When Money Misses the Mark: Why “Early-Birth” Subsidies Fail Without Structural Change

Input

Modified

Cash bonuses cannot fix delayed childbearing policy failures Later births reflect structural insecurity, not lost desire for children Only institutional reform can shift fertility timing sustainably

The most telling number is simple: across wealthy nations, the mean age at first birth rose by roughly three years between 2000 and 2022 — from about 26.4 to 29.5. That single shift rewrites the policy playbook. It states that the childbearing bubble shifted, not vanished: couples are not having fewer children because cash cheques are absent; they are having children later because life now requires later stability—stable housing, stable work, stable hours, and predictable childcare. The policy answer that many governments keep offering — one-off payments, birth bonuses, and lump-sum home grants intended at persuading people to have babies earlier — treats timing as a demand problem that can be solved with discrete payments. It cannot. This piece reframes the debate: the issue is not only fertility levels but the social conditions that push fertile years into mid-life. If policy aims to shift the calendar of family formation, it must change the stubbornly unchanged economic calendar.

Delayed childbearing policy: reframing the question

The dominant assumption in many pronatalist programs is that money buys time. Governments imagine they can persuade twenty-somethings to start families earlier by making early parenthood cheaper. This presumes the timing choice is mainly financial and short-run. But cohort evidence and age-of-first-birth trends say otherwise: people who postpone childbearing do so because the prerequisites of childrearing — secure jobs, career trajectories that tolerate parental leave, affordable housing, and childcare — now consolidate later in life. Treating the symptom (low births among young adults) with a one-off cure (cash today) ignores the deeper sequencing problem: the life-stage ladder has shifted. If the ladder’s rungs are further apart, a cash handout will only help those already near the next rung; it will not rewire entire careers or housing markets.

This reconsideration matters now because demographic momentum is short-circuited by biology and economics. Delaying first births into the 30s reduces lifetime fertility potential for many, even when couples eventually decide to have children. The policy implication follows directly: to alter the timing of births, you must alter the timing of stability. That demands sustained, structural changes to labor markets, housing supply, and care systems — not episodic subsidies. This is not simply a technocratic claim. It changes which ministries must be involved, which budgets must be sustained, and how success is measured. Success should be measured not by births in the next quarter, but by changes in the average age at which households reach stable employment, affordable housing, and reliable childcare.

Delayed childbearing policy: what the evidence shows (2023–2025)

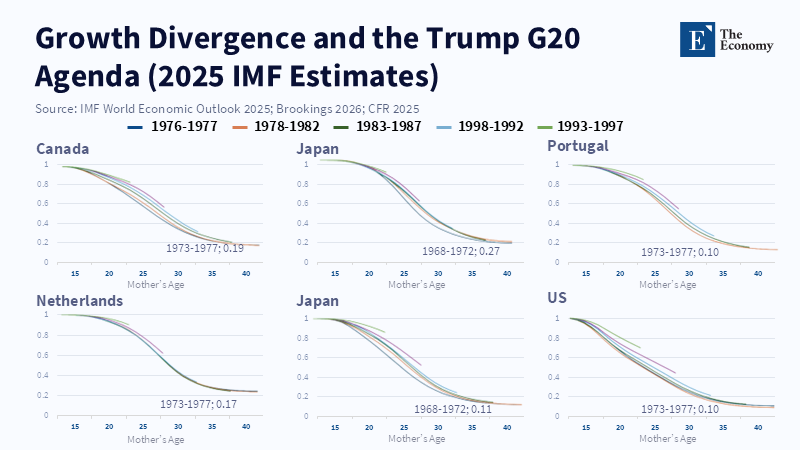

Recent international data make the mechanism visible. Across rich countries, the total fertility rate has been trending well below replacement for decades, while the mean age at first birth has steadily climbed. The interlocking outcome is simple: fewer births at younger ages and more births shifted into the thirties. These patterns are consistent across cross-country datasets and cohort studies that disentangle tempo (timing) from quantum (total number of children ever born). In short, much of the “decline” in period fertility stems from timing changes, but these can become permanent declines when delayed parenthood bumps up against biological and economic ceilings. This distinction is vital: if delayed timing is the main driver, policies that merely provide transient cash may lift short-term birth counts but will not reverse a cohort's lifetime fertility loss.

Concrete policy experiments confirm the limits of short-run subsidies. In-depth studies of broad cash payments show modest, short-lived increases in births — often concentrated among disadvantaged groups — but little evidence that a set of lump-sum or time-limited transfers returns cohort fertility to pre-existing levels. When governments pour resources into early-baby bonuses or housing grants for young couples without at the same time addressing job precarity, career penalties for parenthood, and the scarcity of affordable, quality childcare, the demographic effects are small and sometimes perverse: the subsidies create winners who bear children earlier but leave many others still constrained and worse off in the medium run because costs are reallocated rather than structural change happening. The evidence recommends realism: cash matters, but it is not a substitute for durable institutional reform.

Delayed childbearing policy: consequences for education, institutions, and decision-makers

For educators and educational institutions, the timing shift carries a quiet but powerful set of constraints and opportunities. Students who delay family formation are more likely to begin parenting while established in mid-career. That implies adult learning, workplace flexibility, and parental support services must be re-engineered to serve a different demographic profile: not teenagers or very young adults, but professionals in their thirties juggling peak career demands. Institutions should design degree pathways and certification updates that accommodate interrupted career trajectories and parental leave without penalizing progression. If educational pathways remain rigid, delayed childbearing will lead to stalled lifelong learning and, eventually, skill mismatches in the economy.

Administrators in universities, local governments, and school systems must anticipate demographic sequencing that alters demand curves. Schools will see shifts in enrollment timing and parental needs; early-childhood education demand may compress into specific cohorts; and the profile of student-parents will change. Policymakers have to therefore emphasize policies that shift the supply of stability: zoning reforms to expand housing near jobs and childcare, incentive structures to make part-time and flexible work viable without career penalties, and public investment in childcare that lowers recurring costs rather than one-off subsidies. These are not glamorous short-term wins; they are long-term commitments to the life-stage architecture that forms reproductive decisions. The critical misstep to avoid is designing programs measured by births within a single electoral cycle rather than by the steady accrual of stability spanning a generation.

Anticipating critiques and counter-evidence

A common counter-argument says: “But cash can nudge behavior — look at countries that raised payments and saw birth spikes.” Indeed, targeted cash transfers can increase births shortly after disbursement and reduce child poverty. Yet the data reveal the pattern: cash nudges boost short-term period fertility but do not dependably change cohort fertility or reverse delayed childbearing at scale. Where short-term increases happened, they often concentrated among households already on the margin; structural drivers—housing markets, insecure employment, and unequal family leave policies—remained. The sensible takeaway is twofold: use cash transfers to protect children and reduce hardship, and deploy longer-term policies to change life-course timing.

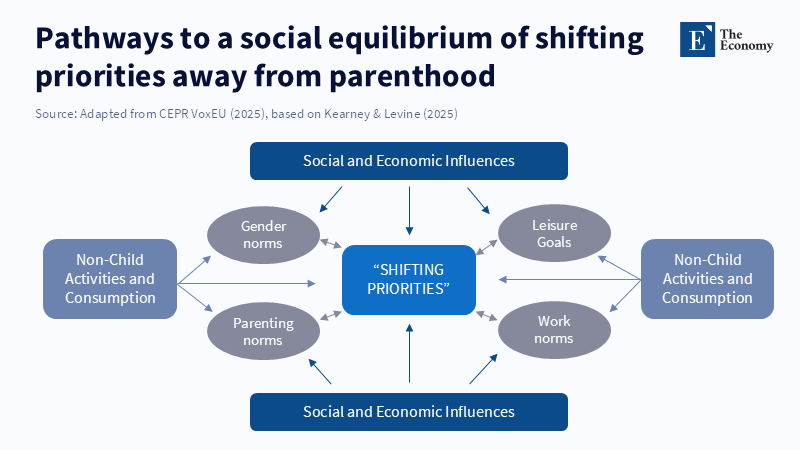

Another critique argues that cultural change, rather than economics, drives later parenthood, as younger generations prioritize careers and lifestyle choices over parenthood. Material conditions affect cultural matters, but cultures do, too. When secure employment, affordable housing, and fair parental rights are absent, culture adapts by normalizing later family formation. Moreover, the cohort evidence shows that when constraints ease—for example, through stable career tracks and affordable care—some groups advance childbearing earlier. This suggests culture and economics interact; ignoring the economic scaffolding is a policy error. Finally, even if some people freely choose delayed parenthood for lifestyle reasons, policies designed to reduce time-based penalties of parenthood can still protect the choices of those who wish to have children earlier but cannot afford to.

If the core fact is that first births are occurring later by about three years across wealthy countries, then the correct policy question is not how to sell babies to twenty-somethings. It is: how do we bring the prerequisites of families — decent, secure jobs; housing that does not devour wages; reliable, affordable care; and work that tolerates parenthood — forward in people’s life courses so that family formation need not wait? Short-term payments can and should be used where they reduce hardship. But to move the demographic needle on timing, we must redesign institutions: labor law that protects early-career parents, housing policy that expands supply near employment centers, and public care systems that lower the recurring cost of child-rearing. These are multi-decade projects measured in stability, not headlines. If policymakers accept that reality, then the next generation will decide on children for reasons that reflect preference rather than constraint. That is the only durable way to change the calendar of family life.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Cowan, S. K. (2022). Examining the Effects of a Universal Cash Transfer on Fertility. Social Forces.

Kaiser, B. (2025). Lessons from Hungary’s Failed Family Policy. MSU Institute for Law & Research Blog.

OECD. (2024). Society at a Glance 2024: Fertility trends across the OECD and the role for policy. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Reuters. (2024). Birth rates halve in richer countries as costs weigh: OECD report. Reuters.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2025). World Fertility Report 2024.

World media reports and national statistical releases (e.g., China National Bureau of Statistics) were consulted for the most recent birth counts and short-term trends.