Strategic Containment and Strategic Innovation: Rethinking the US-China AI Competition

Input

Modified

The US-China AI competition is shifting from scale to system control China caught up through centralization; the US is reshaping access and alliances Education will decide who sets the next AI standards

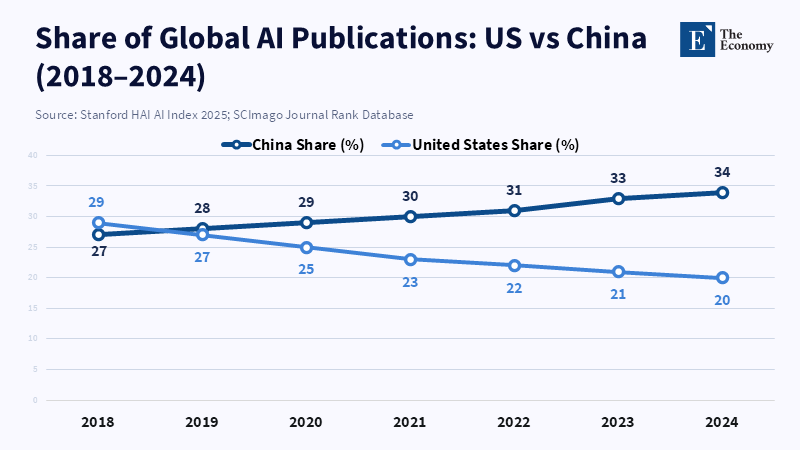

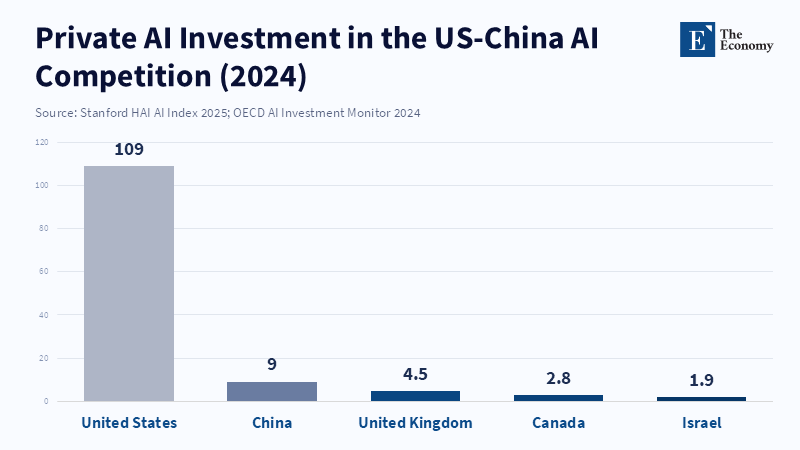

In 2024, the United States saw approximately $109 billion invested in private AI ventures, while China attracted around $9 billion. This tenfold difference indicates American dominance, but the amount of money involved doesn't guarantee long-term success. This financial gap is the backdrop to the AI rivalry between the U.S. and China, but it's not just a simple matter of who spends more. China has been able to quickly close performance gaps by using government resources and its own internal markets. In the next five years, the focus will shift from simple catching up to strategic footing: which country sets the technical rules, which forms alliances, and which may limit access to parts of the global AI network. This is important for educators and officials because the selections we make today—regarding what we teach, who has access to research, and how we control exports—will set us on paths that either create more chances for everyone or solidify existing advantages. If we only look at the competition as a matter of numbers, we'll miss the changes happening in education, research, and regional standards due to political influence.

Seeing the US-China AI Competition Differently: From Just Catching Up to Planned Exclusion

The common story is that China is catching up to the U.S. by spending a lot and using government control. While there's truth to this, it doesn't give the full story. It assumes the competition is merely reaching the identical technical level on a level playing field. A better way to see it is as two connected battles: one within the scientific and business communities, and the other involving diplomacy, trade rules, and the establishment of international standards. The first battle is won by having a lot of computing power, talent, and investment, while the second depends on controlling the network—deciding who gets access to which tools, who can buy certain computer chips, and what standards will guide how AI is used globally. Seeing the US-China AI competition this way shows the choices facing schools and universities: they not only produce talent but also serve as connection points in international research networks, which can be redirected or limited by policy.

This is happening now. According to a recent report, the United States has taken active steps to shape the global AI landscape by implementing new export controls that restrict China's access to and development of advanced computing and microchip technologies. These measures create new challenges for some research efforts and technology supply chains. For educators, this means they have two jobs: to keep training people in the country while also developing courses along with partnerships that can handle potential breaks in international relations. Students need to learn technical skills and understand how institutions operate so they can work across various, possibly separate, systems. According to research published by Ritwik Gupta and colleagues, if educational programs do not adapt to shifting export controls on technology, degrees from those programs may be valuable only within limited sectors and may not translate well into opportunities elsewhere. The study also notes that redirecting focus to network control changes how university leaders set their priorities. Grants, partnerships, and access to cloud computing become strategic resources. A university that relies on foreign suppliers or a single company's tools might face sudden constraints if export restrictions or tariffs are imposed. This new way of thinking asks institutions to check their dependencies, find different suppliers for hardware and cloud computing, and create courses that teach students how to rebuild systems using alternative tools. This is a big task, but it's important if the US-China AI competition becomes about who has access, not just who performs better.

This changed view also changes how we measure success. Traditional measures like the number of research papers, startups, or total funding are still important, but so are network-related measures: which universities are trusted collaborators, who is approved to use advanced chips, and which institutions are included in important discussions about regulations. For educators and leaders in higher education, the goal is to connect building skills with the development of resilience. We should train more engineers, but also train administrators, procurement staff, and scholars who can understand export rules and international politics. This is how institutions can ensure research continues even as the rules of the game change.

What to Expect in the Next Five Years of the US-China AI Competition

Expect a change in strategy. At first, China used government resources to catch up by quickly hiring talent, expanding its cloud computing capabilities, and investing in specific industries. The next step will involve intentional exclusion and the creation of separate systems. Basically, the United States and its allies will try to maintain exclusive access to the most advanced technology while promoting solutions that align with their governing principles. This means more targeted controls on high-end computer chips, licensing with conditions, and export plans that favor purchases from allies. The policy approach is already shifting from simply preventing certain actions to actively molding the situation.

These actions will have real effects on classrooms and labs. Companies and labs that used to buy powerful computing resources from anywhere in the world might find their access delayed or restricted. This will limit the scope of experiments for some and push others to focus on software improvements, efficient algorithms, and simpler models. In other words, limited access to hardware will encourage smarter software and teaching that concentrates on achieving more with less. Course designers ought to prioritize methods that use less computing power: efficient designs, fine-tuning that requires fewer adjustments, and using synthetic data. These are good teaching practices because they increase access and teach engineers to be mindful of resources.

Politically, the US-China AI competition will create more ambiguous situations than outright bans. Policymakers will likely use licensing on a case-by-case basis to reduce economic backlash while still impacting outcomes. Companies will respond by varying their supply chains and managing political risks. For education leaders, this means negotiating new partnerships, demanding clear licensing terms, and pushing funders to support computing resources for research that benefits the public but might be affected through decoupling. Universities with international students will also need explicit communication plans; students who expect easy access to tools must understand how international politics can impact research timelines.

Economic elements will also change. Lower-cost Chinese models and providers will compete in market areas where high performance is less critical. According to an analysis of recent trends, lower-priced Chinese AI options are increasingly competing with premium Western services, prompting Western companies to focus more on trust, safety, and seamless integration rather than just price. For educators, this means helping students to assess AI models for suitability and reliability, rather than depending solely on benchmark scores, and designing course activities that reflect these priorities. This program trains professionals to integrate models in industries where compliance and source are more important than low cost. This prepares graduates for a market in which trust is a key factor, not simply an afterthought.

Policy Priorities: Education, Infrastructure, and Diplomatic Strength in the US-China AI Competition

If the next five years focus on exclusion and building alliances, policy needs to address three areas: workforce, infrastructure, and international relations. For the workforce, we need more targeted technical programs that reach both college students and experienced professionals. But increasing the number of people trained shouldn't mean lowering standards. Training should be modular and focus on how software and hardware work together, as well as the legal aspects of export restrictions. Funders should support computing access for research that benefits the public to prevent a gap between elite labs and other academic institutions.

In terms of infrastructure, governments should invest in distributed computing centers and national cloud computing credits to keep public research competitive without relying on unstable supply chains. The goal isn't to have the fastest computing power everywhere but to ensure predictable resources for reliable research and education. This reduces the risk that sudden export changes will halt entire research projects. It additionally promotes a better balance: innovation driven by clever algorithms and efficient systems, rather than just raw computing power.

Worldwide partnership is the third key area. The US-China AI competition will be won or lost in standards organizations, purchasing practices among allies, and rules about data sharing. Educational institutions are both participants and stakeholders here. They can lead by providing clear rules for data use, hosting international research groups with clear access guidelines, and providing technical advice to allied governments, including the creation of export or interoperability rules. Universities that actively participate in these discussions will help shape the rules that determine whether their graduates' skills are useful internationally.

Thinking ahead about potential criticisms helps improve the policy mix. One likely concern is that export controls and alliance strategies will lead to a separation that harms international science. This is a valid concern. But policy can be designed to be selective: target only the specific technologies that enable unrestricted copying of state-of-the-art models, while keeping general research collaboration open. Another criticism is that these actions will push China to become more self-sufficient. While it's true that China will invest more in domestic chips and innovation, this simply strengthens the argument for U.S. policies that make allied systems more attractive and compatible for other countries.

A final concern is whether universities and schools can adjust rapidly enough. The answer is to start small and stay focused. Begin by checking dependencies, securing alternative suppliers, and creating computing resources for work that benefits the public. Then, update core courses to teach efficiency and governance alongside algorithms. These are practical steps that move institutions from vulnerability to resilience.

In conclusion, the headline about $109 billion versus $9 billion only tells part of the story of the US-China AI competition. The upcoming competition will be as much about access, rules, and alliances as about money. For educators, administrators, and policymakers, the challenge isn't just who writes the best paper this year, but who builds systems that ensure learning remains transferable, research remains resilient, and students remain employable in a disjointed world. It's important to act now to check dependencies, update courses to concentrate on efficiency and governance, and provide public computing resources for research that serves the common good. According to OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, relying solely on export controls will not be effective at limiting China's progress in artificial intelligence. Moving forward, it is fundamental to approach the next five years as both an administrative and a technical challenge, focusing on maintaining open scholarly exchange and supporting civilian uses of AI, while also strengthening institutions to adapt if the international competitive environment changes.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Economy or its affiliates.

References

Allen, G.C. (2025) America’s AI Action Plan. Washington, DC: The White House.

Allen, G.C. (2025) Promoting the Export of the American AI Technology Stack. Washington, DC: The White House.

Congressional Research Service (2025) U.S. Export Controls and China: Advanced Semiconductors (R48642). Washington, DC: CRS.

Cao, C. (2025) ‘Is an AI price war about to begin?’, Financial Times.

Edelman, R.D., Fu, D., Hass, R., Kim, P.M., Lin, Y., Ma, Y., O’Hanlon, M.E., Sisson, M.W., Tabassi, E. and Turner Lee, N. (2025) ‘How will AI influence U.S.–China relations in the next five years?’, Brookings Institution.

Friedberg, A. (2025) ‘A clear winner of U.S.–China competition is unlikely’, Inkstick Media.

Holmes, F. (2025) ‘Why the U.S.–China AI arms race is entering a critical new phase’, Seeking Alpha.

Kahn, J. and Mozur, P. (2025) ‘The AI race between the U.S. and China’, Time Magazine.

Ostrovsky, N. (2026) ‘Where is the U.S.–China AI race heading in 2026?’, Deutsche Welle.

Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (2025) AI Index Report 2025. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

Comment