Rethinking Sustainable Healthcare Funding: Aging, Immigration, and the Limits of Cost-Sharing

Input

Modified

Aging and migration strain universal healthcare budgets Exclusion is not sustainable Smart funding reform can protect equity and stability

Europe’s public health budgets face a simple arithmetic squeeze: current health spending is now about 10% of EU GDP, yet the population aged 65+ is growing faster than the workforce that pays for it. The old-age dependency ratio has risen into the mid-30s, meaning roughly three working-age adults for every person over 65; at the same time, roughly 10% of residents in EU countries were born outside the EU by early 2025. These two facts — a bigger elderly cohort and a growing, diverse immigrant population — are not opposites but co-drivers of pressure on universal systems. They force a hard question: how can universal coverage remain both just and solvent when demographic and migratory trends change the base of contributors and claimants? This column reframes that question away from quick cuts and toward a pragmatic policy menu that preserves core solidarity while adjusting funding and incentives to protect care, not ration it.

Durable healthcare funding: why the framing matters now

The dominant policy frame treats aging and immigration as rival pressures on budgets, a zero-sum politics where benefits for one group subtract from those of another. That frame is misleading and dangerous. Framing matters because it determines the policy instruments we reach for — tax hikes, benefit cuts, tighter eligibility for newcomers — and those choices influence health outcomes and social cohesion. Reframing should start from two empirical realities. First, health spending in the EU is large and rising: current health expenditure was around 10% of GDP in 2023, with substantial variation throughout member states and continued growth in per-capita costs driven by technology and chronic care. Second, migration is not a single fiscal shock; it alters both the numerator (beneficiaries) and the denominator (contributors) in complex ways. In 2023, the EU recorded millions of new immigrants, and by 2025, roughly 10.4% of the population in EU countries were born outside the bloc. These data reveal that pressure on public finances is real, but they do not imply that the only rational policy is exclusion. The choice is among short-term frugality and long-term design: do we preserve universal access with smarter funding, or do we trim eligibility and accept higher downstream costs in emergency care, epidemic control failures, and fractured labor markets?

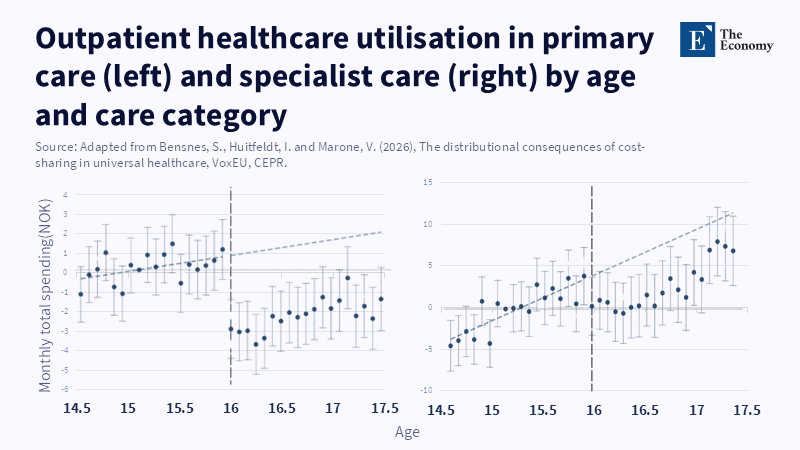

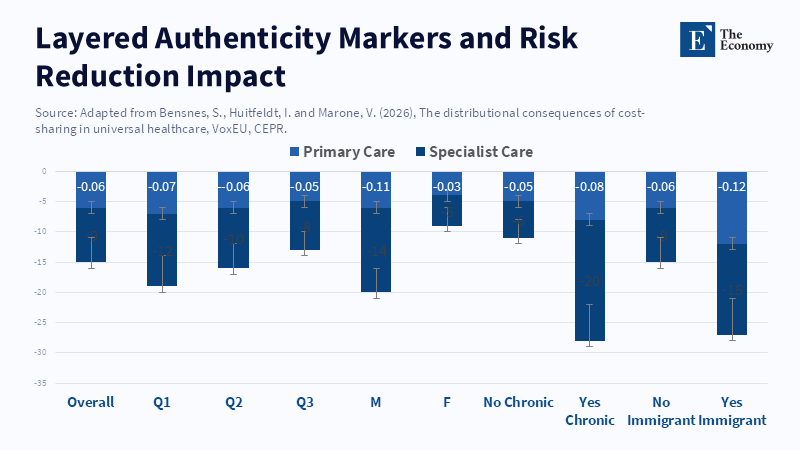

The best policy response will not rest on a single lever, such as across-the-board co-payments or blanket denial of access for undocumented migrants. Cost-sharing has a proven effect of lowering outpatient visits when prices rise, but it is blunt: it deters both low-value and necessary care. Evidence from natural experiments in universal systems shows clear discontinuities in use at the onset of co-payments; utilization falls, but the distributional consequences can be regressive and increase unmet need among the poor and chronically ill. In short, co-payments can buy short-run fiscal breathing room, but they risk longer-run harm — higher hospitalizations, avoidable morbidity, and political backlash — that ultimately undermines sustainability. Policymakers should therefore treat co-payments as a targeted tool inside a wider funding and integration strategy, not as the primary fix.

This reconsideration matters now because Europe’s fiscal room is narrowing. Defense and security spending has risen for multiple member states' governments, which encounter competing demands on public budgets. At the same time, labor markets are shifting: automation and AI will change demand for low-paid manual work, which historically absorbed many recent arrivals. The question is not whether migration should be constrained; it is how to combine migration policy, labor activation, contribution rules, and health financing so the system remains financially robust and morally defensible. Any policy that sacrifices public health goals for immediate savings is short-sighted. A pragmatic agenda must preserve core access while rebalancing the sharing of costs across incomes, contributors, and services.

Practical redesign: aligning contributions, co-payments, and integration

We need to move from a monolithic “cut or keep” debate to a modular design that aligns with instruments to policy goals. First, refine contributions to better reflect the ability to pay and attachment to the labor market. Many migrants enter formal employment and contribute more in payroll taxes than they consume, especially in younger cohorts. Regularization and rapid labor integration increase net fiscal returns and social cohesion. Second, use targeted co-payments and exemptions rather than flat fees. Cost-sharing should be calibrated to deter low-value, high-frequency visits (e.g., duplicate primary care consultations for minor ailments) while exempting preventive services, chronic disease management, and visits for children. Third, redesign provider payment incentives toward value — bundled payments, capitation, and accountable care models — to reduce low-value care and shift some cost control upstream without hurting access. Each instrument has trade-offs; combined, they can reduce waste and preserve coverage.

To ground these proposals in numbers: EU health spending equaled about 10% of GDP in 2023, and the old-age dependency ratio has climbed into the mid-30s by 2025. Immigration flows added roughly 4.3 million entrants from non-EU countries in 2023, and the stock of non-EU-born residents reached about 46.7 million by early 2025. A back-of-the-envelope calculation shows why integration matters: a 30-year-old migrant who enters employment and pays payroll taxes for a decade, obtaining considerable aged care benefits, is likely to be a net contributor over a lifetime. Conversely, excluding people from primary care pushes costs into emergency departments, where unit costs are several times higher, and outcomes are worse. These aggregate facts suggest that a policy mix emphasizing labor attachment and selective cost-sharing is more likely to be budget-friendly than blunt exclusion. Voters conflate cultural anxieties with fiscal crimping. That makes transparent, administratively simple rules essential. For example, co-payments can be phased by income bands and service types, and accompanied by real-time exemptions for low-income households and for essential public health services. Integration can be sped with work-permit pathways that tie access to social insurance to tax and contribution records rather than citizenship status alone. Finally, invest the savings from provider payment reform into primary care capacity, which reduces costly specialist and hospital use. These changes are neither radical nor anti-solidarity; they are attempts to preserve universality by making it increasingly efficient and equitable.

Anticipating critiques and rebuttals: rights, costs, and politics

The strongest critique is moral: restricting access to medical care for any group violates human rights and risks public health. That critique is valid and decisive as a boundary condition. Our proposals do not endorse denial of essential or emergency care. Instead, they aim to protect universality for core services while using fiscal design to make the system sustainable. A second critique is operational: means-testing, exemptions, and new provider payment systems require administrative capacity that many countries lack. This is true, but capacity constraints are not a reason to avoid reform; they are a reason to sequence it sensibly — start with pilot programs, improve data systems, and scale what works. Third, some will argue that migrants are a fiscal drain and that cuttinbenefits are thes is the simplest solution. The data do not uniformly support that claim: younger migrants often contribute more in payroll taxes than they draw in services in their first two decades, and regularization further increases their net contribution. According to a recent study, implementing sweeping exclusions could lead to poorer public health outcomes and may also result in lower revenue over time, especially since declines in smoking and increases in quitting have been less significant among people with moderate and low incomes.

Another expected rebuttal: targeted co-payments hurt the poor and the elderly more. Again, that is a risk. But it is a risk that can be managed with design: exemptions for low-income households, sliding scales, and free preventive care can blunt regressive effects. Empirical work shows that when co-payments are paired with exemptions and strong primary care, utilization falls primarily for low-value outpatient visits, while essential care is preserved. The alternative — blanket universal cuts — has its own regressivity: higher emergency use, worse chronic disease control, and program instability. A final political critique is that voters will punish governments that appear to “favor migrants.” The right answer is transparency: show how integration raises net fiscal returns, publish clear rules tying benefits to contributions (or vulnerability), and protect universal access for children and essential public-health services. Fiscal prudence can and should be communicated as a way to protect, not erode, universal care.

The arithmetic facing European welfare states is stark but not insoluble. Aging and migration change the shape of demand and the composition of contributors, but they do not force a choice between universal care and fiscal sanity. The policy path that retains both is mixed: accelerate labor integration and formalization to expand the contributor base; move provider payments toward value to curb waste; and use targeted co-payments with strong exemptions to deter low-value use without shutting out necessary care. Above all, protect necessary services and public health. This is not a call for austerity disguised as prudence; it is an argument for institutional realism. By redesigning how we fund care, not who gets it, we can keep universality intact — and make the system fairer, more efficient, and politically sustainable for future generations

.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Bensnes, S., Huitfeldt, I. and Marone, V. (2026) ‘The distributional consequences of cost-sharing in universal healthcare’, VoxEU Column, Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).

European Commission, Eurostat (2024) Healthcare expenditure statistics — overview. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission, Eurostat (2024) Population structure and ageing. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission, Eurostat (2025) Migration and migrant population statistics. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Nguyen, V.K., Papamichail, A., Papanicolas, I. and Cylus, J. (2023) ‘Financial protection and unmet healthcare needs in Europe: trends and policy implications’, The Lancet Regional Health — Europe, 33, 100741. (Example paper — authors for context in article.)

Stevenson, K. (2024) Universal health coverage for undocumented migrants in Europe: challenges and evidence, The Lancet Regional Health — Europe.

World Health Organization (2023) Can people afford to pay for health care? Evidence on financial protection in 40 countries in Europe. Geneva: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

OECD (2023) Health at a glance 2023: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

van Doorslaer, E., Masseria, C., Koolman, X. and OECD Health Equity Research Group (2006) ‘Inequalities in access to medical care by income in developed countries’, Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174(2), pp.177–183.

Comment