Europe Loses 9% of Chemical Capacity as Investment Freezes, Shockwaves Reach Auto Sector

Input

Modified

Rising Costs and Weak Demand Drive Closure Wave

Industrial Spillover Intensifies, Manufacturing Ecosystem Shaken

EU Deploys Tariffs and Security Measures Against Chinese Competition

A new study has found that since 2022, a wave of factory shutdowns across Europe’s chemical industry has wiped out large-scale production capacity while triggering simultaneous job losses. New investment, meanwhile, has fallen sharply and failed to keep pace with the decline in facilities. The contraction in basic chemicals has spread into the automotive and components sectors, prompting the European Union (EU) to pursue trade and security countermeasures, including tariffs and the exclusion of foreign equipment. As weakening industrial foundations intersect with supply chain realignment, Europe’s broader manufacturing sector is facing a critical test of its strategic direction.

Major Companies Cut Output and Shut Plants

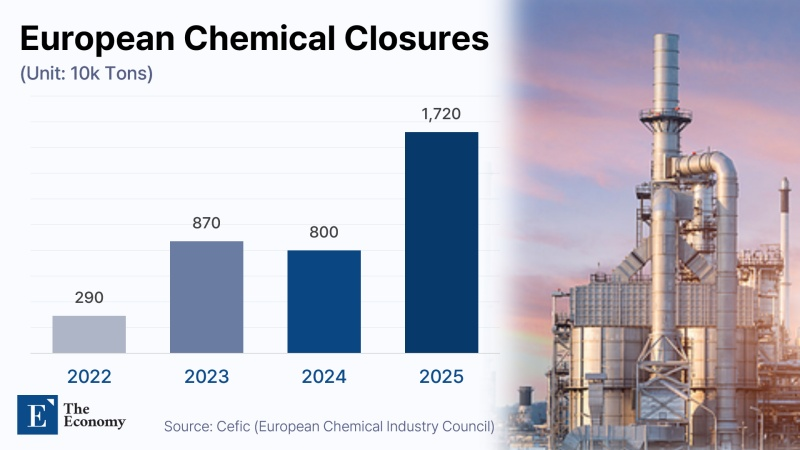

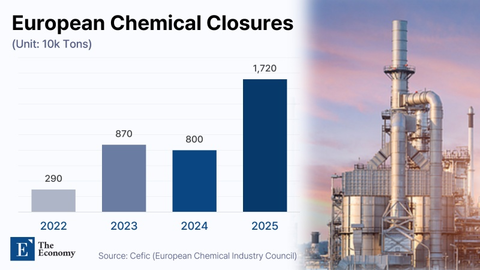

According to the European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC) on the 19th (local time), Europe’s chemical sector lost a cumulative 37 million metric tons of production capacity between 2022 and last year. That represents roughly 9% of total European chemical production capacity, with about 20,000 direct jobs eliminated in the process. Management consultancy Roland Berger, which conducted the study on behalf of CEFIC, warned that “when supply chain ripple effects are taken into account, an additional 89,000 indirect jobs are at risk,” adding that “new investment is not keeping pace at all with the speed at which existing production facilities are being lost.” The expected annual capacity of newly built facilities dropped from about 2.7 million metric tons in 2022 to roughly 300,000 metric tons last year.

A significant share of the closures has been concentrated in petrochemicals. About 48% of total shuttered capacity occurred in that segment, with half of it stemming from the shutdown of nine steam crackers. By country, Germany accounted for 25% of the closures, followed by the Netherlands at 20%. Marco Mensink, Director General of CEFIC, emphasized urgency, stating that “this is not the time to debate whether we are five minutes before or after the point of no return,” and called for immediate decisions that could have tangible on-the-ground effects this year as both closures and investment declines accelerate.

Company-level cases underscore the severity of the crisis. ExxonMobil decided to permanently shut its ethylene plant in Scotland this month. The facility, which began commercial operations in 1985 and operated for more than four decades, had an annual capacity of 830,000 metric tons and was regarded as one of the United Kingdom’s flagship ethylene production sites. LyondellBasell also moved to sell two ethylene crackers—one in Berre, France (465,000 metric tons annually) and another in Münchsmünster, Germany (400,000 metric tons)—along with a polypropylene plant in Tarragona, Spain (390,000 metric tons annually). The fact that all were slated for permanent closure or divestment rather than temporary suspension highlights the gravity of the situation.

The decision by INEOS Inovyn, a core chemicals subsidiary of the INEOS Group producing vinyl, PVC, and chlorine-based feedstocks, has also become emblematic. In October last year, the company shut two plants in Rheinberg, Germany, resulting in at least 175 job losses. CEO Stephen Dossel used stark language, warning that “Europe is committing industrial suicide,” and lamented that while competitors in the United States and China benefit from cheaper energy, European producers are falling behind in price competition due to domestic policies and the absence of tariff protection. Prior to Rheinberg, Inovyn had already closed facilities in Grangemouth in the United Kingdom and Zwijndrecht in Belgium, while suspending operations in Tavaux, France, and Martorell, Spain.

Raw Material Contraction Spreads to Autos and Components

The crisis in chemicals is increasingly spilling over into related sectors such as automobiles and parts. Germany’s largest automaker, Volkswagen, decided to close a domestic plant for the first time in its 88-year history. The Dresden facility, which began operations in 2002, is a representative example. Although it produced fewer than 200,000 vehicles in total—making it relatively small—it served as a technological showcase for flagship models such as the luxury sedan Phaeton and the electric vehicle ID.3, amplifying the symbolic impact of its closure. In addition to Dresden, the Osnabrück plant is also set to halt operations, which is expected to reduce Volkswagen’s annual production capacity in Germany by about 734,000 vehicles.

The intensity of restructuring is also unprecedented. In an agreement reached last year, Volkswagen management and labor representatives agreed to eliminate more than 35,000 jobs in Germany, equivalent to roughly 30% of its 120,000 domestic workforce. The company had initially proposed closing at least three of its ten German plants and cutting wages by 10%, but the final agreement included a plan to allocate a 5% wage increase into a corporate fund to support cost reductions. Chief Financial Officer Arno Antlitz said the company faces ongoing tariff burdens of up to $5.9 billion annually and intends to review its five-year investment plan totaling $188.8 billion.

The components sector has not been spared. France-based tire manufacturer Michelin plans to close two domestic plants in the first half of this year and cut 1,250 jobs, representing about 7% of its French workforce. Earlier, in early 2024, Germany’s second-largest automotive supplier ZF announced the closure of two plants and warned that up to 12,000 layoffs could be unavoidable over the next six years, while another supplier, Schaeffler, unveiled plans to cut roughly 4,700 jobs around the same time. The German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA) estimated that more than 46,000 jobs have disappeared in Germany’s automotive supplier sector over the past five years since 2019 and projected that cumulative losses could reach as high as 190,000 by 2035.

Industry participants broadly agree that this cascading restructuring cannot be viewed separately from the contraction in chemicals. Basic chemical products such as ethylene, polypropylene, and synthetic rubber are widely used in tires, plastic components, and lightweight vehicle materials. As a result, reduced feedstock production inevitably feeds directly into cost structures for both automakers and suppliers. Combined with aggressive expansion by Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers and declining parts demand associated with the transition to EVs, Europe’s manufacturing ecosystem is facing simultaneous pressure on employment and capital investment. The shrinking production base that began in chemicals is spreading into autos and components, amplifying the broader industrial impact.

Rising Risk of Trade Conflict with China

These developments have intensified calls for EU-level countermeasures. The European Commission is reviewing options to maintain or finalize countervailing tariffs of up to 45% on Chinese electric vehicles. In particular, companies deemed uncooperative with investigations, including SAIC, could face the maximum tariff rate of 45.3%. The move reflects concerns that Chinese vehicles—whose price competitiveness is bolstered by subsidies—cannot be allowed to undermine local industrial foundations that are already under strain. Analysts also suggest the EU aims to block potential surges of redirected exports into Europe resulting from U.S. tariff policies.

Exclusion measures against Chinese equipment have also strengthened in telecommunications and digital infrastructure. On the 21st of last month, the South China Morning Post reported that the European Commission plans to legislate requirements forcing member states to remove Huawei and ZTE equipment from 5G networks. Since 2020, the EU had recommended excluding such equipment over cybersecurity risks, but the absence of binding enforcement limited effectiveness. If the legislation is adopted, forced removal would have to be completed within three years. Huawei argued the move would violate principles of fairness and proportionality, but the EU has instead signaled potential expansion of exclusion measures into other advanced sectors, including connected vehicles and cloud computing.

China, meanwhile, has emphasized the need for dialogue. Earlier this month, Wang Yi, Director of the Office of the Central Commission for Foreign Affairs of the Communist Party of China, told Emmanuel Bonne, France’s diplomatic advisor, in a phone call that “China and Europe are partners, not competitors,” adding that “both sides have the ability to coordinate and resolve specific trade disputes through dialogue.” The remarks are widely interpreted as reflecting concerns that if Europe also raises tariff barriers while access to the U.S. market remains constrained, China’s export-driven strategy could face significant disruption. If policy efforts to offset weak domestic demand through export expansion lose momentum, China’s medium- to long-term growth trajectory could also require adjustment. That intersection—between EU tariff and regulatory responses and China’s calls for dialogue—has become a focal point of international attention.

Comment