State-Backed IPOs and EU Capital Markets Reform: Why Europe Needs Enforced Mission Finance

Input

Modified

State-backed IPOs are emerging as a strategic tool, not just a market event Europe’s capital reform will fail without credible public risk-sharing and enforcement Democratic accountability and mission finance must be designed together, not treated as trade-offs

The discussion around capital markets in Europe often goes in circles. There's plenty of money available, but few companies are going public. So, public markets haven't really grown, even though other countries are changing their rules to support key industries. People get worried or excited about government-backed IPOs, but the truth is that how money is used has always been influenced by governments. The main difference is whether the government sets clear goals or just offers suggestions. Right now, Europe has a lot of private money (venture capital stood at €53 billion at the end of 2023), but it's hard to secure public funding for important companies, and such funding often comes with many strings attached. We need to stop acting like the problem is just about sharing information or fixing the markets. It's about how things are run: who takes the risks, who makes sure things get done, and what compromises are acceptable when innovation is a big priority for the country.

State-backed IPOs and why Europe’s reform talk misses the point

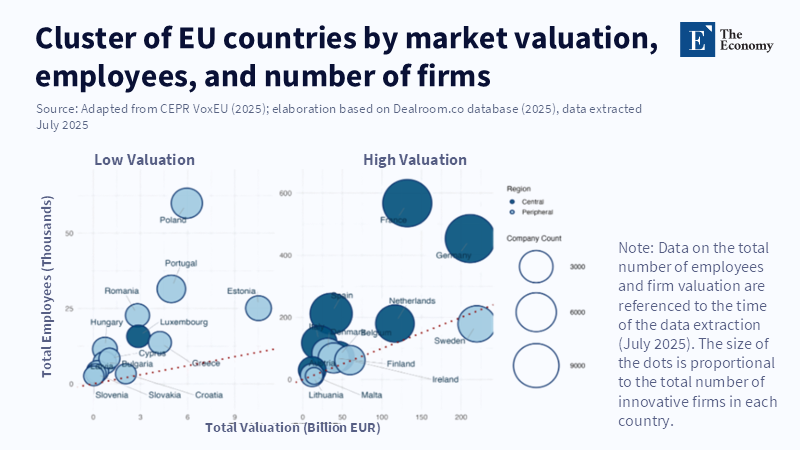

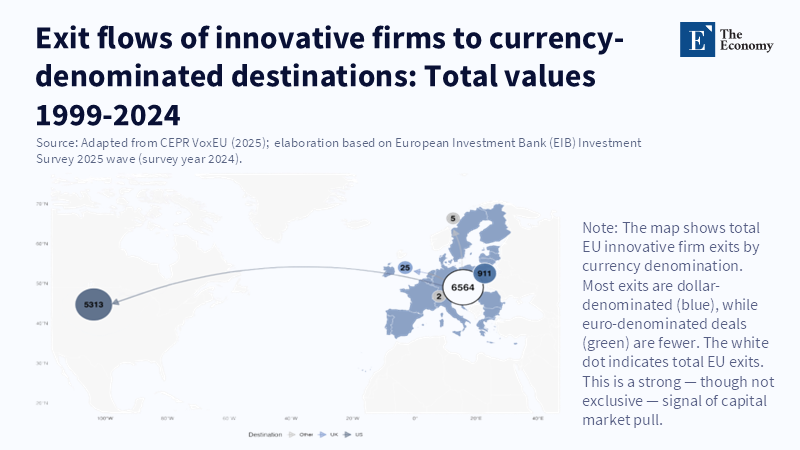

Europe’s usual reform script treats capital-market weakness as a liquidity and regulatory problem. The prescriptions repeat: harmonise rules, ease listing costs, improve disclosure, nudge retail investors. Those are useful. But they do not confront the deeper question that the phrase state-backed IPOs forces on us: if public policy treats listings as instruments of industrial strategy, who underwrites the long tail of risk and how are governance incentives reshaped? The EU proposals we hear often assume persuasion and incentives will suffice. That belief presumes private markets will take the leap once the rules are tidied. Evidence from recent years argues otherwise. European private capital is sizable and patient in aggregate, yet IPO markets for transformational firms remain episodic. Continental IPO proceeds rebounded in 2024 but remained dominated by a small number of large floats and private-equity exits—not an organic pipeline of mission-driven, tech-deep businesses that the bloc claims to need.

This matters now because geopolitical competition has hardened. State actors are no longer passive spectators in capital allocation. In 2025, Beijing adopted rules that allow certain advanced manufacturing and space firms to qualify for fast-track listing paths—effectively lowering traditional profitability thresholds if firms meet defined technological milestones. That is not mere market tinkering; it is a deliberate redefinition of what a public offering can mean in the service of policy. Reuters and market reports indicate that China is relaxing IPO rules for reusable-rocket firms and enabling large state and quasi-state funds to underwrite growth. In short, capital policy is now a tool of industrial policy in other major jurisdictions. Europe must choose whether to be a reactive observer or to design its own accountable version of mission finance.

How the Numbers Are Used

When I talk about the total amount of money (such as venture capital), I'm using industry figures that show the totals at the end of a period. When I mention IPO numbers, I'm using reports that add up all the deal values. These numbers are rounded to make things easier to understand. The exact amounts aren't the main point. What matters is the overall picture: there's money available, but important companies aren't going public consistently, and changes that ignore how things are enforced probably won't make a big difference.

This is important now because countries are competing more fiercely. Governments aren't just watching from the sidelines when it comes to how money is used. In 2025, China enacted regulations that allow certain advanced manufacturing and space companies to go public more quickly. According to a recent article from Intereconomics, policymakers are intentionally changing the standards for public offerings by relaxing profit requirements for companies that meet specific technological objectives, signaling a strategic shift in what an IPO represents for industrial policy. News reports show that China is making it easier for reusable rocket companies to go public and allowing big government funds to support their growth. Basically, how money is used is now a tool of industrial policy in other major countries. Europe needs to decide whether it will merely react to these changes or develop its own system for funding key industries responsibly.

What China's Government-Backed IPO Approach Really Achieves — and What Europe Doesn't Understand

The Beijing Stock Exchange and its specific listing rules are instructive because they reveal the choices and compromises involved, rather than a single perfect model to copy. China's system clearly prioritizes industrial policy goals over extensive trade. They're amenable to low trading in some areas if important companies receive funding and policies are coordinated. This is a deliberate choice. Analysts have noted that the Beijing model prioritizes policy over trading activity and uses stock exchanges to fund small and medium-sized companies in key industries.

Two things make this model work in China. First, the government is willing to share the risk of losses by providing direct funding, using government-owned funds, or offering better underwriting options. Second, there's coordination among regulators, industry groups, and government finance groups to ensure that companies that qualify for listing meet strategic goals. The result isn't better markets in the traditional sense, but it's a way to fund important industries that encourages long-term growth. News reports about companies like LandSpace show how it works: the government relaxes profit requirements, and government funds invest in the companies before they go public.

Europe tends to misunderstand these things. Politicians often see government support as just making the market easier, which means small changes and tax breaks rather than actually sharing the risk. The problem is political: many European countries and the EU as a whole don't want to provide large-scale public funding to private companies because it appears to be industrial policy or government aid. Democratic countries want responsibility and fair competition. But without reliable government support, even when Europe develops helpful ways to list companies or ESG guidelines, the private sector still has the final say. This isn't just a neutral issue; it affects which companies receive funding and which national priorities go unmet.

Look at the numbers on venture capital and IPOs. The venture capital scene in Europe was still doing okay in 2025, but not as well as in previous years. The amount of money flowing in each quarter showed that investors were avoiding risk. Reports from KPMG and InvestEurope indicate that private capital is available, but there are insufficient public options for important strategic investments. This explains why merely reforming the public markets, without mechanisms to share risk and enforce strategic commitments, will likely yield the same old reform seminars and similar recommendations.

How to Design Government-Backed IPOs Responsibly in Europe

If the problem is how things are run rather than just making the rules the same, then the solution needs to change incentives and create clear ways for the government to share risk that fit with democratic values. Here are three principles to guide Europe's next steps in reforming government-backed IPOs:

- Create public co-investment funds with conditions for important companies that have strict performance goals. This doesn't have to mean the government owns the companies or provides permanent subsidies. Instead, government co-investment should be tied to specific goals, like patents, emissions reductions, production numbers, or supply-chain connections, with penalties if they aren't met. Europe already has funds and ways to blend public and private financing. They should be changed to focus on co-investment that has clear timelines and is driven by results. This increases the government's influence while maintaining political oversight. The system must be clear to avoid hidden government aid and make sure that procurement and competition rules are followed.

- Create a clear fast-track listing category for companies that meet specific public-interest criteria, along with a government underwriter of last resort that accepts some losses in exchange for governance safeguards. The Chinese example works because underwriting is coordinated, not random. Europe should do the same coordination without the secrecy. A government backing facility could operate under a parliamentary mandate, publish its terms, and require private co-investors to participate to avoid moral hazard. This protects democratic scrutiny while making listings credible for important companies.

- Invest in governance capacity after listing: This includes government representation in shareholder agreements, independent monitoring, and sunset clauses. Listings backed by government funding shouldn't turn into permanent government control. They should have pre-agreed exit plans and reporting that measures not only financial metrics but also strategic outcomes.

Critics will argue that these steps introduce inefficiencies into industrial policy or politicize markets. The best response is to provide evidence and be transparent. Government support without clear criteria can lead to favoritism, a significant risk that must be guarded against. But the alternative—doing nothing beyond small technical fixes—means that strategic companies will either move to countries with better funding options or remain underfunded. Recent market trends indicate that private capital is becoming more concentrated, private equity is playing a larger role in exits, and IPOs in Europe aren't generating substantial capital. Small regulatory changes will not address these patterns. Market summaries indicate that recent activity included strong private equity involvement in IPOs, highlighting how private capital often drives when and how companies list, rather than public mission needs.

The suggestions above combine legal and financial tools. Specific numbers for facility sizes and underwriter exposure should be based on member-state mandates and EU budgetary rules. The main thing is the structure, not a specific euro amount.

The fact that there's plenty of private capital but few public listings of major companies indicates a governance problem. Government-backed IPOs aren't a perfect solution, but they're a deliberate policy tool used by other countries. Europe can either accept being a rule-maker that markets ignore, or it can create responsible, democratically supervised systems that share risk, enforce outcomes, and maintain market discipline. The message is simple: stop treating capital-market reform as a theoretical exercise. Build transparent co-investment facilities, create clear fast-track listing categories with government underwriting under strict agreements, and require oversight and exit plans after listing. If Europe wants to be independent in technology and reduce emissions, it needs to match its diagnoses with enforceable tools, not just another report that restates the problem. The test for democracy is whether we can fund ambition without sacrificing responsibility. It's time to show we can.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Angadi, S. (2025) ‘Rule-Based AI Systems: The Foundation of Intelligent Automation’. Medium.

Brankovic, A. et al. (2025) ‘Clinician-informed XAI evaluation checklist with metrics (CLIX-M) for AI-powered clinical decision support systems’. npj Digital Medicine.

Hager, P. et al. (2024) ‘Evaluation and mitigation of the limitations of large language models in clinical decision-making’. Nature Medicine.

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) (2024) Hospital trends in the use, evaluation, and governance of predictive AI, 2023–2024. Data Brief.

Reuters (2024) ‘Transforming healthcare with data and technology’. Thomson Reuters Special Report.

Reuters (2026) ‘Medical misinformation more likely to fool AI if source appears legitimate, study finds’. Thomson Reuters.

Scientific American (2024) ‘AI Is Entering Health Care—and Nurses Are Being Asked to Trust It’. Scientific American.

Thomson Reuters (2024) ‘Data fragmentation and its impact on institutional systems’. Thomson Reuters Technology Insights.

Comment