The Missing Treaty: How a US–China Breakthrough on AI Could Stop AI Misuse Proliferation

Input

Modified

AI misuse is spreading faster as advanced models become widely available National safeguards alone cannot contain cross-border diffusion of high-risk systems A targeted US–China agreement is crucial to slow global AI misuse

According to research by Sarah Gao and Andrew Kean Gao, since late 2022, there has been a rapid surge in large language model development, with hundreds of new models announced each week and nearly 16,000 text generation models uploaded to public repositories like Hugging Face. This rapid growth could create challenges for effective oversight and regulation. All models, regardless of size, increase the risk of misuse. Currently, the growth and availability of these technologies are occurring simultaneously. Systems with great abilities are becoming less expensive to operate, simpler to copy, and easier to change. The core issue is the widespread availability of these tools. Refined systems are leaving research labs and rapidly spreading to markets, online communities, and the toolsets of those with malicious intent. This spread is fueling the increase in AI misuse, radically changing how we can prevent it. Relying on law enforcement alone is not enough to keep up. To address this problem, the two leading AI nations need to agree on a framework that limits the spread of AI misuse while still enabling legitimate research and education. If these two countries do not come to an understanding, the problem will grow faster than regulations can manage. This will leave educators and officials constantly reacting to problems they were not prepared for.

Why AI Misuse Requires a US–China Strategy

Addressing the spread of AI misuse requires a joint strategy between the United States and China because, while it is natural for decision-makers to see AI misuse as a local issue and try to fix it by tightening export controls, funding national defense, and updating laws, these actions alone are not sufficient. The ways in which AI capabilities can cause actual harm, such as model information being leaked online, open-source versions being easily shared, and foreign cloud services offering inexpensive computing power, all operate internationally. Most recent primary models were developed by industry, meaning private companies in different countries control how they are distributed. Actions taken at home can only slow, but not stop, the spread of models when they are created in one country and copied in another. This is where a two-way approach becomes important. If the United States is the only country restricting the export of specific chips or software, other countries might not. This would leave their systems open, and misuse would spread through cloud services, copies, open licenses, and international companies. Because of this, policies need to include strong domestic elements and an international agreement that can be implemented by the two main countries involved.

Schools, colleges, and training programs will always need local safety measures. But these measures only work if the global environment does not offer easy ways to get around them. According to CNBC News, U.S. officials are working to close loopholes in policies that prevent AI chip exports to China, but these efforts are focused on hardware restrictions and do not aim to stop research itself. Teachers and school network officials should still prepare within a world where powerful code can be easily accessed online through public platforms or simple web searches, and any agreement between the United States and China does not attempt to halt research. It should instead focus on the important points of spread, such as the intentional export of leading models, the uncontrolled sharing of model information, and the sale of ready-to-use systems that make improper use more likely. Enforceable limits at these important points would greatly improve the effectiveness of local policies, allowing educators time and space to create protections that are educationally valuable rather than just quick reactions.

Evidence Behind the Surge in AI Misuse Proliferation

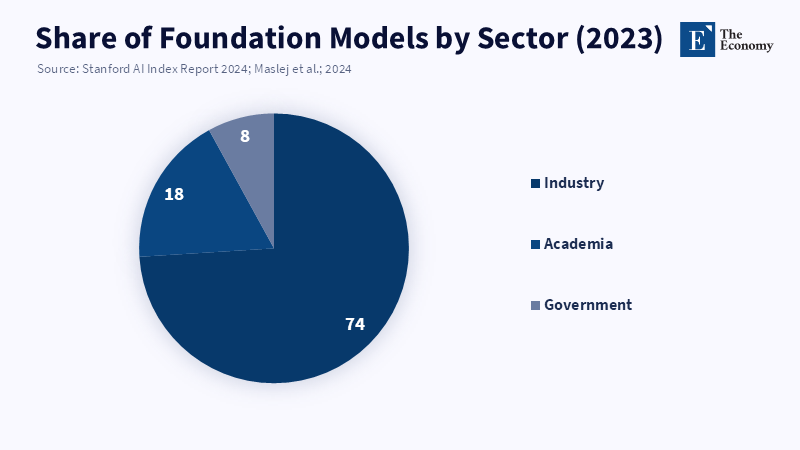

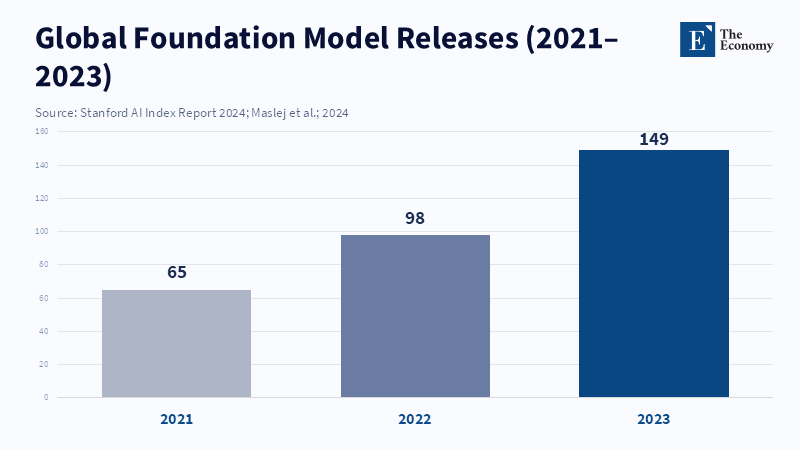

The data is clear: there has been a spike in model releases and copies, and the industry is responsible for most of this growth. In 2023, the number of new large language models released worldwide nearly doubled compared to the year before, with the industry producing about three-quarters of these primary models. It is important to understand that these numbers indicate that more codebases, datasets, and deployment tools are available for someone with little experience to change and use. The rise in releases means tools for abuse are becoming available more quickly. These tools can be used to automate phishing efforts, create malware, or produce large-scale, convincing false information. The figures cited come from industry surveys and reports. The term "doubling" and the percentages used refer to year-over-year increases in public model releases and primary model announcements, compiled by a neutral source.

Several cases show how an ordinary leak can result in extensive access. Early in 2023, the data from a top research model was quickly copied and shared after it was released to only a limited group. Within a few days, others had altered the model, making it usable on standard computers. This leak made it simple for people without expertise to adjust and repackage the model for tasks that are difficult to control using laws alone. This case shows how openness, licensing gaps, and weak international law enforcement can combine to increase risk. The lesson for educators and policy teams is not to give up, but to understand the issue's structure. When strong capabilities are inexpensive and ways to spread them are varied, the best plans are those that affect supply chains and legal rules at the beginning, rather than just trying to block misuse at the end.

Policy Levers to Slow AI Misuse Proliferation

There are four feasible actions that could be effective: export controls on important hardware, consistent licensing rules for model releases, certification by a trusted party for business uses, and shared mechanisms for responding to misuse. These tools already exist in different forms. Export controls can slow the shipment of the most advanced chips, licensing can limit open sharing, certification can require companies to put safety checks in place, and incident responses can coordinate removals. The problem is having consistency and incentives. Each action creates winners and losers. Strict hardware controls benefit countries that produce their own components, restrictive licensing slows open science, and certification creates exclusive gatekeepers. Without a trustworthy two-way agreement, both sides will use these actions to their own advantage, which explains the current standstill.

The political situation is simple. According to a report from AP News, China’s Commerce Ministry criticized U.S. export controls on advanced computer chips, stating that such restrictions harm global supply chains and result in significant losses, and warned that China will take steps to protect its own interests. This creates a situation where both sides could benefit from working together; reduced proliferation of misuse is a global public good. However, each side worries about being at a disadvantage. The way forward is practical: start by concentrating on specific, verifiable actions that reduce the most dangerous ways misuse spreads, while still allowing beneficial innovation to compete. For example, jointly define the limits on computing power and model size that would require export or licensing actions, create shared standards requiring model distributors to register uses above those limits with a neutral registrar, and establish similar legal systems to quickly remove illegal items across borders. These actions are not a perfect solution. They require trust and ways to check compliance. Both governments must understand that not working together will cost more than agreeing to some clear limits.

A Practical Roadmap to Contain AI Misuse Proliferation

Here is a practical plan for educators, administrators, and officials to reduce the spread of AI misuse. First, educators need to recognize misuse as a learning risk that can be anticipated. This means designing courses that teach safe practices, such as secure model handling, reduced data use, and threat analysis, and including responsible-use clauses for research projects and the tools they produce. Administrators should set minimum standards, such as using approved computing vendors, maintaining model inventories, and imposing clear penalties for misuse. These actions reduce the risk of leaks on campus and lower the chance that student projects will be used for actual harm. However, these local actions only provide some time. They are most effective when combined with a policy approach which addresses supply.

Second, policymakers should negotiate a specific agreement. It should begin with a small scope, focusing on three key control points: (1) the export of top-tier chips and pre-built systems that exceed a verified computing threshold, (2) mandatory registration of business model distributions that go beyond a certain capability, and (3) mutual legal agreements for the swift removal of illegal model collections and data. The agreement should include methods for technical verification, such as cross-certified measurement of computing operations, neutral registrars for high-capability uses, and agreed-upon audit standards. It is important that the agreement includes exceptions for academic research under strict controls, as well as review clauses to protect beneficial innovation. These steps are compatible with competition. They are specific, verifiable, and focus directly on how misuse spreads rather than on scientific exchange. They also significantly improve the effectiveness of local educational safeguards by removing the global loopholes that allow misuse to spread.

In closing, the fact that public model releases doubled in a single year is more than merely a statistic. It is a warning that capability and distribution are now linked. If unattended, this connection will turn any innovation into a potential source of misuse. The policy goal is not to stop progress, but to control the channels through which advanced systems move. A specific, enforceable agreement between the United States and China, focused on the control points of spread, is the most practical way to improve the effect of local safeguards and training practices. Educators should strengthen their classrooms and curricula, administrators should secure their institutional supply chains, and policymakers need to pursue a realistic, verifiable agreement. If the two leading AI ecosystems fail to act together, misuse will continue to grow faster than ways to prevent it. If they do act, we gain the ability to teach, learn, and innovate without always having to fix the problems caused by uncontrolled distribution.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Allen, G.C. (2023) China Is Beating the US in AI Supremacy. Cambridge, MA: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School.

Blumenthal, R. (2023) Letter to Mark Zuckerberg regarding LLaMA model leak. U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology, and the Law, 6 June.

Ding, J. (2018) Deciphering China’s AI Dream: The Context, Components, Capabilities, and Consequences of China’s Strategy to Lead the World in AI. Oxford: Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford.

Goldstein, J., Pifer, S., and Rasser, M. (2024) Reading Between the Lines of the Dueling US and Chinese AI Action Plans. Washington, DC: Atlantic Council.

Maslej, N., Fattorini, L., Brynjolfsson, E., Etchemendy, J., Ligett, K., Lyons, T., Manyika, J., Ngo, H., and Niebles, J.C. (2024) The AI Index 2024 Annual Report. Stanford, CA: Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence.

Sheehan, M. (2022) China’s AI Regulations and How They Get Made. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Villalobos, P., Heim, L., Besiroglu, T., Hobbhahn, M. and Sevilla, J. (2022) ‘Will We Run Out of Data? Limits of LLM Scaling Based on Human-Generated Data’, arXiv preprint.

Weber, S. and Chahal, H. (2024) ‘AI Risks from Non-State Actors’, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Comment