Japan's Marketing Win Won't Stop the Debt: Why "Japan fiscal productivity" Must Come First

Input

Modified

Japan’s political win does not solve its structural fiscal problem Without stronger Japan fiscal productivity, deficits will widen as debt costs rise Only productivity-led growth can stabilize public finances without harsh tax hikes

Japan's recent election victory hinges on a big promise: tax breaks, subsidies, and incentives to work longer. Voters liked the sound of this. But there's something more important than campaign promises: Japan's financial situation. The country's debt is more than 200% of its GDP, and it's likely to remain that way unless Japan finds a way to grow faster and produce more. This isn't just talk. It's a real problem involving interest costs, an aging population, and low production. If the government only focuses on keeping taxes low and getting people to work more hours, any short-term praise won't stop the squeeze on public finances in the long run. What Japan needs is a simple change in focus: make its manufacturing and financial management the main focus. Boost production first, then growth will follow. Only then can tax breaks last without causing market problems that would make the financial situation much worse.

Viewing the victory differently: selling an idea versus staying afloat in Japan's manufacturing and financial management

Think of the recent election win as a successful sales pitch. It gave people confidence with simple ideas: lower taxes, more money in their pockets, and encouragement to work more. This sounds good because people feel stuck and haven't seen their wages increase much. But sales pitches don't change the numbers. Japan's overall financial state and long-term debt show a big difference between what's been promised and what's actually possible. The Finance Ministry's forecasts suggest it'll need to issue more bonds and manage rising debt costs over the next few years. The bond markets have already given warnings through pricing and instability. They're expressing concerns that cutting taxes without a stronger income base will lead to larger deficits. Markets consider future risks and the ability to pay debts. Politicians can get good headlines, but they can't turn those headlines into a healthy financial situation without a reliable plan to improve production, which would increase the country's potential and its ability to collect taxes.

The way we talk about this needs to change. We need to stop thinking of tax rates as the main way to provide quick relief while ignoring the foundation that generates income. The order of things is important. Production increases what each person can produce in an hour. Higher production leads to higher incomes and business profits, which expand the tax base. With a larger base, reasonable tax rates can raise revenue without hurting demand. If the government cuts taxes first but production stays low, deficits will increase. According to AP News, Prime Minister Kishida is considering an income tax cut for households affected by inflation and tax breaks for companies to encourage investment, which suggests that, alongside lower taxes, the government is looking at other economic measures rather than only resorting to harsh tax increases, spending cuts, or money printing in the future.

Why markets are uneasy: the fiscal arithmetic behind the ‘Japan fiscal productivity’ imperative

Financial markets aren't about judging right and wrong; they're about calculations. Since the Bank of Japan ended its radical measures to stimulate the economy, and interest rates have gone up, investors are less willing to take on unlimited financial risks. Higher interest rates increase the costs of managing debt, which leads to more borrowing. This creates a cycle that can quickly overwhelm budgets in a country with high debt. Recent reports show that debt-related costs are expected to increase through 2029 under the current path, due to both higher rates and debts coming due. When debt costs take up a larger part of spending, there's less flexibility for social services, defense, or investment. In other words, if growth doesn't speed up, lower tax rates won't create any breathing room. They'll make the situation worse by cutting available funds while interest costs rise.

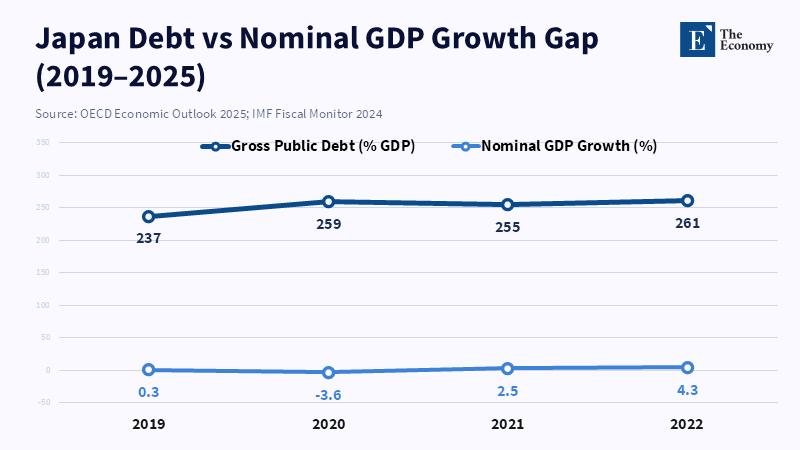

The numbers make this clear. International organizations and government agencies report that Japan's public debt exceeds 200% of GDP. Even after improvements from stimulus spending, there are still deficits in both financial and basic measures. Forecasts from reliable organizations show only slight improvements in the near future, and only if the economy grows faster than interest costs. When interest rises faster than the economy grows, debt problems get worse. This isn't just theory. The government now expects a noticeable increase in annual bond issuance due to rising monetary pressures. Independent experts state that higher interest rates are the market's way of pricing that risk. The message for policy is clear: without growth fueled by production, tax cuts financed by debt increase financial fragility, not reduce it.

The Production Gap and Realistic Steps for Japan's Production and Fiscal management

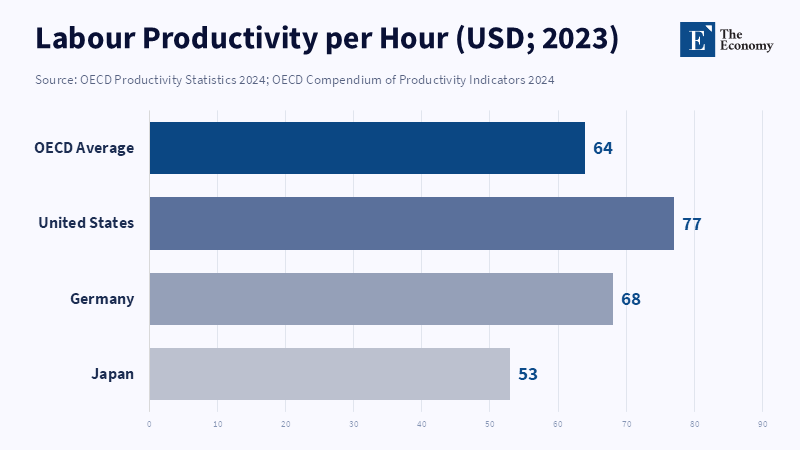

Japan's performance in production has been weak compared to other countries in recent years. Growth in labor production has been slow, and output per hour is lower than in several developed economies, even when adjusted for hours and exchange rates. Factors that weaken production include not investing enough in new technologies, rigid company management, slow adoption of digital practices in small businesses, and limited increases in production in the service sector. Closing this gap won't be quick or easy politically. It requires consistent public investment, regulatory changes, targeted programs to encourage the adoption of capital that increases production, and labor policies that move workers into higher-value jobs instead of just having them work more hours.

That being said, there are realistic, high-impact actions that correspond with a production-first approach. First, direct government spending toward things that support the public good: digital infrastructure, skills training, and tax breaks for research and development that focus on turning ideas into commercial products rather than just basic science. Second, change company incentives so that companies, especially small and medium ones, face fewer challenges in adopting automation and cloud technologies while workers gain skills they can take with them. Third, open up sectors where competition is weak and production has stagnated, along with providing social support for workers who are affected. Fourth, welcome targeted immigration and alumni networks that bring skills where the local population can't provide them. These are difficult changes, but they also increase income more reliably than short-term boosts in spending. When the production engine starts to turn, even slightly—say, increasing total factor production growth by a few tenths of a percent each year—the combined effect on the economy and tax income over five to ten years can be large enough to ease monetary pressures without drastic tax increases.

Policy Trade-offs, Counterarguments, and a Practical Plan to Focus on Japan manufacturing and Financial management

Critics will argue that production improvements take too long and voters want relief now, so the temptation to cut taxes and push people to work longer will be too powerful to resist. However, there's a grounded and practical response. First, justify and phase in changes. Pair any small tax relief in the near term with a legally binding, time-limited production package that shifts spending from consumption subsidies to investment and training. Second, protect credibility. Announce financial targets for the medium term that are tied to production benchmarks, with automatic, rule-based adjustments that kick in when certain growth or debt levels are reached. According to a recent study, credibility helps reduce the volatility of stock returns. Third, avoid relying too much on hours. There's the simple fact that increasing hours leads to lower output once fatigue and management issues are taken into account. It's better to get more output per hour than more hours per worker. Pushing workers to simply work longer may slightly increase the economy, but it won't solve production deficits.

A practical plan might look like this:

Immediate (0–12 months): Stabilize markets by announcing a clear financial plan that links any tax changes to production milestones and commits to targeted investment.

Short run (1–3 years): Put in place regulatory and incentive changes for small and medium businesses to adopt digital technologies, expand training programs, and start opening up certain sectors.

Medium run (3–7 years): Reap the rewards in higher total factor production and economic output, enabling gradual tax adjustments that maintain growth whilst reducing deficit levels.

This isn't magic or extreme austerity. It's about doing things in the right order: invest now to grow the base, and only then adjust rates to ensure sustainability. Markets will reward credible sequencing with lower premiums, and voters will benefit from lasting wage gains rather than temporary tax relief that's offset by future cuts.

The political victory is real and provides an answer, but it's not a financial cure. Japan encounters a situation where debt is high and there's little room for error. Markets recognize this reality and remind policymakers that commitments must align with the financial statements. The right response isn't automatic tax cuts or urging people to work longer hours. It's a disciplined, production-first strategy that connects investment, regulation, and incentives to increase output per hour. This path won't be easy, but it's the only credible way to turn a sales pitch into permanent economic well-being. We should measure success not by the size of the immediate payout, but by how quickly policy increases production and grows the tax base. That's how Japan turns a winning slogan into economic security.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera (2025) Japan gov’t greenlights record $58bn defence budget amid regional tension, 26 December.

AP (2026) Prime Minister Takaichi's party wins a supermajority in Japan's lower house, 2026.

Asian Military Review (2026) Government poll shows public support for defense exports as Tokyo considers easing key restrictions, February.

Defense News (2025) Japan passes record defense budget while still playing catch-up, 16 January.

Japan Ministry of Defense (2025) Defense of Japan 2025, Tokyo: Ministry of Defense.

Ministry of Defense Japan (2023) Implementation Guidelines for the Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology, Tokyo: Government of Japan.

Nippon.com (2026) Cabinet Office survey shows record high support for strengthening Japan’s Self-Defense Forces, 28 January.

Naval News (2025) Japan approves record defense budget for fiscal year 2026, 30 December.

Reuters (2026) Why Japan’s emboldened PM won’t toy with risks of a weak yen, February.

SIPRI (2024) Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2023, Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

The Guardian (2026) Sanae Takaichi’s conservatives cement power in landslide Japan election win, February.

Xinhua / News agencies (2025) Japan’s defense budget tops record 9 trln yen for fiscal 2026, 26 December.

People’s Daily (2026) Commentary on Japan’s expansion of military exports, 12 February.