When Rules Fail and Data Deliver: Rethinking Trust in Granular Clinical AI

Input

Modified

Granular clinical AI fails when institutions reward simplicity over conditional accuracy Data fragmentation and weak governance turn powerful tools into brittle automation Trust will emerge only when policy aligns incentives with subgroup-tested performance

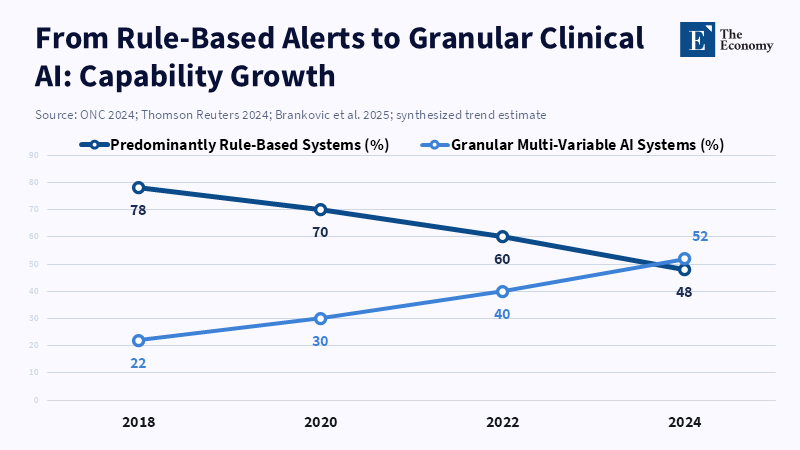

In 2024, a substantial 71% of hospitals in the U.S. reported using predictive analytics in their electronic health record systems. It's like a fast-moving tech wave, but there's something important hiding under the surface: what kind of is actually being used. Many of these systems are simple, automated tools built on basic rules. They send alerts and flags. We should focus on developing a more detailed clinical. This means creating systems that use connected patient information, employ condition-based decision-making procedures, and employ a logic that has been tested on different patient groups. In this way, the system can select from different treatment options specific to the patient. This is important because a detailed model can recommend a specifically designed action, rather than merely issuing a simple warning. What we mean by “detailed clinical ” is that we are making a design choice; it's not merely something we hope for.

Detailed Clinical vs. Keeping Things Simple: What's the Real Difference?

The first issue was misinterpreting the term. Instead of being a technical term, it turned into a brand name. As a result, the market began rewarding the cheapest products labeled with the label. For example, a sepsis alert that triggers when a lab result exceeds a certain threshold is easy to check, easy to explain, and quick to implement. However, a detailed model examines changes in vital signs over time, medication history, other illnesses the patient has, and the treatment setting. Those models are more difficult to develop, require richer data, and require ongoing maintenance. However, they provide specific recommendations for elderly patients who are frail, patients with kidney problems, or people with weakened immune systems. These specific suggestions help prevent situations in which a doctor faces a simple decision with only two options and must choose between expensive actions when they are unsure of the right choice. The main question we need to decide is not whether to use it, but what type to approve, purchase, and pay for.

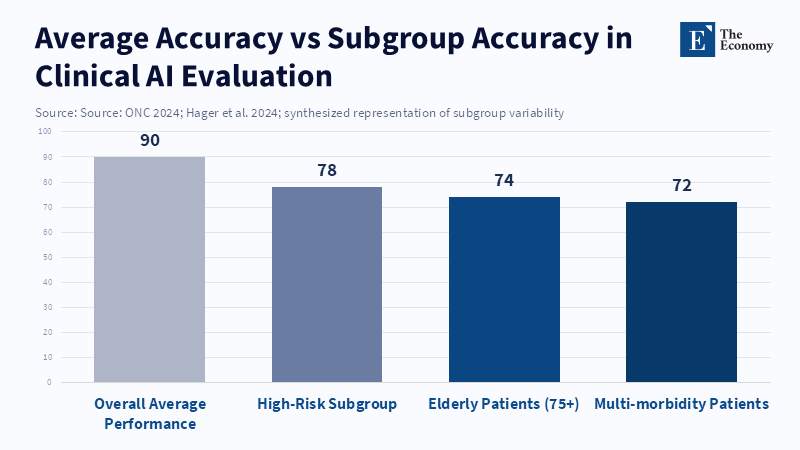

The desire to choose simple automation is reinforced by both buyers of these systems and those responsible for setting the rules. Approval processes that focus on aggregate metrics, such as overall sensitivity, specificity, or a single AUC value, make it appealing to improve the average. A company can enter the market with strong overall numbers but may be missing common scenarios in specific groups. This isn't just a concept; it happens in the real world. The averages obscure failures in smaller groups. If the review process is not thorough, buyers of these tools will see products that appear valid in presentations but are disappointing when used with real patients. This leads doctors to lose trust and become resistant to later, better systems. If we want healthcare to be safer, we have to ensure the evaluation covers every part of the process. We should also use these systems in real-world settings. By doing this, companies will get paid for being reliable in specific situations, not just for having good averages.

A common way the story about patient safety ends is when a doctor trusts and something goes wrong. However, the story ends there, which is incomplete. A study published in JAMA notes that one limitation was the consideration of only the effect on registered imaging orders, which means the tool may have often presented users with simple choices between two options because it did not account for broader clinical outcomes or include more advanced decision-making rules. The doctor's choice then becomes the last step in a series of engineering decisions. If we review safety in this way, we can shift the focus to earlier in the process. We can begin asking questions such as: Was the model trained on realistic data? Did it have the factors needed to identify the different situations? Was it tested in the background before it was used? If we ask and answer these questions before use, the unfortunate event may never happen because the system wouldn't force a doctor to make a bad choice.

How Data, Design, and Skills Affect Whether It Is Detailed or Simple

The details start with the data. In many medical systems, patient information is distributed across multiple sources, including hospital records, outpatient records, specialty department records, imaging platforms, and the devices they use. Measurements taken at home, rehab notes, and information from remote monitoring may not be consolidated into a single record that can be easily searched. When data is separated like that, engineers can't assemble the full picture of the patient needed to choose among different courses of action. When the information is missing or not consistent, teams will usually use easier methods using simple thresholds and broad groups that can still work despite the confusion. These shortcuts can reduce failure rates during initial use in complex situations. But they can create unreliable systems that fail without warning when something changes. So, data that can be used with other systems and shared labels are needed for detailed systems. Without them, we'll keep building simple, fragile automation.

Design is very important. Rule-based models are clear, verifiable, and effective when there are only a few clear rules. They're still useful tools. But rule lists don't scale well as the number of clinical situations grows, and they can have interactions. Maintenance costs increase significantly, and there are many unusual cases that need to be accounted for. Machine learning frameworks can learn how different factors interact and support different decision options, but only if they are trained on diverse, well-labelled, and accurate datasets. So, when we move from using rules to detailed models, it's not because we want complicated black boxes. It's because we want better data, more transparent documentation, easy-to-understand interfaces, and evaluation methods that test how components work at each step in the system.

The final piece of the puzzle is the workforce's ability. A model that looks good won't be much help if a healthcare system lacks the experts to maintain the pipelines, data scientists to design tests for different groups, and physicians trained to run tests in the background before using the system. According to a recent study published by JMIR, when hospital staff are not actively involved in the design of clinical decision support systems, hospitals tend to opt for simpler tools that are easier and quicker to implement, even if more advanced options could offer greater safety in the long term. Public funding for shared platforms for labelling, training programs for data-related roles in clinics, and regional audit centers would enable smaller hospitals to use detailed tools without having to perform the heavy technical tasks themselves.

What Officials Can Do: From Rules to Workforce and Evaluation

Policy can change motivation at a high level. Purchasing rules should require evidence for each step of the process. They should also require companies to report how the system performs across medically relevant scenarios and across different decision paths. Before a product is widely used, buyers should require background testing in realistic clinical settings. Approval organizations should look beyond simple metrics and use tests that stress the system to identify where simplified rules fail. These actions would create an economic incentive for companies to invest in more complex engineering that supports accuracy across different scenarios. Purchasing is simple, and it can be very that way. If purchasers ask for evidence for specific situations, companies will work to meet that requirement.

Rules and payments can also push the market toward more detailed systems. Those who approve the systems could require clear documentation of the training data, the data sources, and the system's limitations. According to ASTP, in 2024, many hospitals relied on predictive AI from various sources, and using incentives, including payment or purchase priority, could encourage the adoption of reliable products that are consistently monitored after implementation. However, these approaches may increase development costs and extend the time required for products to reach the market. Those are real trade-offs. But the option is an industry that produces many modest victories and some high-cost failures that cause reputation harm, legal risk, and real harm to patients. Paying more for reliability is an investment in solid confidence and long-term use.

There is clear evidence supporting a careful approach. Tests of new clinical models show that good average performance does not guarantee consistent performance across all situations. Large-scale tests of language and decision models in clinical settings have found that they can fail to follow directions and are influenced by the order and phrasing of input. This challenges the claim that they are ready to make decisions independently. From various procedure-focused studies, we have learned that it can change how doctors act and reduce their performance when they lack the tool. This underscores the importance of habit and reliance in maintaining skills over the long term. These outcomes indicate that we need to conduct background testing and monitoring and employ careful strategies to minimize unintended skill loss.

Misinformation and corrupted data are another danger that can be measured. Recent experiments show that models are more likely to accept and spread false clinical information when it is included in realistic, official-looking clinical notes than when it appears in informal social media content. That weakness is important because poorly vetted data can appear trustworthy to an algorithm. Defenses are both technical and organized. We need to verify the data source, validate the input, assess the confidence level, collect continuous feedback from doctors, and commit to post-use verification to close the loop and reduce risk. These steps shift the balance from unreliable automation toward reliable help that doctors can trust.

The risk we face now is not a general worry. It's the market choice to reward simple rules and call them intelligence. Detailed clinical systems designed to guide patients through many tested, conditional, and clear paths are the better option. Getting there requires three coordinated actions from policymakers, purchasers, and funders: require evidence for each step and for different groups in procurement; invest in data that can integrate with other systems and shared labeling infrastructure; and fund workforce roles and monitoring capacity to run and monitor conditional models safely. These are not small requests. They are the systems, oversight, and labor required to ensure automation is safe. If policymakers, purchasers, and funders make those choices, doctors will find a class of tools they can trust. The option is more unreliable systems, more safety events, and a slow loss of trust from doctors. The choice should be clear to those who care for patients.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Autor, D., Dorn, D. and Hanson, G. (2015) ‘Untangling trade and technology: Evidence from local labour markets’, Economic Journal, 125(584), pp. 621–646.

Burning Glass Institute (2024) The Emerging Degree Reset: How the Shift to Skills-Based Hiring Holds the Keys to Growing the U.S. Workforce at a Time of Talent Shortage. Boston: Burning Glass Institute.

Employer Branding News (2025) ‘The vanishing first rung: How AI is dismantling the graduate job market’, Employer Branding News.

Forbes (2026) ‘As AI erases entry-level jobs, colleges must rethink their purpose’, Forbes, 30 January.

Indeed Hiring Lab (2024) Labour Market Trends Report 2018–2024. Austin: Indeed.

International Monetary Fund (2024) Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work. Washington, DC: IMF.

McKinsey Global Institute (2023) Generative AI and the Future of Work in America. New York: McKinsey & Company.

Petrova, B., Sabelhaus, J. and others (2024) ‘Robotization and occupational mobility’, Brookings Institution Report, Center on Regulation and Markets.

Rest of World (2025) ‘Engineering graduates and AI job losses’, Rest of World.

World Economic Forum (2023) The Future of Jobs Report 2023. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Comment