Sky Dominion: Why “low earth orbit control” is the next geopolitical fault line

Input

Modified

Low earth orbit control is becoming a new arena of geopolitical power Satellite constellations are dual-use tools Without coordinated governance, orbital dominance could reshape global security and civilian life

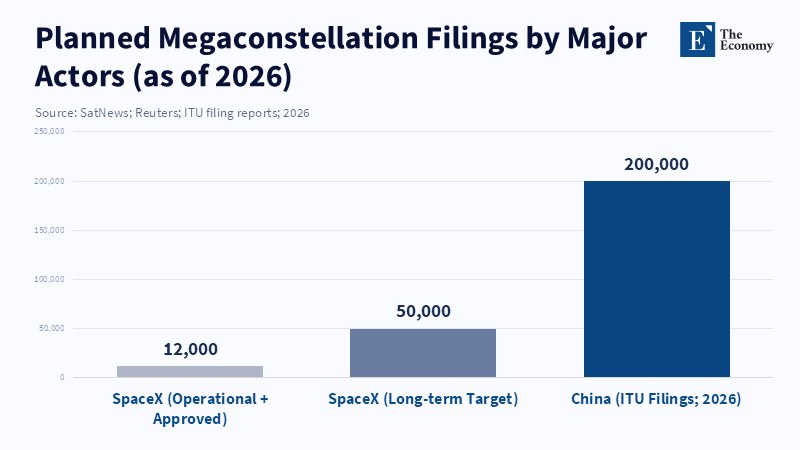

A single statistic nails the problem: in late 2025, China applied to operate nearly 200,000 satellite slots while private actors and regulators are already approving tens of thousands more; together, those filings offer an orbital density the planet has never seen and an observational reach that can turn ordinary broadband networks into instruments of global oversight. Low Earth orbit control is no longer a metaphor. It is a technical and political competition over who can observe, communicate with, and — crucially — influence life on the ground. The recent constellations promise cheaper, faster internet, but they also embed tiny, networked sensors and steerable radios into orbital layers that cross borders without consent. The result: infrastructure that is simultaneously civilian, commercial, and eminently usable for surveillance, command, and competitive coercion. That duality changes what educators, administrators, and policy-makers must now imagine and do.

The stakes of low earth orbit control

Reframing the debate means treating LEO not as a neutral commons but as infrastructure that allocates observational and communications power. The standard story about satellite internet has been economic: greater connectivity, market competition, and lower latency. That story is true in part. Yet when we reframe the argument around low earth orbit control, we see a different political fact: the entities that dominate orbital layers also gain persistent, worldwide sensing and signaling advantages. Those capabilities shift bargaining power across states and corporations. They shape who can monitor supply chains, who can maintain communications under conflict or disaster, and who can project influence without basing forces on foreign soil. The asymmetry matters for education systems because learning, assessment, and campus security increasingly depend on networked systems whose availability and privacy depend on space-based infrastructure decisions made far from classrooms.

This reconsideration is urgent because filings and approvals—commercial requests to national regulators and to the ITU—are outpacing governance. Where once orbital governance relied on Cold War-era treaties and diplomatic norms, today hundreds of thousands of small satellites can be launched by firms or state-backed consortia. These units are cheaper, more maneuverable, and capable of carrying higher-resolution optical and radar sensors. The technical capability to observe at sub-meter scales from compact platforms has moved from elite national programmes into the commercial mainstream. When that observation is coupled with global communications relays, the satellite becomes both camera and pipe. Policymakers thus face a compound problem: regulating spectrum and collisions, yes — but also preventing an unchecked consolidation of observational advantage in the hands of actors with mixed commercial and security aims.

How dual-use constellations reshape power

The technical details are blunt instruments of power. Small optics and synthetic-aperture radar now offer sub-meter imagery. Constellation operators pair those sensors with global relay networks and cloud processing. That combination multiplies intelligence value. A satellite with a small camera is not simply a comms node; it can collect imagery, cue other sensors, and feed machine learning systems that detect movement, shipments, or gatherings in near-real time. Those functions were once exceptional. They are fast becoming routine.

Commercial deployments already shape crises. In recent years, satellite internet and imagery have been used to support emergency response, track refugee flows, and maintain lines of communication when ground infrastructure failed. At the same time, states and firms have repurposed the same systems for surveillance, jamming, and influence operations. The dual-use nature of LEO assets creates brittle dependencies. Schools, universities, and education services that rely on satellite links for distance education could find access cut off or throttled by states in a geopolitical dispute. They could also see their data routed through operators with ties to competing governments. These are not hypothetical vulnerabilities; they follow directly from the concentration of orbital capability.

Economic forces amplify governance gaps. Major private firms pursue scale to cut per-user costs; states pursue national champions to secure sovereign access. The outcome is a market that rewards mass deployment. Hence, filings for very large constellations. Where deployment precedes robust rules, the actors who reach physical presence first gain durable leverage. That leverage looks like bargaining chips in trade negotiations, backstops for military operations, or influence over global information flows. Education systems become collateral in such circumstances. Decisions about platform choice, procurement, and curriculum that assume neutral connectivity are now political choices about exposure to the control wielded by orbital operators.

Policy pathways to govern low earth orbit control

If we accept that low-earth-orbit control is a policy problem, the question becomes: what governance mixes reduce risk while preserving benefits? First, a tighter set of operating conditions must accompany spectrum and orbital authorizations. Regulators should attach commitments regarding transparency, data-use limits, and multi-party access to fundamental telemetry. Authorizations that only consider frequency and collision hazard are insufficient. Firms and states that grant slots for observation and global relay should be required to disclose sensor capabilities, acceptable use policies, and access controls. That disclosure is not a panacea, and it raises the political cost of weaponizing ostensibly civilian networks.

Second, coalition-based resilience can blunt the leverage of any single actor. Education networks, research institutions, and municipal services should be able to route traffic across several constellations and terrestrial links by default. Procurement standards should favor multi-provider architectures and open interconnection. From a policy standpoint, resilience requirements can be incorporated into grant programs and public education infrastructure purchasing agreements. Doing so reduces the single-source dependence that an adversary could exploit. It also creates market pressure for interoperable standards and for actors to compete on reliability and privacy, rather than mere scale.

Third, we need export and use restrictions that reflect capability, not ideology. Current controls often focus on platform exports of large satellites or missiles. They do not capture the distributed, commercial architecture of modern constellations. A refined regime should control the export of integrated systems that combine high-resolution sensing with continuous global relay in ways that materially increase surveillance reach. These rules must be multilaterally negotiated to avoid simple relabeling by vendors. According to a report from the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs, export controls on satellite technology can affect cross-border cooperation and require a balanced approach. To address concerns regarding surveillance and misuse, policymakers should pair these controls with incentives for open, privacy-focused services and establish international mechanisms to resolve disputes. The report also highlights the importance of funding oversight by academic and civic organizations. Universities and civil society can provide independent audits of orbital operators’ claims and usage. Public-interest labs can test claims about image resolution, data retention, and cross-border data flows. This work should be supported by research grants tied to transparency requirements and by regulatory mandates requiring that operator metadata be made available to accredited auditors. Accountability reduces the opacity that allows mixed-use functions to masquerade as benign.

Anticipating objections

Skeptics will argue that tighter rules and procurement standards slow innovation. They will note that satellite internet has brought connectivity to remote classrooms and that over-regulation risks throttling those gains. That is true; regulation must be calibrated. The goal is not to stop deployment, but to shape it so that educational and civic benefits are not hostage to emergent monopolies or to great-power competition. Simple, enforceable transparency and sturdiness conditions entail modest costs compared with the social cost of systemic dependency.

Others will point out the difficulty of a multilateral agreement. Great-power rivalry makes binding commitments hard. But governance can begin with pragmatic, functional coalitions: regional blocs, multinational research consortia, and procurement unions. When education ministries and research universities coalesce around standards for cross-provider redundancy and open interfaces, they create de facto norms. Markets follow. According to a report from NAM, procurement requirements that focus on system-wide interoperability rather than buying individual products with proprietary interfaces can quickly drive outcomes in networked industries. A somewhat more nuanced counterargument suggests that technological solutions, such as encryption, edge computing, and data limitation, tackle privacy and control concerns. They help, but they cannot remove the asymmetry of observation. If one actor controls a dense orbital layer, they can still see temporal patterns, signal metadata, and behavioural correlates that survive encryption. Policy must therefore combine technical measures with institutional arrangements that limit control and enable contestability.

Low Earth orbit control is a contested infrastructure that will shape the next decade of pedagogy and public life. The field of education cannot treat connectivity as merely a commercial convenience. Administrators must demand diversified orbital access and insert resilience clauses into procurement. Authorities must require basic transparency from anyone granted the ability to operate global sensing and relay architectures. Regulators should link spectrum and orbital authorizations to verifiable commitments on data use, sensor disclosure, and third-party audits. Internationally, coalitions of education and research institutions can set procurement and interoperability standards that create safer markets. These steps preserve the enormous promise of satellite-enabled learning while making it far harder for any single actor—state or corporate—to convert orbital presence into unchecked observational power. The orbit above our heads is becoming an instrument of governance on Earth. If we fail to shape that governance now, we teach the next generation under an infrastructure we do not control.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

D’Errico, M. (2025) ‘Evolution of spaceborne SAR missions in Earth orbit’, Remote Sensing, 17(2), pp. 1–24.

MERICS (Mercator Institute for China Studies) (2025) Orbital geopolitics: China’s dual-use space internet strategy. Berlin: MERICS.

Pixalytics Ltd (2025) ‘How many satellites are orbiting the Earth in 2025?’, Pixalytics Industry Report, January.

Reuters Staff (2026) ‘FCC approves SpaceX plan to deploy additional Starlink satellites’, Reuters, January.

SatNews Editors (2026) ‘As SpaceX targets 50,000 Starlink satellites, China files for 200,000-unit mega-constellation’, SatNews, 12 January.

Taylor, M. (2026) ‘Starlink, China and the governance of low Earth orbit’, East Asia Forum, 19 February.

Union of Concerned Scientists (2024) UCS Satellite Database. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists.

Comment