Marking the Real: Why authenticity markers — not bans or panic — must save education from the deepfake fallacy

Input

Modified

Deepfakes are spreading faster than fact-checking systems can respond, eroding public trust Treating all AI-generated content as fake is a policy mistake that weakens education Authenticity markers offer a practical way to rebuild trust without banning useful AI tools

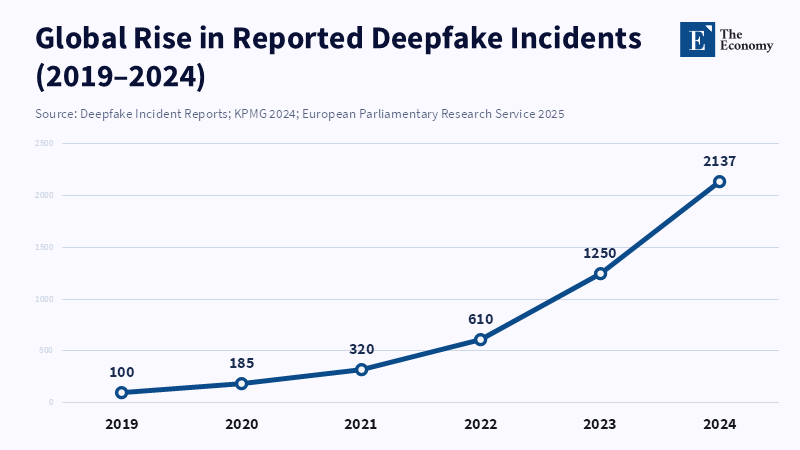

Analysis by parliamentary bodies indicates that in 2024, a deepfake incident surfaced at an alarming rate of roughly every five minutes. The speed at which these incidents occur is important because a fabricated voice or image can spread and become part of the cultural environment before it can be properly identified and addressed. It's tempting to view anything generated by Artificial Intelligence with automatic skepticism. However, such an approach would be a tactical mistake. The problem isn't that computer programs can produce convincing content. The true risk emerges when we allow the label 'AI-generated' to become synonymous with 'fake,' discarding methods to verify authenticity. A viable solution is to embed strong yet user-friendly authenticity markers into the tools and practices commonly used by students and teachers. These markers come in different forms: technical (watermarks, cryptographic verification), professional (creator credentials), and educational (methods to understand media origins). If educational institutions start with the assumption that AI equals fraud, they risk promoting mistrust rather than critical thinking, which leaves society vulnerable to those who spread misinformation quickly.

Why the idea that AI-generated equals fake is bad for policy, and why authenticity markers offer a better solution:

Initial reactions to generative AI typically go through three stages: amazement, moral outrage, and calls for regulation. This often results in labeling AI-created content as suspicious and demanding outright bans or restrictive measures. While this reaction is understandable, it is unsustainable in the long run and distracts focus from constructive approaches. Many schools and organizations have begun using generative tools to draft documents, gather responses, and increase accessibility. Banning or discrediting AI output would harm legitimate educational uses, such as language practice, brainstorming, and getting feedback, while allowing malicious actors to spread convincing forgeries.

In contrast, authenticity markers allow teachers to distinguish the origin of content from its persuasiveness. According to the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence, requiring students to provide a transparency ledger—detailing which parts were AI-assisted, the prompts used, links to all sources, and a brief explanation of their verification process—can help teachers focus on evaluating the authenticity of the work rather than restricting specific tools. The goal is not blind trust, but verifiable trust based on data and procedures.

Systems for verifying origin are not theoretical concepts. Standards such as Content Credentials and the C2PA specification outline how to embed tamper-proof data into images, videos, and audio files. This way, viewers can check the file’s history and origin. Institutions that adopt these standards enable students to confirm the authenticity of their work without banning useful AI functions. The emphasis moves from policing the tools used to documenting the work’s development. This change preserves educational progress while making it more difficult for malicious individuals to falsely claim authorship without leaving traceable records.

Creating Trust: Technical, Social, and Classroom-Ready Authenticity Markers

To create a system that’s useful for education, we need three types of markers that complement each other: (1) technical markers embedded in the content, (2) identity-linked credentials for creators, and (3) classroom norms that encourage clear documentation of origin.

Technical markers include hidden watermarks, content credentials, and cryptographic records. Research on watermarking has made progress, offering reliable methods for watermarking text, audio, and images that can withstand common changes and be detected with standard tools. According to a report from the Australian Cyber Security Centre, Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, and the UK National Cyber Security Centre, applying Content Credentials during the creation of media in places like a school media lab or through common authoring applications attaches cryptographically signed metadata to the content, helping verify its origin and making it more difficult for others to pass off the material as entirely new.

Identity-linked credentials link creators to a verified identity using methods such as institutional email verification, simple identity confirmation, or campus-managed keys that sign a content record. These credentials don’t require intrusive biometric systems. They only need to be strong enough to discourage casual impersonation and easy enough for students to use. When combined with content credentials, a signed record can show that “Student A” created the file at a specific time, with a specific editing history, including details about the use of AI tools. This enables instructors and classmates to evaluate not only the final product, but also the process used to create it.

Social markers consist of classroom guidelines and clear indicators. Teachers might require a brief statement of origin with each submission (Created by X; used tools Y; edits Z; content credential attached), and learning management systems could display an icon or link to view the C2PA record. These design choices are important because people tend to trust interfaces. If a student sees an authenticity badge that leads to a readable chain of custody, they will be less likely to assume fraud and more likely to think carefully about the content. International groups and standards-setting organizations are already working to create technical standards for these markers via workshops and meetings on watermarking and multimedia authenticity. Using these standards gives schools a practical way to put markers to use without creating new cryptographic methods or metadata formats.

From Theory to Practice: Important Data and Design Notes for Policy Makers

Policy talks often get bogged down in numbers. Here are some specific, verifiable points that can be used in real-life applications.

First, the frequency of deepfake incidents and misuse is increasing quickly, according to independent analysis and reports from various institutions. One major review of incident reporting found large year-over-year increases in the number of detected deepfake attacks. Identification rates in certain sectors increased by several hundred percent in 2023–24. This increase explains why educators feel pressured to take action. However, the proper response is to reduce risk through markers and documentation of origin, rather than implementing outright bans. Requiring content credentials offers greater value at lower cost than sweeping bans, as it reduces the harm from a forged file without preventing students from using generative tools for learning.

Second, implementing origin documentation is achievable, as recent industry implementations have shown that it is practical to include origin information at scale. Major content platforms and infrastructure providers have added content-credential inspection and preservation options that cover a large portion of the web. According to Viet Vo and colleagues, OblivCDN can download large video files very quickly, completing a 256 MB download in just 5.6 seconds. Faculty members can verify the chain with a single click, and graders can focus on the quality of the argument rather than policing tool use. This adoption at the infrastructure level changes origin documentation from a desired state to an operational state.

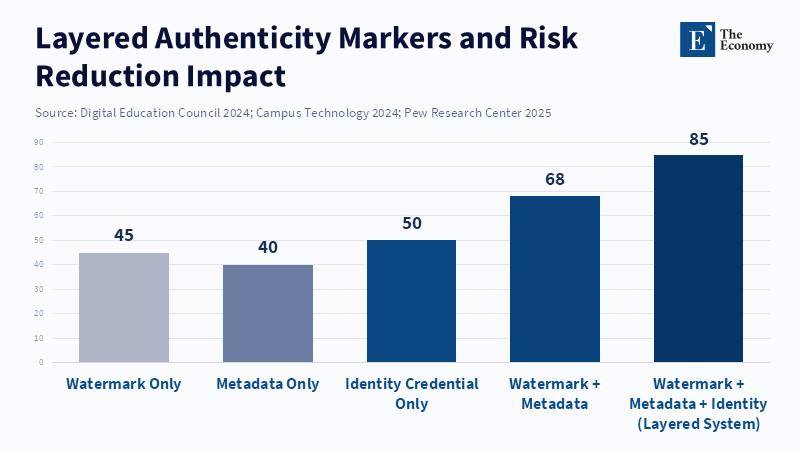

Third, there are technical limitations to consider. Watermarking and credential systems are not perfect. Hidden markers can be attacked, and metadata can be removed, which is why cryptographically signed records and server-side preservation are necessary. When complete certainty is not possible, transparent estimates should be used. For example, when estimating the percentage of posted images that keep their credentials after being reposted, use retention rates from pilot studies (e.g., 50–70 percent in controlled hosting environments) and adjust policy to require both embedded marks and server-side storage of records. Combine layered defenses (watermark, record, and identity) and measure retention and identification rates in actual deployments, rather than relying on a single solution.

Immediate, Practical Steps for Educators, Administrators, and Policy Makers:

Adopt requirement-by-design: Require origin metadata on any media assignment that will be graded. Keep the requirement simple: a visible line of origin information plus an attached content credential. Provide templates and LMS support to make this easy for students. This reduces enforcement costs and makes documentation a normal part of media creation.

Fund verification basics: Equip campus servers or institutional repositories to preserve signed records on upload. Do not rely only on third parties. When institutions keep main copies, they maintain control. This step is inexpensive compared to the damage to reputation and legal costs of a widespread forgery involving campus content.

Teach origin literacy: Add short modules that explain what a content credential shows and how to interpret a record. This is not advanced cryptography but rather simple civic tech: reading a chain of custody, telling apart signed edits from anonymous reposts, and understanding what a watermark can and cannot prove. These skills are essential for media literacy in the age of AI.

Anticipated Criticisms:

Markers are sometimes seen as surveillance or as a burden on creativity. While it is important to prevent surveillance, this can be addressed through policy design. Require only minimal identity confirmations (institutional email verification, not biometric keys), store records under clear retention policies, and give students control over which works are made public. Creativity prospers under clear origin rules because authors can confidently claim and protect their work. It's true that markers can be forged or removed, but layered defenses (embedded, signed, and server-preserved) raise the cost of forgery enough to make casual misuse and opportunistic fraud far less appealing. There's also the concern that markers may strengthen the role of large tech companies as gatekeepers. To address this, open standards (C2PA, Content Credentials) and interoperable inspection tools must be institutionalized rather than outsourced to a single business. International standards and multi-stakeholder governance make markers a public good rather than a proprietary gate.

Going back to the initial point, the rise in deepfakes is a warning, not a reason to stop all digital progress. Education needs to turn this alarm into a permanent, humane verification system. Authenticity markers offer a different path: instead of banning tools or treating AI as inherently fraudulent, insist that important media carry a readable trail. This trail serves a civic purpose, allowing students to show their work process, instructors to assess the process and the product, and institutions to preserve evidence when problems occur. Systems like Content Credentials, cryptographic records, and resilient watermarking are ready for practical use. The governance and training needed to ensure their success require combined efforts from government officials and teachers. Policymakers should require public funds for original infrastructure in schools and mandate standards that allow creators to remain in control. Administrators should make origin documentation a standard part of submission processes and preserve the main copies. Educators should teach original literacy alongside critical reading and source evaluation. By executing these actions, the term AI-generated will shift from a negative label to a neutral statement, accompanied by documentation of the work’s creation. In an age of instant fakes, this documentation remains education’s strongest defense.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Adobe Content Authenticity Initiative (2025) Content Authenticity Initiative: Restoring trust and transparency in the age of AI. Adobe.

Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) (2024) C2PA Specification Version 2.3. C2PA.

Dufour, M. (2024) ‘Deepfakes are getting faster than fact-checks, says digital forensics expert’, Scientific American.

KPMG (2024) Deepfake: How real is it?. KPMG International.

Lyu, S. (2024) ‘Deepfakes are getting faster than fact-checks’, Scientific American.

World (2024) ‘From doubt to trust: How proof of human helps combat deepfakes’, World.org.

Future Media Hubs (2024) ‘Building trust in a deepfake world: The importance of ethical AI practices’, Future Media Hubs.

WellSaid Labs (2024) ‘The dangers of deepfakes’, WellSaid Labs Blog.

Comment