, making a five-year capability gap unavoidable until new submarines are delivered. UK market research firm GlobalData analyzed that “South Korea’s proposal for free delivery would help immediately resolve Poland’s military shortfall,” adding that it could also play a meaningful role in “restructuring crew training systems and transitioning technical standards.”

Geographic Similarities Tilt Advantage Toward Europe

However, some argue that large European defense projects carry structural constraints behind the scenes. Poland’s Orka program—where South Korea came up short—is being driven by the SAFE (Security Action for Europe) fund jointly created by 19 EU member states. In particular, Poland has been allocated $176.16 billion, the largest amount among the 19 countries. To use SAFE funding, a condition applies requiring at least 65% of total components to be sourced within the bloc, creating political and institutional burdens for procurement from non-European suppliers.

The issue is that this architecture is not confined to the Polish case. Similar signals are being detected in Romania’s $3.39 billion armored vehicle program. In that project, Hanwha Aerospace’s Redback is competing against Germany’s Rheinmetall KF41 Lynx. Last month, Bloomberg reported that Romanian military authorities had signed a contract not with South Korea’s Redback but with Germany’s KF41 Lynx. A week later, the Romanian government denied it, but the episode has been interpreted as showing that Eastern European states pushing rearmament cannot ignore Germany’s weight inside the EU.

This environment could also work against South Korea in the Canadian submarine program. On the 1st (local time), Canada decided to join the SAFE fund as the first non-European country, as part of a strategy to reduce reliance on the United States and diversify security partnerships. Canada plans to use tools such as low-interest loans and subsidies to pursue submarine and fighter procurement. Going forward, Canada may also be subject to preferential terms for European-made weapons, and cooperation with European defense contractors could expand production within Canada. Such factors increase the likelihood that Canada’s SAFE participation could tilt in Germany’s TKMS’s favor.

Beyond political considerations, geographic conditions are also cited as reinforcing Europe-centered cooperation patterns. Germany, which is competing against South Korea, shares the Arctic Ocean with Canada as a core operational theater—echoing the way Sweden, sharing Baltic Sea geography, secured a favorable position in Poland’s submarine program. In other words, geographic and strategic common ground is increasingly acting as a key variable in procurement decisions. In last year’s Australian frigate program, South Korean firms were also said to have been eliminated in part because they failed to fully meet Australia’s operating environment and requirement set.

Comment